-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Luis F Llerena Freire, Giannella I Llerena Freire, Chylous ascites as a postoperative complication of a robot-assisted D3 extended right hemicolectomy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf622, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf622

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chylous ascites is the accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the peritoneal cavity due to disruption or obstruction of abdominal lymphatic vessels. It typically presents as painless abdominal distention and is diagnosed by the presence of elevated triglycerides in the ascitic fluid. Although malignancy is the most common cause, abdominal surgery should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Treatment is primarily conservative and includes a high-protein, low-fat diet with medium-chain triglyceride supplementation. In cases with poor response or contraindications to enteral nutrition, total parenteral nutrition is indicated, reserving surgical intervention for refractory cases. We report a rare case of chylous ascites following a robot-assisted D3 extended right hemicolectomy, successfully managed with conservative therapy.

Introduction

The lymphatic system is a complex network of capillaries and vessels that converge at the thoracic duct, which drains its contents into the venous circulation. Lymph is a fluid composed of interstitial fluid, proteins from peripheral tissues, non-soluble fats absorbed in the intestine, and lymphocytes originating from lymph nodes and organs. Normal lymphatic flow ranges from 2 L to 4 L per day [1, 2].

Chylous ascites is defined as the accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the peritoneal cavity due to rupture or obstruction of abdominal lymphatic vessels [3]. The condition is most commonly associated with malignancies, liver cirrhosis, and abdominal surgeries. While its incidence in the latter can reach up to 11%, it remains rare following colorectal surgery, which may delay diagnosis and treatment [4].

In this report, we describe a case of chylous ascites following a D3 extended right hemicolectomy for ascending colon cancer. The clinical relevance of this case lies in the potential for both local (mechanical) and systemic (nutritional and immunological) complications, which may lead to high morbidity or mortality if not promptly managed. The patient was successfully treated with conservative measures, including a high-protein, low-fat diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient, and all identifying data have been removed. This case report was prepared in accordance with the CARE guidelines [5].

Case presentation

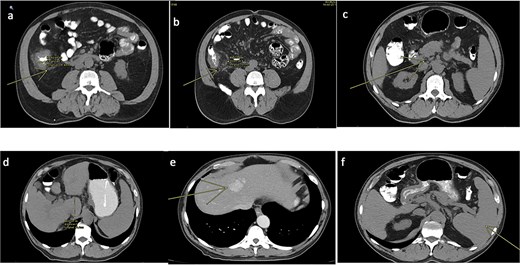

A 77-year-old male with a medical history of right-sided colon cancer was diagnosed by colonoscopy, which revealed an obstructive tumor at the level of the cecum. An abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a circumferential and irregular thickening consistent with a tumor in the cecum, associated with pericolic fat stranding, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, altered mesenteric fat, signs of chronic liver disease, a hepatic hemangioma, splenomegaly, and features of portal hypertension (Fig. 1).

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (non-contrast). (a) Tumoral concentric thickening of the cecum with pericolic and mesenteric fat stranding. (b) Infiltrative-appearing lymphadenopathy adjacent to the tumor. (c) Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. (d) Signs of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension. (e) Hepatic hemangioma. (f) Splenomegaly.

The colonoscopic biopsy confirmed a moderately differentiated infiltrating adenocarcinoma. Given the tumor burden and the risk of intestinal obstruction, the patient underwent a robot-assisted D3 extended right hemicolectomy with ileotransverse anastomosis. The immediate postoperative course was uneventful.

Approximately one month later, the patient presented to the emergency department with generalized abdominal pain and distension of 24 h duration. Physical examination revealed a distended, diffusely tender abdomen with signs of ascites. The patient had an abdominal drain in place, which showed milky fluid output.

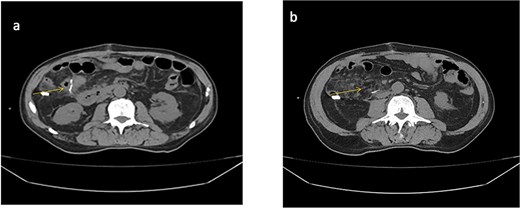

A follow-up abdominal CT scan revealed post-surgical changes consistent with a right hemicolectomy and ileotransverse anastomosis, along with a moderate amount of free intraperitoneal fluid (Fig. 2).

Abdominal CT scan (non-contrast). (a) Anastomotic staples and drain trajectory. (b) Presence of free intraperitoneal fluid.

Given the appearance of the ascitic fluid (Fig. 3), a diagnostic paracentesis was performed. The fluid analysis showed leukocyte count of 12 362/μL (81.7% polymorphonuclear cells), and triglyceride level of 981 mg/dL, consistent with chylous ascites.

Image of chylous ascitic fluid collected through the abdominal drain, showing its characteristic milky appearance.

With a diagnosis of moderate protein-calorie malnutrition and chylous ascites, the patient was admitted for conservative management, including total parenteral nutrition (soybean oil, medium-chain triglycerides, olive oil, fish oil, and amino acids), oral diet restriction, intravenous hydration with 0.9% saline, and empirical antibiotic therapy. The patient remained hemodynamically stable and showed clinical improvement.

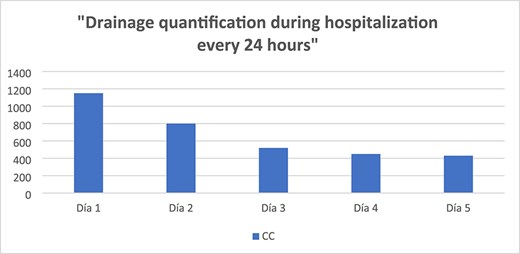

The drain output was monitored daily (Fig. 4). By hospital day 5, the output had decreased to 430 cc/day, and the fluid had become clear (Fig. 5). A soft diet was reintroduced. On day 6, repeat fluid analysis revealed a triglyceride level of 123 mg/dL, indicating resolution of the chylous leak. The patient was discharged on day 7 with outpatient follow-up.

Image of ascitic fluid on day 5 of hospitalization, showing clearer appearance indicating reduced chyle content.

Postoperative follow-up

At the day 13 follow-up, a minimal amount of ascitic fluid was still draining, prompting drain removal. The patient was instructed to undergo paracentesis if significant abdominal distension recurred. He is scheduled to receive adjuvant therapy based on the final pathology report showing well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (G1), tumor stage pT3-pN0, and positive cytology in the ascitic fluid consistent with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Discussion

Chylous ascites is characterized by the milky, odorless, and sterile appearance of the ascitic fluid. It is an infrequent condition described in the literature, with few surgeons having encountered it, which complicates its diagnosis and management. The global incidence is ⁓1 in 187 000 cases, increasing due to the growing number of complex and advanced oncologic abdominal surgeries. Mortality rates are relatively low, ranging from 7.7% to 11% [6].

Physical examination is essential and should be considered alongside surgical history, trauma, and hepatorenal diseases. The most common clinical presentation is painless abdominal distension, although it can less frequently present as an acute abdomen [7]. Additional symptoms include diarrhea, malnutrition, early satiety, dyspnea, lower limb edema, nausea, lymphadenopathy, and weight fluctuations [8].

Physical findings may reveal a positive fluid wave, signs of cirrhosis, palpable abdominal or cervical masses suggestive of malignancy, and auscultatory changes indicating pleural effusion.

Etiologically, chylous ascites is classified as traumatic or atraumatic. Our patient’s case was traumatic, resulting from rupture of a mesenteric lymphatic vessel during D3 lymphadenectomy. This highlights the importance of meticulous surgical technique to avoid lymphatic fistulas; however, prevention remains difficult since lymphatic vessels are often not visible intraoperatively [9].

When chylous ascites occurs as a postoperative complication, it is considered early if it manifests within the first week, or late if due to adhesions or external compression of lymphatic vessels. Kaas et al. evaluated the incidence of chylous ascites in 1103 abdominal surgeries, finding 12 cases (1.1%), all in cancer patients. They reported that oncologic abdominal surgery complicated by chylous ascites occurred in 7.4% (12 of 163 cases), with retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy being the highest risk procedure identified [10].

Diagnostic paracentesis is the first-line tool, revealing alkaline pH, elevated triglycerides (150–1100 mg/dL), proteins (>3 g/L), and a predominance of lymphocytes (400–7000 cells ×10^3/μL). Cholesterol levels are usually low [11].

Imaging studies that assist diagnosis include abdominal ultrasound to detect fluid presence and abdominal CT to evaluate for retroperitoneal masses. Lymphoscintigraphy, the gold standard, visualizes lymphatic anatomy and leak site, providing both diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities through radioguided embolization. However, this technique is rarely available in many centers and is reserved for patients requiring surgical repair with precise leak localization [7, 12].

Both Kaas et al. and Aalami et al. reported that 67%–75% of chylous ascites cases resolve with conservative treatment [8, 10]. Thus, management focuses on three principles: maintaining or improving nutrition, reducing chyle production, and correcting underlying disorders [12, 13].

Therapeutic measures include oral fasting, medium-chain triglyceride diets, partial or total parenteral nutrition, and administration of somatostatin or its analogs, which reversibly inhibit gastric and pancreatic lipases to decrease fat absorption [9].

In refractory cases, more aggressive interventions such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts or surgery may be considered. If these fail, palliative repeated paracentesis is indicated [14, 15].

The objective of conservative treatment is to close the lymphatic leak, as multiple studies have shown high failure and recurrence rates with surgical treatment [16].

Our patient had multiple risk factors described in the literature, including surgical history and typical clinical and biochemical features of chylous ascites. The diagnosis was confirmed by characteristic ascitic fluid analysis and supplemented by imaging studies excluding other causes. Although lymphoscintigraphy remains the preferred diagnostic tool, it was not available in our setting.

Conservative management following abdominal fistula protocols was successful in this case. This report emphasizes that not all pathological conditions require surgical intervention; rather, clinicians should exhaust all available therapeutic options to provide less invasive, less aggressive care, as exemplified in this case of postoperative chylous ascites managed successfully with medical therapy.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, original draft preparation, review, and editing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

No financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.