-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Asala Mohammad Awaysa, Bassam Adel Shawasha, Ro’a Rabah Samara, Nour Mufeed Amro, Sulaiman Naji Fares Fakhouri, Shadi Mohammad Saraheen, Unveiling the uncommon: a rare case of mesenteric cyst with unusual presentation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf758, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf758

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mesenteric cysts are rare and often enigmatic tumors that can arise from any part of the mesentery, spanning from the duodenum to the rectum. Due to their nonspecific symptoms, which can mimic a wide range of abdominal conditions, diagnosing these cysts can be particularly challenging. Here, we present the case of a 22-year-old female with no significant medical history, who underwent exploratory laparotomy for acute, generalized abdominal pain. During the procedure, she was diagnosed with a ruptured mesenteric cyst.

Introduction

Mesenteric cysts are uncommon, non-cancerous abdominal growths, with a 3% chance of developing into malignancy in reported instances. These cysts are often asymptomatic and can occur in any region of the abdomen. They are typically discovered either by chance or while addressing complications associated with them [1]. When they present with symptoms, mesenteric cysts typically lead to acute or recurring abdominal discomfort. They can also result in vague symptoms like loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, tiredness, and unintentional weight loss [2].

Typical sites of the mesenteric cysts include the mesentery of the small intestine (60%) or the colon (40%) and are classified into different types, including chylolymphatic, enterogenous, urogenital remnant (which are retroperitoneal but protrude into the peritoneum), and dermoid [3].

The exact cause of mesenteric cysts remains unknown, but potential contributing factors include a failure in the communication between lymph nodes and the lymphatic or venous systems, or obstruction of the lymphatic system due to previous pelvic surgery, trauma, pelvic inflammatory disease, infection, endometriosis, or tumors [4].

Diagnosis requires a combination of ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathological examination. Since mesenteric cysts can resemble various other types of cysts, early detection is crucial. Surgical excision of the cyst is the primary treatment, as it is key to preventing recurrence and the potential for malignant transformation [1].

Case presentation

A 22-year-old female patient, with free past medical and surgical history, who was referred to our hospital after having a computed tomography (CT) scan for her abdomen for her complaint of generalized abdominal pain for 3 days, that increased in severity and associated with episodes of vomiting and diarrhea; however, there were no history of fever, hematemesis, melena, or vaginal discharge. Additionally, there was no history of weight loss or recent abdominal trauma.

At the time of presentation, she was approximately at the end of her regular menstrual cycle.

There was no family history of a similar mesenteric disease, malignancy, or any congenital anomalies. Otherwise, she was fit and well with no previous medical history, with no previous surgeries or medication use.

On clinical examination, she was conscious, oriented, and afebrile. Her heart rate was 94 beats per minute, blood pressure 100 over 60, and temperature was 37.7. On abdominal examination, a mass was palpable in the right iliac fossa region with mild tenderness and distention without signs of peritonitis. There were no skin changes or dilated veins. On digital rectal examination, no external pathologies were found; no masses were palpable.

There were also no palpable lymph nodes. Her blood investigations revealed a raised white cell count of 10.8 × 109/l. Hemoglobin was 10.5 g/dl. Liver function tests showed alanine aminotransferase of 12 IU/l and aspartate aminotransferase of 27 IU/l. A C-reactive protein of 1.5 g/l.

An abdominal ultrasound showed right iliac fossa solid mass with anechoic center, measuring about 8.5 × 3.5 cm, both ovaries appear normal in size, shape, and echotexture with normal vascularity on Doppler study. No focal lesions were noted, few bilateral ovarian follicles measuring 3–5 cm with mild pelvic free fluids.

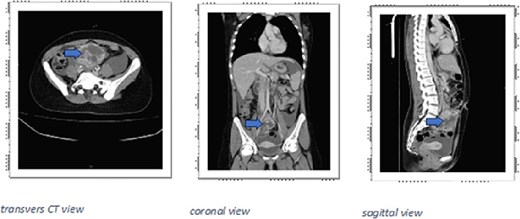

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large right pelvic ill-defined heterogeneously enhancing solid-cystic mass, with hyper density in non-contrast study, represents hemorrhage, measuring about 9 × 9 × 9.5 cm (AP × TS × CC diameter), the mass located below the aortic bifurcation and slightly compressing the right iliac vessels, associated with moderate ascites in the abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1).

CT scan large right pelvic ill-defined heterogeneously enhancing solid-cystic mass (arrows), with hyperdensity in non-contrast study, represents hemorrhage, measuring about 9 × 9 × 9.5 cm (AP × TS × CC diameter), the mass located below the aortic bifurcation and slightly compressing the right iliac vessels.

Accordingly, there was no need for urgent intervention, so the patient was admitted for observation.

At the next day, she was deteriorated, hemoglobin started to fall from 10.5 to 9.8 g/dl and then 8.1 g/dl. In addition, ultrasound showed severe free fluid with clots reaching Morrison’s pouch. So she was discussed with gynecology team and vascular surgery and their suspicions were rupture huge ovarian cyst versus rupture mesenteric cyst then the decision was going for an emergent exploratory laparotomy through a lower midline incision that revealed the following findings.

Intra-abdominal blood about 2000 cc, rupture cystic lesion about 10 × 10 cm suspected to originate from the mesentery and anterior wall of jejunum (about 15 cm from ligament of treitz). Cyst resection performed from its origin in the jejunal site and jejunal enterotomy done with primary repair for jejunal wall with a cautious dissection of the adhesions of the sigmoid wall and posterior abdominal wall. Intraoperatively, right rectal drain applies in the pelvis, left rectal drain applies in site of jejunal repair, and nasogastric tube applied.

Biopsy sent for histopathological evaluation, which identified a benign mesenteric cyst with hemorrhage, fibrosis, and fibroblastic proliferation, negative for malignancy.

In the postoperative course, she was received two units of blood and she was fine throughout her hospital stay, which lasted 6 days after surgery, then she was discharged home in a good medical condition.

Discussion

Mesenteric cysts are uncommon, non-cancerous growths that can either be asymptomatic or present with symptoms resembling those of a mass lesion [1]. The exact origin of mesenteric cysts is unclear, though several theories have been proposed. These include the continued growth of congenitally abnormal or misplaced lymphatic tissue, trauma, degenerating lymph nodes, or improper fusion of the mesenteric leaves. The variety of these theories suggests that multiple etiological factors may contribute to the development of mesenteric cysts [5].

Assessing patients with mesenteric cysts is by abdominal CT, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging all are useful for assessment. When possible, straightforward mesenteric cysts should be surgically removed [1].

Conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis include hydatid cysts, lymphangiomas, ovarian cysts, peritoneal cysts, and cystic teratomas [6]. A mesenteric cyst can present a diagnostic challenge; however, it can be distinguished through a thorough history, physical examination, and radiological imaging [7].

Unroofing or marsupialization of the cyst is generally discouraged, as drainage alone has a high likelihood of recurrence. In rare instances, when the mesentery is adhered, it may need to be excised to achieve complete removal, which may require performing a segmental bowel resection [1].

Mesenteric cysts can occur in patients of all ages, with approximately one-third of cases found in children under 15. These cysts may present as acute abdominal pain, be found incidentally, or manifest with nonspecific abdominal symptoms. Often asymptomatic, they are typically discovered incidentally during the evaluation or treatment of other conditions, such as appendicitis, small-bowel obstruction, or diverticulitis [6]. However, patients can present with lower abdominal pain.

Ultrasonography is commonly used in women with acute lower abdominal pain to diagnose ovarian cysts, but in rare cases like this, it can result in a misdiagnosis. It has been proposed that CT and MRI are more effective imaging techniques for assessing the location and characteristics of a suspected mesenteric cyst before surgery [8].

When female patients present to the emergency department with lower abdominal pain and a negative pregnancy test, surgeons should consider ruptured or infected mesenteric cysts as part of the differential diagnosis. Literature cases have reported instances where such conditions were initially misdiagnosed as appendicitis or ovarian cysts [8].

In this case, the patient’s unspecific abdominal pain without any characteristic signs on examination making the diagnosis challenging. Beyond clinical manifestations, the patient needs to undergo a complete assessment through radiological findings using abdominal ultrasound, CT scan.

The preferred treatment to prevent recurrence and reduce the risk of malignant transformation is complete surgical excision, which may involve removing part of the mesentery along with the mass. Cyst removal can be performed through either laparotomy or laparoscopy [4].

After complete excision, the recurrence rate is typically low, but follow-up is recommended to detect any potential recurrence early. Overall, the prognosis for mesenteric cysts is favorable, as most are benign [9].

Conclusions

Mesenteric cysts are rare tumors that can develop anywhere along the mesentery of the bowel, from the duodenum to the rectum. In this case, the patient’s preoperative diagnostic imaging strongly indicated the presence of a mesenteric cyst, and intraoperative findings confirmed the cyst’s location and size as consistent with the radiographic results. In conclusion, mesenteric cysts are unique clinical entities that necessitate a multidisciplinary approach, involving collaboration between radiology, surgery, and pathology, to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.