-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mohamed Amine Selmene, Malek Bachar, Mondher Mbarek, Mourad Zaraa, Customized 3D-printed drill guide for surgical resection of osteoid osteoma in the ischiopubic ramus, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf627, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf627

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Osteoid osteoma is a common benign tumour. It mainly affects the long bones and spine. The pelvic ring is a rare localization for it. We report the case of a 24-year-old woman who complained of buttock pain, mainly nocturnal and resistant to the usual medical analgesic treatment and radiating to the lateral region of the left hip. Pelvis X-rays and computed tomography scan showed an osteoid osteoma located in the left ischiopubic ramus. We performed a minimally invasive resection of this tumour using a custom-made 3D-printed drill guide. We noted no operative incidents, and the patient no longer complained of tumour-related pain in the immediate postoperative period. At 24-month follow-up, the patient was pain-free and we did not note recurrence of the tumour. The 3D printing of a customized guide for surgical drilling of an osteoid osteoma with a rare and deep-seated location such as the pelvis is an interesting alternative in its nonconservative treatment.

Introduction

Osteoid osteoma is one of the most common benign bone tumours after enchondromas and nonossifying fibromas [1]. It mainly affects the long bones and spine. The pelvic ring is a rare site for this tumour [2]. Surgical treatment options range from radiofrequency ablation to computed tomography (CT)-guided drilling, as well as percutaneous or open surgical resection.

We report the case of an osteoid osteoma of the ischiopubic ramus resected minimally invasively using a custom-made 3D-printed drill guide.

Case report

We report the case of a 24-year-old woman with no particular pathological history who complained of buttock pain radiating to the lateral region of the hip and which had been present for 8 months. Most of the pain was nocturnal, resistant to the usual medical analgesic treatment. No spinal or knee symptoms were reported. Clinical examination revealed a well-localized tenderness over the left buttock, corresponding to the ischial region. Mobilization of the hip and knee was painless. Pelvis X-rays showed a millimetric radiolucent area surrounded by an osteosclerosis at the ichiopubic ramus of the left obturator frame (Fig. 1A). The appearance was in favour of an osteoid osteoma. Computed tomography supported the diagnosis (Fig. 1B).

(A) Osteoid osteoma of the left ischiopubic ramus on the anteroposterior view of a pelvic X-ray. (B) Osteoid osteoma of the left ischiopubic ramus on an axial section of the CT scan of the pelvis.

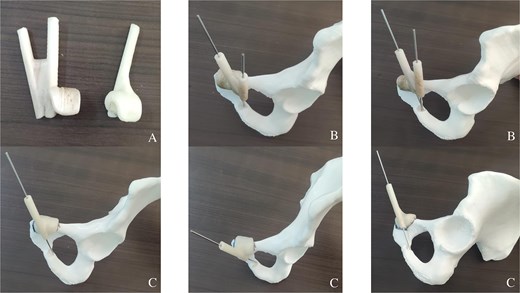

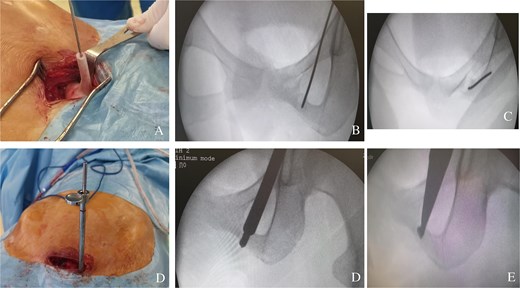

The patient received acetylsalicylic acid, with partial clinical improvement. The decision was made to perform a surgical drilling and curettage of the tumour with the help of a customized 3D-printed guide (Fig. 2A–C). The patient underwent surgery on a standard table, in supine position, under general anaesthesia. A mini-Pfannenstiel approach (on the pubic symphysis) was performed to expose the proximal and medial border of the left iliopubic ramus, which served as a fixed landmark for positioning the guide (Fig. 3A). Once the guide had been pinned in place, a K-wire was inserted in the direction of the tumour. A fluoroscopic check verified the K-wire positioning (Fig. 3B). A soft tissue protection instrument was used to guide the cannulated drill bit towards the tumour (Fig. 3C). Drilling and curettage of the lesion was performed under fluoroscopic control with anteroposterior, inlet, and outlet views of the pelvis (Fig. 3D and E). The anatomopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma, which was completely resected. Pain disappeared in the immediate postoperative period. At 24-month follow-up, we did not note recurrence of the tumour (Fig. 4A and B). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

(A) Two customized 3D-printed drill guides for more precision. (B) A customized 3D-printed drill guide with two K-wires positioned in the direction of the tumour. (C) A customized 3D-printed drill guide with one K-wire positioned in the direction of the tumour.

(A) Positioning the guide on the iliopubic ramus via a mini-Pfennestiel approach. (B) Anteroposterior fluoroscopic control of the correct position of the K-wire in the tumour. (C) Fluoroscopic inlet view showing the correct position of the K-wire in the tumour. (D) A soft tissue protection instrument as a guide for the cannulated drill. (E) Curettage of the tumour.

(A) Immediate anteroposterior pelvis X-ray showing the tumour resection. (B) Last follow-up anteroposterior pelvis X-ray showing the absence of tumour recurrence.

Discussion

Osteoid osteoma is the most common benign osteoblastic bone tumour [2]. It most frequently affects young males, with a predilection for the 10–30 age group [1, 2]. Clinically, this tumour manifests as a painful symptomatology with nocturnal recrudescence, which can be partially or totally relieved by salicylic acid [1, 2].

Diagnosis is often difficult because of the variability of the tumour in terms of localization and thus clinical expression, especially in deep-seated sites [2]. In two-thirds to three-quarters of cases, osteoid osteomas are located in the long bones (femur, tibia, etc.) and in the spinal column [1, 2]. Secondarily, the bones of the foot and hand are affected by this tumour [1]. In the pelvic girdle, osteoid osteoma is located either in the proximal part of the femur or in the acetabulum, which remains a rare localization described in a few case reports in the literature [3, 4]. Less frequently, the pelvic ring can be affected in 1%–3% of cases [2]. According to the literature, an osteoid osteoma may have mainly either a sacral or an iliac wing location [2, 5, 6]. A location in the obturator ring, and especially in the ischiopubic ramus as in our patient, has not been reported in the literature to our knowledge.

Diagnosis of an osteoid osteoma may be delayed due to confusing symptomatology, particularly in deep localizations such as the pelvic ring [2]. Standard radiography may be inconclusive in certain situations, and CT scan allows visualization of the typical lesion of this tumour consisting of a round radiolucent area surrounded by a border of osteosclerosis [7].

Treatment of osteoid osteomas should initially be conservative, with salicylates and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Response to this treatment is variable, with success ranging from 30% to 70% in the literature [8]. Failure of this kind of treatment, intolerance to prolonged use of the drugs used, or significant limitation of daily activities leads to a nonconservative treatment [1].

Surgery to remove osteoid osteomas can be performed openly, with en bloc resection or curettage of the lesion, with a very high success rate at the expense of the morbidity of the surgical procedure [1]. It can also be performed arthroscopically, particularly in the case of articular localization [9]. CT-guided drilling joins these minimally invasive techniques and is currently one of the most widely practised techniques for treating this tumour. Its results are comparable to open surgery with a better aesthetic appearance and it is more cost-effective [10, 11]. For tumours > 1 cm in size and far from neurovascular structures [2], radiofrequency ablation or cryoablation can be performed with 3D guidance. They have a high success rate of ~98% and can be performed outside the operating room [12, 13]. These minimally invasive techniques have been described as safe and cost-effective, but in some situations were associated with a higher rate of recurrence than surgical resection [14].

Our technique combines a customized 3D-printed guide and drilling–curettage of the lesion by minimally invasive surgery, to ensure the best possible success rate. To our knowledge, this technique has not been described in the literature for the treatment of osteoid osteoma. It is innovative, safe, and does not cost more than other therapeutic alternatives. It combines the advantages of minimally invasive surgery with the precision of CT guidance. For new technologies by now, navigation coupled with 3D imaging is gaining ground in orthopaedic surgery, and its indication could be extended to the treatment of osteoid osteomas [15].

Conclusion

The 3D printing from CT imaging of a customized guide for surgical resection or drilling of a bone tumour should be considered in the nonconservative therapeutic arsenal for osteoid osteomas, particularly those of deep pelvic or spinal location. This technique requires careful preoperative planning to ensure that the wires are positioned correctly in the direction of the tumour and to prepare the bony landmark on which the guide will be positioned.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

We declare that we have not received any funding for the completion of this work.