-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Toshimitsu Irei, Tetsuji Harada, Naotsugu Yamashiro, Haruka Motonari, Yoshiki Hori, Nao Kinjo, Junya Arakaki, Hironori Samura, Fumiko Kohakura, Yoshitetsu Nagamine, Shinichiro Kameyama, Tomonari Ishimine, Perioperative and long-term outcomes of pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a case series of eight patients, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 12, December 2025, rjaf911, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf911

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This report retrospectively evaluated the perioperative and long-term outcomes of eight cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) in patients undergoing hemodialysis. The median age and duration of hemodialysis of the patients were 68 and 6 years, respectively. The Preoperative Charlson Comorbidity Index and abdominal aortic calcification scores were generally high. The median operative time and blood loss volume were 454 min and 673 ml, respectively. The 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0%; however, Clavien–Dindo grade ≥IIIa postoperative complications occurred in four cases, with one in-hospital death due to superior mesenteric artery thrombosis 6 months postoperatively. Six of the eight patients died within 8 years due to causes other than cancer recurrence. Although PD is technically feasible for patients undergoing hemodialysis, it is associated with significant perioperative and long-term risks. Therefore, careful patient selection through preoperative counseling and multidisciplinary management is essential to achieve the best possible outcomes.

Introduction

The number of patients on hemodialysis for end-stage renal failure and undergoing surgical procedures, including abdominal surgery, has been increasing steadily, reflecting advancements in medical care and improved life expectancy [1]. However, these patients present unique challenges during surgery due to their altered physiological status, including compromised cardiovascular function, vascular calcification, and heightened susceptibility to infection [2, 3]. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex surgical procedure often performed for malignant or premalignant diseases of the pancreas and periampullary region and poses significant risks, even in the general population; however, the feasibility of PD in patients undergoing hemodialysis remains unclear. In particular, there have been few reports on the long-term outcomes of PD in patients undergoing hemodialysis. This case series aimed to report and evaluate the perioperative and long-term outcomes of PD in patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Case series

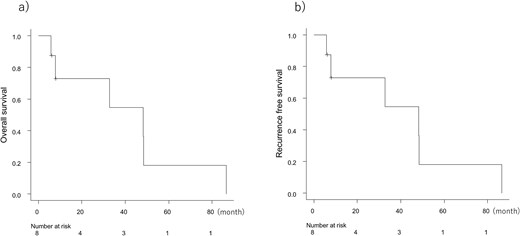

This retrospective case series included all patients on hemodialysis who underwent PD at our institution between January 2012 and June 2023. Preoperative clinical variables, including comorbidities and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [4], perioperative clinicopathological variables, and long-term survival data were extracted from electronic medical records. To evaluate the calcification of blood vessels, the abdominal aortic calcification (AAC) score was quantified using the Agatston method [5] from 30 contiguous sections (3 mm thickness) starting from the origin of the celiac artery using the automatic program of the ZIOSTATION REVORAS software (Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan) based on a non-contrast abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan during the 3-month perioperative period. Postoperative complications were classified using the Clavien–Dindo grading system. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method in EZR software.

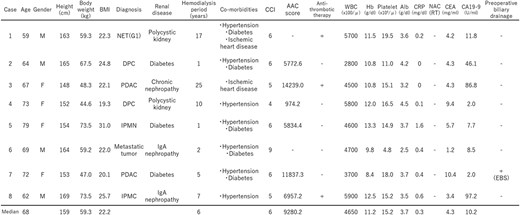

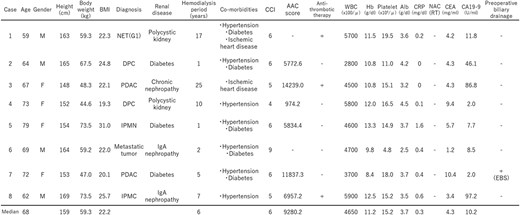

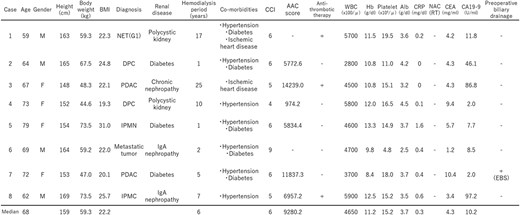

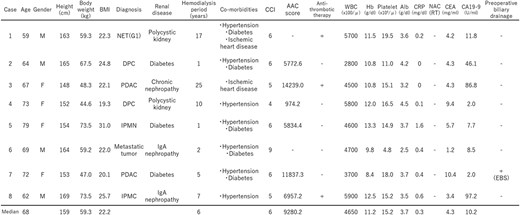

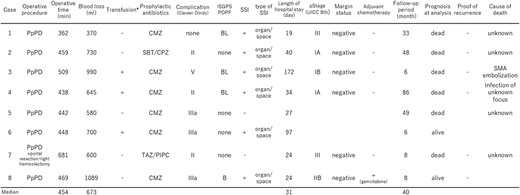

The study cohort comprised eight patients (four men and four women) with a median age of 68 years (range, 59–79 years), and 4.0% of the 198 patients underwent PD during the study period. The pathogenesis of kidney disease included diabetes (in three cases), immunoglobulin A nephropathy (in two cases), polycystic kidney disease (in two cases), and other causes (in one case). The median duration of hemodialysis was 6 years (range, 1–25 years). All eight patients had comorbidities, including hypertension (seven cases), ischemic heart disease (two cases), and diabetes (five cases). The preoperative CCI of the patients was generally high, with a median of 6 and a range of 4–9. For all patients, there was clear evidence of AAC on CT scans, with the AAC scores of the six patients for whom a score could be determined being extremely high, with a median value of 9280.2 and a range of 974.2–14329.0. The indications for surgery included pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (two cases), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with or without carcinoma (two cases), duodenal papillary cancer (two cases), neuroendocrine tumor (one case), and metastatic disease (one case). Six of the eight patients had primary malignant diseases of the peripancreatic head (Table 1). All patients underwent pylorus-preserving PD. One patient required additional portal vein resection and right hemicolectomy because of tumor invasion. The median operative time was 454 min (range, 362–681 min), and the median blood loss was 673 ml (range, 370–1089 ml). All patients underwent hemodialysis a day before surgery and resumed hemodialysis on postoperative day 1 under the supervision of a nephrologist, along with the management of fluid volume. We stringently managed blood sugar during the perioperative period of PD under the supervision of diabetes specialists. One patient was taking aspirin and clopidogrel sulfate after coronary artery bypass grafting, preoperatively and after a heparin switch for one week before and after surgery, heparin and antiplatelet agents were discontinued under the supervision of a cardiologist. Postoperative complications were graded as Clavien–Dindo 0–I in one case, grade II in three cases, and grade ≥ IIIa (major complication) in four cases, which comprised 50% of the cohort. Major complications included blood access site reconstruction, continuous drainage for pancreatic fistulas or abdominal infections, and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) thrombosis. Six patients had surgical site infection (SSI), and all patients had organ/space SSI. The 30- and 90-day mortality rates were 0%; however, one patient died during hospitalization due to SMA thrombosis 6 months after surgery. The median hospital stay was 31 days (range, 19–172 days). The median follow-up period was 40 months, and two patients were alive at the time of analysis. The median survival time for the cohort was 48 months (range, 6–86 months), and the 5-year OS and RFS rates were 18.2% (Fig. 1). In particular, the causes of death included SMA thrombosis (one case) 6 months postoperatively and non-cancer causes (five cases) within 8 years postoperatively in other cases (Table 2).

Preoperative clinical variables of eight cases on hemodialysis who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy

|

|

BMI, body mass index; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; DPC, duodenal papillary cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; IPMC, intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma, CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index, AAC, abdominal aortic calcification, NAC(RT), neoadjuvant chemotherapy (radiation therapy), EBS, endoscopic biliary stenting.

Preoperative clinical variables of eight cases on hemodialysis who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy

|

|

BMI, body mass index; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; DPC, duodenal papillary cancer; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; IPMC, intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma, CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index, AAC, abdominal aortic calcification, NAC(RT), neoadjuvant chemotherapy (radiation therapy), EBS, endoscopic biliary stenting.

(a) Overall survival and (b) recurrence free survival of eight cases on hemodialysis who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy.

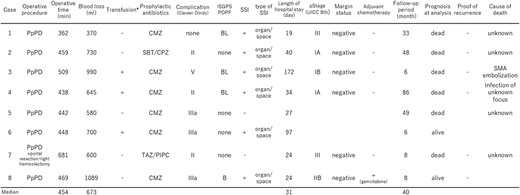

Perioperative clinicopathological variables and long-term outcomes of eight cases on hemodialysis who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy

|

|

PpPD, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy; CMZ, cefmetazole; SBT/CPZ, sulbactam/cefoperazone; TAZ/PIPC, tazobactam/piperacillin; ISGPS, international study group on pancreatic surgery; POPF, post operative pancreatic fistula; SSI, surgical site infection; SMA, superior mesenteric artery. *During surgery and during the 72-h post operative period.

Perioperative clinicopathological variables and long-term outcomes of eight cases on hemodialysis who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy

|

|

PpPD, pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy; CMZ, cefmetazole; SBT/CPZ, sulbactam/cefoperazone; TAZ/PIPC, tazobactam/piperacillin; ISGPS, international study group on pancreatic surgery; POPF, post operative pancreatic fistula; SSI, surgical site infection; SMA, superior mesenteric artery. *During surgery and during the 72-h post operative period.

Discussion

The present study highlights that PD is technically feasible for patients undergoing dialysis, considering the intraoperative amount of bleeding and operation time, but involves considerable perioperative and long-term risks.

In terms of short-term outcomes, the 30- and 90-day mortality rates were both 0% in our study, despite the generally high preoperative CCI values of the patients. However, the rate of major complications was high (50% patients with Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ IIIa), which underscores the challenges of managing this high-risk group. Shinkawa et al. examined the short-term outcomes of pancreatic resection in patients undergoing dialysis. In their cohort, 307 (1.0%) of 30 495 patients undergoing PD were on dialysis. Their data showed that the postoperative complication rate of PD in patients undergoing dialysis was significantly higher for peritonitis, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), intra-abdominal bleeding, acute coronary events. Moreover, the 30-day (5.2%) and 90-day (17.3%) mortality after PD for patients on dialysis was significantly higher than that for patients not on dialysis, with 30- and 90-day mortalities of 0.7% and 1.9%, respectively; however, the cause of death has not been reported. They emphasized that PD in patients on dialysis should be carefully monitored, considering the development of postoperative intra-abdominal bleeding, peritonitis, sepsis, DIC, and acute coronary events [6]. The four cases with major complications in the present study included continuous abdominal drainage for infection in two cases and thromboembolic complications in two cases (reconstruction for blood access and SMA embolization).

Regarding the prevention of infection during the perioperative period, based on previously reported findings [7] and data on bile cultures obtained before PD at our hospital, perioperative prophylactic antibiotics for PD surgery, including for patients undergoing hemodialysis, were selected according to the following principles. In cases without preoperative biliary drainage, cefmetazole, which is effective against gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes, and tazobactam/piperacillin, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent with efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, were used in cases in which endoscopic biliary tube stents were placed. In cases of endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, antibiotics based on the latest surveillance culture of bile juice were administered for 3 days, including on the day of surgery. The perioperative infections in a number of the cases reported herein were organ/space SSI associated with postoperative pancreatic fistulas. Given careful drain management and selection of appropriate antibiotics on a case-by-case basis, the infection did not directly lead to mortality. However, cases in which bacteria not targeted by prophylactic antibiotics were detected immediately after surgery, and the selection of broad-spectrum antibiotics for immunovulnerable patients undergoing hemodialysis and PD should be reconsidered.

Another postoperative concern in patients undergoing hemodialysis and PD is thrombotic complications. The prevalence of both atherosclerosis and cardiovascular complications is known to be high in dialysis patients. In recent years, AAC has been reported to be an important predictor of cardiovascular complications, including coronary heart disease [8]. A positive correlation exists between dialysis history and AAC score [9]. In terms of the association between AAC scores and postoperative complications, kidney and pancreas-kidney transplant recipients with high AAC scores, in which all patients have renal insufficiency, have been reported to have 3-fold higher postoperative cardiovascular and mortality risk than those without AAC [10]. In the present study, CT imaging revealed clear AAC with extremely high scores in all patients for whom the AAC score could be determined, indicating a particularly high risk of postoperative cardiovascular complications. Moreover, patients with postoperative SMA thrombosis have the highest AAC scores. Although no definite prophylaxis has been reported to date, appropriate fluid management and monitoring of thrombus formation will continue to be important for preventing thrombotic complications and failure to rescue patients with high AAC levels during the perioperative period of PD surgery. Prevention of vascular calcification includes phosphate control with non-calcium-based binders; restriction of calcium and vitamin D use; vitamin K supplementation; and management of secondary hyperparathyroidism, inflammation, and acid–base balance [11]. Implementing these strategies will contribute to the reduction of preoperative vascular calcification and cardiovascular complications following PD surgery in patients undergoing dialysis.

In terms of long-term outcomes and prognostic implications, the 5-year OS rate of 18.2% in our study reflects the dual burden of malignancy and comorbidities in this population. Teraoku et al. have reported long-term outcomes in four patients who underwent pancreatectomy, including two cases of PD in patients on dialysis. Their data showed that three of the four patients who underwent pancreatectomies for dialysis died within 6 months postoperatively, and both patients who underwent PD for pancreatic cancer died within 6 months of causes unrelated to cancer [12]. PD surgery for high-risk patients on dialysis is likely to be performed in a very limited manner, and to our knowledge, our data of eight cases are the largest number of reports on long-term outcomes after PD for patients undergoing hemodialysis. Understanding the cause of death after PD surgery in patients undergoing hemodialysis is important. Most of the deaths in our study were unrelated to cancer recurrence. In our study, one case was due to complications 6 months postoperatively, and the other five cases were caused by unproven cancer recurrence, including unexplained sudden death. These results highlight the importance of addressing noncancerous comorbidities after PD surgery in patients undergoing hemodialysis to obtain better outcomes.

This study was limited by its retrospective design and small sample size from a single institution. Additionally, future studies should incorporate quality-of-life assessments, which our study did not validate, to better understand the broader impact of PD in this population.

Although PD is technically feasible in patients with pancreatic disease who are undergoing hemodialysis, it is associated with significant perioperative and long-term risks. Therefore, careful patient selection through preoperative counseling and multidisciplinary management is essential to achieve the best possible outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing and Mr. Kazuhide Miyazato, a radiological technologist, for his assistance in determining the AAC scores.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval and/or institutional review board approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Urasoe General Hospital (Approval Number 2025-001).