-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Haris Sulejmani, Filip Vasilevski, Blagica Krsteska, Aneta Tanevska Zrmanovska, Nenad Mitreski, Andrej Nikolovski, Radiation-induced rectal leiomyosarcoma in a cervical cancer survivor: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf609, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf609

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Rectal leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is an exceptionally rare malignancy, representing ˂0.5% of all rectal cancers. Even more uncommon are the cases of radiation-induced LMS arising as an independent malignancy following pelvic radiotherapy. We report a case of a 56-year-old female patient with a history of high-grade large cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma treated 12 years earlier with radical hysterectomy and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The patient presented with rectal discomfort and altered bowel habits. A colonoscopy revealed a near-obstructing polypoid rectal mass, and a biopsy confirmed LMS. Surgical treatment via abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision was performed. Adjuvant chemotherapy was conducted by an oncologist. Given the long latency period and absence of metastases, the tumor was stated as a radiation-induced primary malignancy. This case emphasizes the importance of awareness in cancer survivors previously treated with pelvic radiotherapy and highlights the critical role of surgery in the management of rectal LMS.

Introduction

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) of the rectum is an exceptionally rare malignancy, accounting for ⁓0.1%–0.5% of all rectal cancers. This smooth muscle-derived tumor can occur throughout the body, though it most commonly arises in the retroperitoneum, uterus, and lower extremities [1, 2]. Although the etiology of rectal LMS generally is unclear, the association with previous pelvic radiotherapy (radiation-induced sarcoma) is reported [3]. We present a rare case of rectal LMS in a female patient previously treated with pelvic radiotherapy due to cervical cancer.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old female with a significant oncologic history presented with complaints of rectal discomfort, tenesmus, and altered bowel habits. Twelve years ago (in 2013) the patient had been diagnosed with large cell neuroendocrine cervical carcinoma, for which a radical hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed. Postoperative histopathological analysis confirmed a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor, staged FIGO IB2 (pT1B2 pN0 pMX G3 NG3). Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was applied (concurrent chemoradiation therapy and high dose rate boost brachytherapy) and remained in clinical remission for over a decade before presenting with the current symptoms.

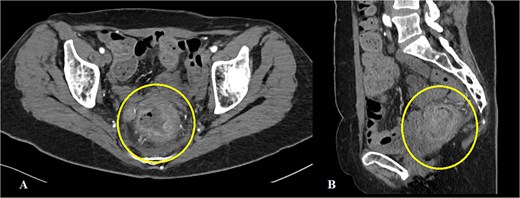

On a digital rectal examination an irregular, rectal mass was palpated. A colonoscopy revealed a large polypoid mass located ⁓5–7 cm from the anal verge, nearly occluding the rectal lumen and demonstrating surface necrosis. The obtained biopsies (standard hematoxylin/eosin stain and immunohistochemistry) confirmed the presence of rectal LMS. Preoperative laboratory findings showed mildly elevated inflammatory markers with a C-reactive protein of 56.4 mg/L and hemoglobin level of 113 g/L, with other parameters within normal range. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a rectal mass (Fig. 1A and B). The hospital’s oncologic board decision was to start the treatment with upfront surgery. The patient underwent an abdominoperineal rectal resection with total mesorectal excision. The postoperative course was uneventful. The length of hospital stay was 12 days.

Abdominal CT showing a mass in the rectum: (A) axial scan, (B) sagittal scan.

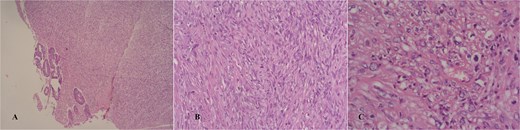

Macroscopically, the lesion measured 4.5 × 3.5 cm and partially encircled the anterior rectal wall (Fig. 2). Histologically, the tumor was composed of malignant mesenchymal cells arranged in a dense, solid pattern. Most of the cells exhibited a spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 3A–C), and scattered bizarre multinucleated cells were also observed. Mitotic activity was high, with up to 30 mitoses per 10 high-power fields. The tumor demonstrated extensive invasion through all rectal wall layers and had infiltrated the surrounding soft tissue.

Hematoxylin/eosin stain showing an infiltrative spindle cell neoplasm sparing the mucosa in a glance (A and B), high power field showing mild nuclear pleomorphism (C).

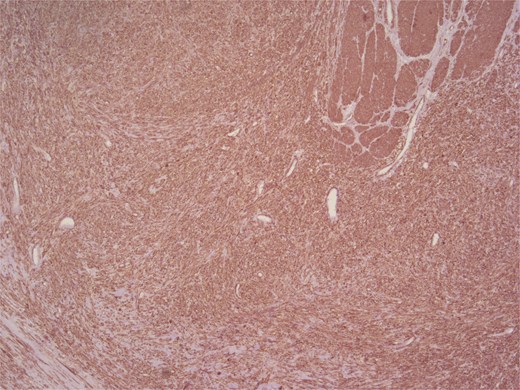

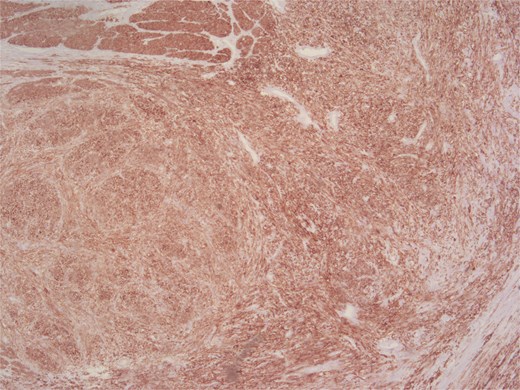

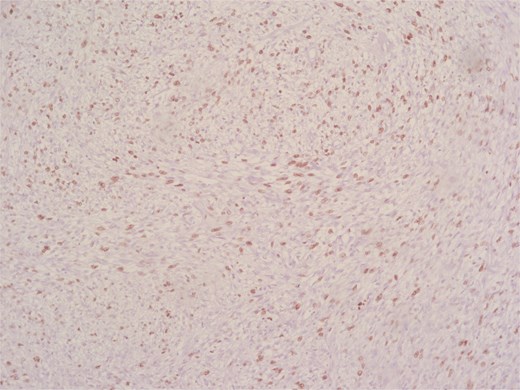

Immunohistochemical analysis supported the mesenchymal origin and confirmed a smooth muscle phenotype. The tumor cells demonstrated strong positivity for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Fig. 4) and desmin (Fig. 5), consistent with smooth muscle differentiation. CD117 (c-Kit) was inconclusive, while cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (CKAE1/AE3), SRY-related HMG-box gene 10 (SOX10), and cytokeratin 20 (CK20) were negative, helping exclude carcinoma, schwannoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. The Ki-67 proliferation index was markedly elevated, suggesting high proliferative activity (Fig. 6).

According to the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) grading system, the tumor was classified as Grade 2, with pathological staging according to the 8th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM classification as follows: pT1, pN1, Mx, R0.

The patient was referred to an oncologist, where adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and ifosfamide was initiated. A total of six cycles are planned as part of the postoperative treatment regimen.

Discussion

Rectal LMS represents an exceedingly rare clinical entity with only 300 reported cases [4]. Its pathogenesis, presentation, and optimal management remain incompletely defined. In a recent systematic review by Annicchiarico et al., only 31 cases of radiation-induced LMS of the rectum were identified in the literature, highlighting both its rarity and the increasing clinical significance among long-term cancer survivors exposed to pelvic radiation [5]. The association between pelvic radiotherapy and sarcoma development has been well-documented, particularly in female patients treated for gynecologic malignancies, such as cervical or endometrial cancer, as illustrated in the cases reported by Makhmudov et al. and Jayakumar et al., where rectal LMS developed 15–32 years after primary treatment with radiotherapy [3, 6].

Clinically, rectal LMS may present with nonspecific symptoms, including altered bowel habits, pain, or bleeding, although some cases remain asymptomatic and are incidentally discovered during routine surveillance or unrelated evaluations [7].

Radiologic imaging plays a key role in evaluating suspected rectal LMS. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are instrumental in local staging and surgical planning, although definitive diagnosis is only confirmed via histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation [3]. In some cases, the mass may not be distinguishable preoperatively from other pelvic lesions, such as recurrent cervical carcinoma, emphasizing the importance of biopsy and detailed immunophenotyping to rule out other malignancies, including gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), which is CD117 and DOG1 positive [8].

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment, intending to achieve negative margins. Radical approaches such as abdominoperineal resection or low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision (TME) are typically preferred, particularly in cases of low-lying or large lesions. The role of adjuvant therapy remains controversial, as neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy has demonstrated consistent benefit in reducing recurrence or improving survival for rectal LMS [5, 7]. A novel surgical strategy in challenging low rectal LMS cases has been the use of trans-anal total mesorectal excision (TaTME). Hoshino et al. reported the first use of a hybrid laparoscopic-TaTME approach for complete resection of a large anteriorly located LMS in the lower rectum, demonstrating its feasibility in achieving clear surgical margins even in anatomically constrained pelvic environments [9]. In this case, abdominoperineal resection was deemed the most appropriate upfront strategy due to tumor location and suspected invasion, aligning with the standard surgical principles described in the literature.

Histopathologically, LMS is characterized by spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended nuclei. High mitotic activity and necrosis are common poor prognostic indicators. Immunohistochemical positivity for smooth muscle actin, caldesmon, and desmin support the diagnosis, while negative staining for CD117 and DOG1 helps to exclude GIST [3, 5, 6].

This case adds to the limited growing body of literature on rectal LMS, particularly those arising after pelvic radiotherapy.

Conclusion

The current case represents a rare clinical scenario of a primary malignancy, a rectal LMS, occurring more than a decade after successful treatment of high-grade cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma. The long interval between diagnoses supports the interpretation of this lesion as an independent primary tumor rather than a late metastatic event. Rectal LMS are rare and aggressive malignancies with limited diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines. This case underscores the importance of considering LMS in the differential diagnosis of rectal masses, especially in patients with prior pelvic irradiation. Surgical resection with negative margins remains the mainstay of treatment. Continued reporting of such cases is essential to improve understanding and management of this rare entity. This case underscores the need for heightened surveillance in patients with prior pelvic irradiation, even decades after the treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

- radiation therapy

- biopsy

- leiomyosarcoma

- cancer

- cervical cancer

- colonoscopy

- defecation

- adjuvant chemotherapy

- immunologic adjuvants

- pharmaceutical adjuvants

- neoplasm metastasis

- neurosecretory systems

- surgical procedures, operative

- survivors

- neoplasms

- pelvis

- rectum

- rectal carcinoma

- radiochemotherapy

- hysterectomy, radical

- proctectomy, total

- mesorectal excision, total

- leiomyosarcoma, colonic

- rectal mass

- oncologists

- cancer survivors