-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mahmoud K Abd-El-Hafez, Todd D Beyer, Megan K Applewhite, Retrograde intussusception in pregnancy following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf637, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf637

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Intussusception is the invagination of the bowel onto itself. Because of the unary nature of peristalsis, most cases of intussusception are anterograde, making retrograde intussusception exceedingly rare. We herein present a 23-year-old female in her 36th week gestation with a 24-hour history of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and hematemesis, 3 years following a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Abdominal computed tomography with subsequent exploratory laparotomy confirmed the diagnosis of retrograde intussusception at the jejunojejunostomy anastomosis. The jejunojejunostomy along with the proximal jejunal common channel was resected, and a new jejunojejunostomy anastomosis was reconstructed. Patient was discharged on postoperative day (POD) 9 with systemic anticoagulation for superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. There are very few documented cases in the literature of retrograde intussusception following gastric bypass procedures in pregnant women.

Introduction

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the second most common bariatric surgery, accounting for >41 000 cases in the United States in 2017 [1]. Retrograde intussusception is a rare complication of Roux-en-Y procedures that represent as little as 2.7% of post-operative intussusception according to one institutional review [2]. Intussuception is a medical emergency that occurs when peristaltic waves dislodge the proximal bowel (intussusceptum) onto itself (intussuscepien) distally. The unary nature of peristalsis makes retrograde intussusception exceedingly rare.

Intussusception results in luminal obstruction, which presents clinically as the characteristic blood/currant jelly stool from intestinal epithelial necrosis. Most cases occur in children, while only 5% of all intussusception cases occur in adults [3]. Most cases of documented retrograde intussusception in adults has been seen following RYGB and other gastroenterostomy procedures [4]. There is evidence to believe that a large number of post-operative intussusception cases go on undiagnosed since only 46% of cases present with at least three of the four ‘classic features’ of vomiting, abdominal pain, blood/currant jelly stool, and abdominal mass [5]. The number of RYGB procedures continue to rise every year and women represent the majority (70%) [6]. As many of these women are of reproductive age, the likelihood of encountering surgery-related small bowel obstruction, such as internal hernias, intussusception, or volvulus following RYGB is between 1.5% and 3.5% [6]. As a result, it is critical for surgeons to consider retrograde intussusception whenever a patient with a history of RYGB present with abdominal pain and vomiting [2]. We here present a case of retrograde intussusception in a 23-year-old, 36-week pregnant female 3 years following RYGB.

Case report

A 23-year-old female presents in her 36th week gestation of an uncomplicated pregnancy with a 24-hour history of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and hematemesis. Her last bowel movement was 16 hours prior. Her past medical history was notable for morbid obesity, treated surgically with RYGB. Her gastric bypass surgery was complicated by an internal hernia and a perforated marginal ulcer, both requiring surgical interventions. Other surgical history includes cholecystectomy, appendectomy, and cesarean section.

On physical exam patient was afebrile and hemodynamically normal. Her obstetric exam was unremarkable and fetal biometric markers were as expected. Her abdomen was soft, gravid, and nonperitonitic, but focally tender in the left upper quadrant (LUQ). Her laboratory studies were remarkable for a mild anemia with a hemoglobin of 9.7, white count of 9.4, and a normal lactic acid of 1.35.

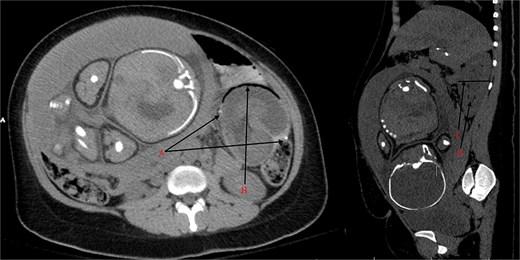

Transvaginal ultrasound showed no evidence of placental abruption and a viable fetus. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen/pelvis was concerning for intussusception in the LUQ at the jejunojejunostomy anastomosis, causing a small bowel obstruction and radiographic evidence of ischemia (Fig. 1). Patient was taken for an exploratory laparotomy and a concomitant cesarean section. Following an uneventful cesarean section, the LUQ was explored. A 20-cm dusky segment of the proximal common channel had telescoped retrogradely into the jejunojejunostomy anastomosis, causing a complete small bowel obstruction. The afferent and Roux limbs were dilated but viable. Following unsuccessful attempts at reducing the intussusception, the entire jejunojejunostomy anastomosis was resected and reconstructed.

(A) Staple line of the jejunojejunostomy anastomosis. (B) Pneumatosis intestinalis from the ischemic intussusceptum. (C) Cross-section of the intussuscipiens measuring up to 6.3 cm (n ≈ 3 cm). (D) Mesenteric vessels in the lumen on the intussucipiens.

Pathology demonstrated small intestine with focal ischemic necrosis and adventitial adhesions. Her postoperative course was unremarkable, except for an acute thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein detected on CT scan on POD 5 for recurrent abdominal pain. The patient was discharged by POD 9 with systemic anticoagulation.

Discussion

Intussusception is a rare, yet life-threatening emergency that accounts for 1%–3% of all causes of bowel obstruction [7]. Patients who undergo bariatric surgeries, like RYGB, carry a higher risk of developing intussusception compared to the general population. There is an estimated 0.07%–0.6% lifetime risk of developing intussusception following bariatric surgery [8]. The reason for this increased prevalence is unclear and likely multifactorial. One possible explanation is that the junctions between the free and fixed segments of small bowel following bariatric surgery can act as lead points and are particularly prone for intussusception. Second, extensive weight loss creates a thin and floppy mesentery, and thus leads to hypermobility of the small bowel during peristalsis. This hypermobility is thought to be associated with intussusception, particularly through stable lines [9]. Lastly, peristaltic activity through the Roux limb following gastric bypass surgery is thought to be inappropriate and predisposes the limb for intussusception and internal hernia, as discussed in one documented case [10].

This case was particularly novel because of the antiperistaltic nature of the intussusception. Less than 3% of post-surgical intussusceptions are retrograde and there are only a few other documented cases of pregnant patients presenting with retrograde intussusception following bariatric surgery. Diagnosis is often difficult to make because of the lack of clinical signs. The nonspecific symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting can have various etiologies. In one reported case, elevated pancreatic enzymes in conjunction with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting was misdiagnosed for acute pancreatitis and was later discovered to be a closed loop, retrograde jejunojejunal intussusception [11]. Additionally, the classic triad of pain, bloody stools and palpable mass is rarely seen with retrograde intussusception, compared to the more common anterograde form [12].

Imaging modalities can be used to supplement clinical suspicion when making a definitive diagnosis. Currently, CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosing intussusception in the nonpregnant adult population. It has a reported sensitivity between 66% and 78% [13]. Its high radiation burden makes it an unrealistic choice for pregnant patients in their first trimester. Instead, an ultrasound or MRI should be used. A CT scan can still be a viable imaging modality for pregnant patients in their second and third trimester [14]. The potential radiation harm to the fetus is offset by the potential for a rapid diagnosis, especially in a hemodynamically unstable patient. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be considered. Ultimately, definitive diagnosis is made when exploratory laparotomy is performed.

Acknowledgements

There are no personal financial disclosures, non-financial support, or conflict of interest to be acknowledged during the making of this case report. This research was supported (in whole or in part) by Albany Medical College, Albany Med Health System, and/or Albany Med affiliated entities. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of Albany Med Health System or any of its affiliated entities. No external funding was obtained for the completion of this case report.

Conflict of interest statement

No other financial disclosures or conflict of interest.

Funding

None declared.