-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hideya Onishi, Atsushi Higa, Mayu Tasaki, Yuki Inaoka, Aya Okuda, Yoshio Miki, Yasuaki Tsuchida, Hitoshi Hino, Masahiko Kawamoto, Shinya Ueda, Nobuyuki Takai, Koshiro Ando, Michiko Tani, Nobuyuki Tani, Tomoki Ito, Hisakazu Yamagishi, Yusuke Nakamura, Kohji Tani, Neoantigen dendritic cell vaccination combined with conventional chemotherapy for a patient with advanced transverse colon cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1030, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1030

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Over the past decade, neoantigen dendritic cell (DC) vaccination has emerged as a promising personalized cancer immunotherapy based on genomic analysis. To further assess the clinical utility of this approach, additional data on the efficacy of neoantigen DC vaccination are needed. A 65-year-old male patient underwent curative surgical resection for pStage IIIB transverse colon cancer, followed by adjuvant DC vaccination combined with conventional chemotherapy for 6 months postoperatively. The neoantigen DC vaccination effectively reduced elevated carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Moreover, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) isolated from the patient’s peripheral blood demonstrated specific recognition of the neoantigen peptides. Our findings suggest that CTLs recognizing tumor-specific neoantigens may play an important role in immune surveillance against cancer recurrence. The patient remains alive and disease-free 16 months after surgery.

Introduction

In Japan, colon cancer represents the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men and the leading cause among women. In terms of incidence, it ranks second among all malignant tumors in both sexes [1]. Although the number of chemotherapeutic and molecular-targeting agents available for colon cancer has increased, treatment options remain insufficient, and further strategies to improve patient outcomes are required.

Since the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy has been recognized as the fourth major therapeutic modality following surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Dendritic cells (DCs) were first identified as professional antigen-presenting cells by Steinman in 1990 [2]. The induction of DCs from peripheral blood monocytes was first reported in 1994 [3], and DC-based cancer vaccination has since been developed as a form of antigen-specific immunotherapy. Over the past two decades, DC vaccination has demonstrated some extent of efficacy against various solid tumors [4–6], primarily through the use of shared tumor-associated antigens (oncoantigens).

The concept of neoantigens generated by genetic alterations in cancer cells was proposed by Schreiber et al. in 1995 [7]. Neoantigens, peptides derived from tumor-specific somatic mutations, are predicted through genomic analysis of resected tumor specimens, on the basis of their expression in cancer cells as well as their affinity to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules of individual patients. Compared with DC vaccination using oncoantigens, neoantigen-loaded DC vaccination is expected to offer greater tumor specificity, safety, and therapeutic efficacy. Given that neoantigen-based immunotherapy is still in its early stages, the accumulation of clinical evidence on the efficacy of neoantigen DC vaccination is anticipated in the coming years.

Here, we report a case of advanced colon cancer successfully treated with neoantigen DC vaccination combined with conventional chemotherapy. The patient remains alive and free of disease recurrence 16 months after surgery.

Case presentation

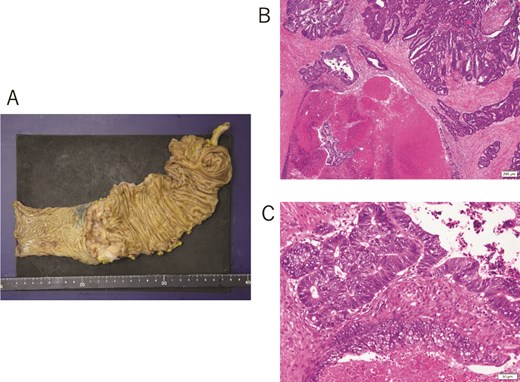

A 65-year-old male patient underwent colonoscopy in April 2024 due to positive results in a stool occult blood test and was diagnosed with a neoplastic lesion and high-grade stenosis in the transverse colon. Pathological examination of a biopsy sample revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The preoperative blood examinations, including those for tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), showed results within normal range. No metastatic lesions were observed in the distant organs. The patient underwent curative surgical resection with robot-assisted laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. The resected specimen showed a fine-bordered tumor lesion with an ulceration (diameter, 65 × 43 mm) in the transverse colon (Fig. 1A). Histological examination revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with infiltration into the subserosal layer and metastasis to the lymph nodes: pT3, pN1b, cM0, and pStage IIIB in Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classification (Fig. 1B and C).

(A) Surgical resected specimen showing a tumor lesion with clear borders and ulceration and a diameter of 65 × 43 mm in the transverse colon. (B, C) Histological findings showing moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma.

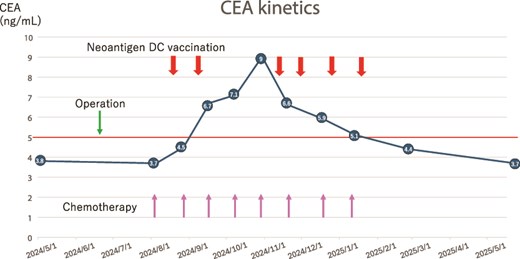

After the surgery, the patient underwent immunotherapy, neoantigen DC vaccination using six class I neoantigen peptides, along with chemotherapy, which involved intravenous oxaliplatin administration on Day 1 and oral capecitabine administration from Day 1 to Day 14 (XELOX therapy). The quality of the DCs was assessed using a light microscope and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) immediately before administration each time (Fig. 2). The patient received eight courses of chemotherapy and six courses of neoantigen DC vaccination. The therapy schedule and the findings for tumor marker kinetics are shown in Fig. 3. The protocol for neoantigen DC vaccination is described in detail in the Methods section. The elevated CEA levels had decreased significantly during the third to sixth neoantigen DC vaccinations (Fig. 3). To monitor minimal residual disease (MRD) following surgery, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was assessed using a liquid biopsy in January 2025. Somatic mutations in 50 cancer-associated genes were analyzed (Supplementary Table S1). Three copies of an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation (A289V) were detected. This mutation was not detected in the neoantigen analysis; therefore, we hypothesized that it appeared during the postoperative therapy period. However, no obvious recurrence site was detected on CT in June 2025, and the CEA levels were within normal limits on August 22. The patient is currently alive 1 year and 4 months after the surgery. Written informed consent for the publication of this report was obtained from the patient.

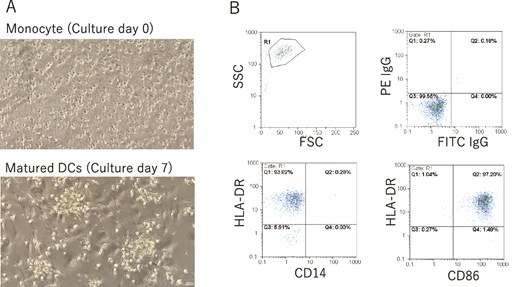

(A) Pictures of monocyte (culture Day 0) and matured DCs (culture Day 7) by light microscope. Magnification is 100×. (B) Surface markers of CD14, CD86, and HLA-DR of neoantigen-loaded DCs were investigated by FACS every time right before the administration. Administrated DCs showed CD14−CD86+HLA-DR+ phenotype.

Therapy schedule and tumor marker kinetics. The thick arrows show neoantigen DC vaccine therapy. Thin arrows show oxaliplatin administration.

Methods

DC vaccination

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from fresh blood samples. The PBMCs were diluted with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS; Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) and cultured in T75 flasks (Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan) in AIM-V medium (Thermo Fisher, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min. After removing floating cells and washing them with AIM-V medium, adherent cells were cultured in AIM-V medium containing 5% autologous serum, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Miltenyi Biotec, GladBach, Germany), and interleukin (IL)-4 (Miltenyi Biotec). On Day 6, immature DCs were pulsed with OK-432 (Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) and prostaglandin E2 (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corp., Osaka, Japan) to induce mature DCs. Mature DCs were pulsed with 16.7 μg/ml of neoantigen in a 6-well plate (BD Falcon) using AIM-V medium for 2 h, washed three times in saline, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of saline in a 1-ml disposable syringe. Contamination by Escherichia coli, fungi, and mycoplasma was checked by blood culture (BML, Tokyo, Japan), an Endospecy ES-50M kit (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan), and MycoAlert (Lonza, Tokyo, Japan). The neoantigen-pulsed DCs were immediately administered to the patient through intranodal injection under ultrasound guidance by a skilled physician. The patient tolerated the vaccination therapy well without any treatment-associated adverse events except low fever.

Flow cytometry analysis

Phenotypic DC changes were monitored using light microscopy and flow cytometry. The cell-surface marker phenotype of monocyte-derived mature DCs was determined by single-color fluorescence analysis using Cyflow (Sysmex Partec GMBH, Goerlitz, Germany). Cells (2 × 105) were resuspended in 50 μl of D-PBS and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with 10 μl of the monoclonal antibodies specific for human Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC) Immunoglobulin (IgG), Cluster of Differentiation (CD)14, and CD86 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), and Phycoerythrin (PE) IgG and Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-DR (Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). After incubation, the cells were washed twice and resuspended in 500 μl of D-PBS. Cellular fluorescence was analyzed using FloMax (Sysmex Partec GMBH).

Prediction of potential neoantigens

Whole-exome sequencing was performed as described previously [8]. Using an AllPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen), genomic DNA was extracted from the patient’s tumor cells obtained from the primary surgical tissue, whereas normal control genomic DNA was extracted from the patient’s PBMCs. Whole-exome libraries were prepared from genomic DNA using the SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The prepared whole-exome libraries were sequenced using 100-bp paired-end reads on a HiSeq sequencer (Illumina). The selected neoantigen sequences are listed in Table 1.

| Neoantigen peptide . | Normal peptide . | Tumor sample . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name . | Replacement of amino acid . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Expression level . | |

| 1 | PPP4R1 | R104W | WPSIPYAF | 6 | RPSIPYAF | 69 | 13 |

| 2 | TMEM180 | D135E | CLYEGFLTLV | 9 | CLYDGFLTLV | 7 | 29 |

| 3 | PLIN3 | D222N | SLDGFNVASV | 11 | SLDGFDVASV | 11 | 101 |

| 4 | GPRC5A | S195F | MALTFLMF | 15 | MALTFLMS | 3499 | 196 |

| 5 | CEP95 | P262R | AAIRLHPPY | 20 | AAIPLHPPY | 9 | 129 |

| 6 | SLC12A7 | R405C | AEESCASAL | 49 | AEESRASAL | 250 | 40 |

| Neoantigen peptide . | Normal peptide . | Tumor sample . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name . | Replacement of amino acid . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Expression level . | |

| 1 | PPP4R1 | R104W | WPSIPYAF | 6 | RPSIPYAF | 69 | 13 |

| 2 | TMEM180 | D135E | CLYEGFLTLV | 9 | CLYDGFLTLV | 7 | 29 |

| 3 | PLIN3 | D222N | SLDGFNVASV | 11 | SLDGFDVASV | 11 | 101 |

| 4 | GPRC5A | S195F | MALTFLMF | 15 | MALTFLMS | 3499 | 196 |

| 5 | CEP95 | P262R | AAIRLHPPY | 20 | AAIPLHPPY | 9 | 129 |

| 6 | SLC12A7 | R405C | AEESCASAL | 49 | AEESRASAL | 250 | 40 |

aThe bold character shows the mutated sequence.

| Neoantigen peptide . | Normal peptide . | Tumor sample . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name . | Replacement of amino acid . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Expression level . | |

| 1 | PPP4R1 | R104W | WPSIPYAF | 6 | RPSIPYAF | 69 | 13 |

| 2 | TMEM180 | D135E | CLYEGFLTLV | 9 | CLYDGFLTLV | 7 | 29 |

| 3 | PLIN3 | D222N | SLDGFNVASV | 11 | SLDGFDVASV | 11 | 101 |

| 4 | GPRC5A | S195F | MALTFLMF | 15 | MALTFLMS | 3499 | 196 |

| 5 | CEP95 | P262R | AAIRLHPPY | 20 | AAIPLHPPY | 9 | 129 |

| 6 | SLC12A7 | R405C | AEESCASAL | 49 | AEESRASAL | 250 | 40 |

| Neoantigen peptide . | Normal peptide . | Tumor sample . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name . | Replacement of amino acid . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Sequence of amino acid . | Affinity of HLA (μM) . | Expression level . | |

| 1 | PPP4R1 | R104W | WPSIPYAF | 6 | RPSIPYAF | 69 | 13 |

| 2 | TMEM180 | D135E | CLYEGFLTLV | 9 | CLYDGFLTLV | 7 | 29 |

| 3 | PLIN3 | D222N | SLDGFNVASV | 11 | SLDGFDVASV | 11 | 101 |

| 4 | GPRC5A | S195F | MALTFLMF | 15 | MALTFLMS | 3499 | 196 |

| 5 | CEP95 | P262R | AAIRLHPPY | 20 | AAIPLHPPY | 9 | 129 |

| 6 | SLC12A7 | R405C | AEESCASAL | 49 | AEESRASAL | 250 | 40 |

aThe bold character shows the mutated sequence.

Mutation calling [9] was performed using the following parameters: (i) base quality ≥ 15; (ii) sequence depth ≥ 10; (iii) variant depth ≥ 4; (iv) variant frequency in the tumor ≥ 10%; (v) variant frequency in normal samples < 2%; and (vi) Fisher’s P-value < .05. The tumor mutation burden (TMB) was calculated as the number of coding mutations per megabase.

The HLA class I genotypes of these patients were predicted from the normal whole-exome sequencing data using the OptiType algorithm [10]. Neoantigens were predicted for each non-synonymous variant (SNV), and the binding affinities of all possible 8–11-mer peptides for HLA class I molecules (HLA-A and HLA-B) were examined using NetMHC v3.4 software and NetMHCpanv2.8, as described previously [11]. Candidate neoantigen peptides with a predicted binding affinity [half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)] ≤ 50 nM were selected for further analyses.

ELISpot assay

The ELISpot assay was performed using a Human IFN-γ ELISpot PLUS kit (MABTECH, Cincinnati, OH, USA) with a modified version of the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 96-well plates with nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Molshelm, France) precoated with primary anti-interferon (IFN)-γ antibody were pretreated with AIM-V medium containing 5% autologous serum at 4°C overnight. A total of 1.7 × 105 autologous lymphocytes and each neoantigen peptide (at 50–100 μg/ml) were added to each well, followed by incubation for 16 h. The plate was washed three times with PBS, and a secondary antibody was added to each well, followed by incubation for 2 h. The plates were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and stained with TNB (MABTECH). Specific spots were quantitatively defined by positivity for the neoantigen-specific T-cell response. Spots were counted under a microscope.

Discussion

Chemotherapy agents include two types of drugs: anticancer drugs of the cell-killing type, which primarily function by causing DNA injury, and molecular targeting agents that target several receptors expressed on the cancer surface and block the signaling pathway. DC vaccination mainly involves the activation of lymphocytes by binding of T-cell and DC HLA receptors. The activated lymphocytes attack cancers in an antigen-specific manner. Therefore, immunotherapy, including DC vaccination, is desirable for the combination therapy of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy in the context of the possibility of attacking cancer cells with diverse mechanisms. In our patient, neoantigen DC vaccination was considered successful in combination with conventional chemotherapy.

Interestingly, Fig. 3 presents one aspect of the effectiveness of neoantigen DC vaccination. In our regimen, neoantigen DC vaccination was supposed to be performed 2 weeks after oxaliplatin administration; however, neoantigen DC vaccination could not be performed twice during the period from early September to early November. During this period, the patient’s blood CEA levels increased beyond the normal value. However, the blood CEA level rapidly normalized after resumption of neoantigen DC vaccination. Because both the white blood cell number and C-reactive protein value were within normal limits in this period and the possibility of an inflammatory condition was unlikely, we think that the elevation of the CEA value may be a sign of recurrence. CEA levels were within the normal range before surgery, but increased postoperatively, which may suggest the selective proliferation of CEA-producing cancer cells. The detection of an EGFR mutation in plasma ctDNA after treatment may also indicate a phenotypic change in the tumor. However, we speculate that the treatment was effective, as the CEA-producing cancer cells that increased also contained the neoantigens we selected. Since there are no preoperative data regarding the EGFR mutation in a blood sample, careful follow-up will be necessary to evaluate its significance.

We cannot completely exclude the possibility that the chemotherapy was effective. Although chemotherapy was administered regularly during this period, the CEA level increased when the neoantigen DC vaccination was discontinued. However, when the neoantigen DC vaccination was resumed, the CEA level decreased markedly. Therefore, we think that neoantigen DC vaccination was effective in our case. This result also indicates that neoantigen DC vaccination requires more than three rounds of therapy. We believe that the patient may have shown relapse if he had not received the neoantigen DC vaccination.

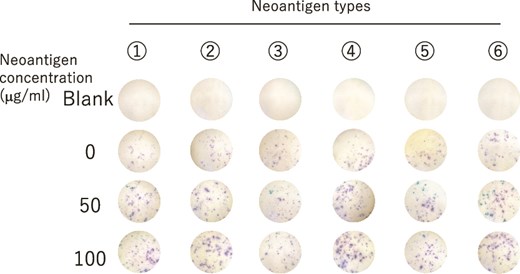

Because lymphocytes secrete IFN-γ when they are activated, we investigated IFN-γ secretion by lymphocytes using the IFN-γ ELISpot kit with the lymphocytes obtained on 10 January 2025 (Fig. 4). The results showed that the lymphocytes secreted high amounts of IFN-γ in response to all the neoantigen peptides used, especially peptides 2, 4, and 6. We believe that cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognizing the neoantigen peptide may successfully provide surveillance against cancer recurrence, and that DC vaccination contributed to the prognosis of our patient, who is alive with no evidence of recurrence.

IFN-γ secretion in lymphocytes from PBMCs after the six course of neoantigen DC vaccination therapy was evaluated by ELIspot assay.

Since the primary objective of neoantigen DC vaccination is the induction of CD8 cancer-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes, this form of vaccination is mainly developed using class I peptides. CD4 helper T-cell activation using class II peptides and CD8 T cells have been recently shown to be important and highly effective in neoantigen DC vaccination [12]. Our procedure for DC administration involved ultrasound-guided intra-lymph node injection, as described previously [13]. The efficiency of DC migration to the lymph nodes with intra-lymph node injection is thought to be superior to that of subcutaneous injection, wherein only 1% of DCs reach the lymph nodes [14].

Neoantigen DC vaccination is a field with ongoing advancements. Although neoantigen vaccination is also gaining attention in Europe and the USA, studies in these regions are employing a form of mRNA vaccination instead of the cell therapy that we perform. While the safety of cell therapy with DCs has been established over the past 20 years, the long-term safety of mRNA vaccination has not yet been described.

Morisaki et al. showed that all seven patients with pancreatic cancer who underwent curative resection and received neoantigen DC vaccination survived with no evidence of recurrence for 2 years [15]. Another report showed that neoantigen DC vaccination monotherapy was effective in 15 of 17 chemotherapy-resistant patients, with 1 patient showing complete response; 2 showing partial response; and 11 showing stable disease [16].

With respect to the combination of neoantigen DC vaccination and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, neoantigen DC vaccination is theoretically expected to enhance the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors. In the Keynote-942 clinical trial, the group treated with pembrolizumab combined with neoantigen DC vaccination showed prolonged recurrence-free survival in comparison with the group treated with pembrolizumab alone [17]. Many clinical trials on the combination of neoantigen DC vaccination and immune checkpoint inhibitors are ongoing, and promising results are expected in the near future.

Neoantigen DC vaccination can be combined with conventional therapies, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, without restrictions and with few adverse effects. Neoantigen DC vaccination should be considered as an adjuvant therapy for several types of solid cancers and advanced cases with chemotherapy resistance.

Acknowledgement

This manuscript was edited by Editage Corp.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant numbers: JP22K08715, JP23K08073, and JP24K22147).

References

- cancer

- chemotherapy regimen

- colorectal cancer

- immunologic adjuvants

- pharmaceutical adjuvants

- dendritic cells

- genome

- immunologic surveillance

- peptides

- surgical procedures, operative

- t-lymphocytes, cytotoxic

- vaccination

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- neoplasms

- colon cancer

- i antigen

- dendritic cell vaccine

- transverse colon

- excision

- cancer immunotherapy