-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdullah S Al-Darwish, Mohannad K Saffaf, Rime Bawareth, Sami AlHawassi, Intraperitoneal migration of an intrauterine device: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf579, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf579

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are a common and effective method of long-term contraception. However, rare complications such as uterine perforation and subsequent migration of the IUD to adjacent organs can occur. This case report describes a 29-year-old woman who presented with persistent abdominal pain and urinary symptoms secondary to IUD migration into the abdominal cavity, complicated by abscess formation. The case highlights the importance of considering IUD migration in patients with a history of IUD placement who present with abdominal or urinary complaints. It also underscores the need for routine post-insertion checks and thorough patient education to minimize risks.

Introduction

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are widely used worldwide due to their high contraceptive efficacy, long duration of action, and convenience [1]. Although generally safe, complications such as expulsion, pelvic inflammatory disease, and uterine perforation can occur [1, 2]. Uterine perforation, though rare (0.05%–0.2% of insertions), may result in IUD migration into the abdominal cavity and potential injury to adjacent organs [1, 3]. Clinical presentations range from asymptomatic cases to severe abdominal pain, urinary symptoms, or even life-threatening complications such as bowel perforation or obstruction [4, 5]. This report presents a rare instance of IUD migration leading to abscess formation and urinary tract symptoms, with emphasis on diagnostic approach, surgical management, and the necessity for appropriate follow-up care.

Case presentation

A 29-year-old multiparous woman with regular menstrual cycles presented to the outpatient clinic with a 6-month history of persistent, worsening lower abdominal pain accompanied by dysuria and urinary frequency. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

Five years earlier, she had an interval insertion of a copper T380A IUD (Cu-IUD) performed by a trained gynecologist consultant under local anesthesia at a gynecology clinic. She did not undergo routine post-insertion follow-up and reported that the IUD had never been checked or removed since its insertion. She denied any history of postpartum insertion, recent pelvic infections, fever, or abnormal vaginal discharge.

On physical examination, she was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Mild tenderness was noted in the lower abdomen without signs of peritonism. Pelvic examination showed no cervical motion tenderness or adnexal masses. The IUD strings were not visible on speculum examination.

Investigations

Initial laboratory work-up revealed a normal white blood cell count. Urinalysis was positive for leukocytes and nitrites, indicating a urinary tract infection. A plain abdominal X-ray did not clearly visualize the IUD but raised suspicion for its extrauterine location (Fig. 1).

A plain abdominal X-ray was performed, which visualize the IUD with suspicion for its extrauterine location.

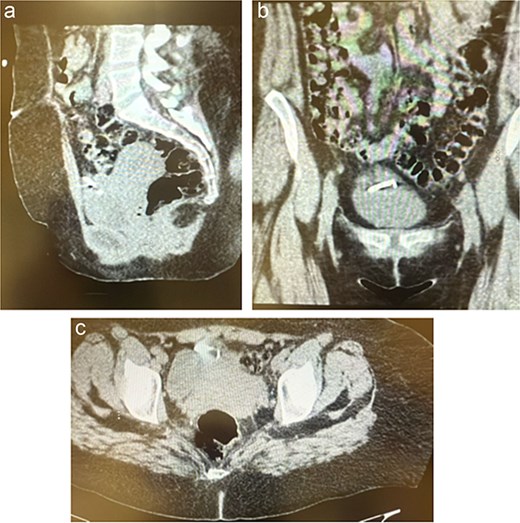

Given persistent symptoms and inconclusive plain radiography, an abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, revealing the IUD embedded in the anterior abdominal wall with an associated loculated fluid collection suggestive of a localized abscess (Fig. 2).

(a–c) The CT scan revealed the IUD embedded between the anterior abdominal wall and urinary bladder with a small, localized fluid collection suggestive of an abscess.

Diagnosis

Based on clinical and radiological findings, a diagnosis of IUD migration with an associated anterior abdominal wall abscess was made.

Treatment

The patient was admitted and commenced on intravenous piperacillin–tazobactam (4.5 g every 8 h) to treat the urinary tract infection and manage the intra-abdominal abscess.

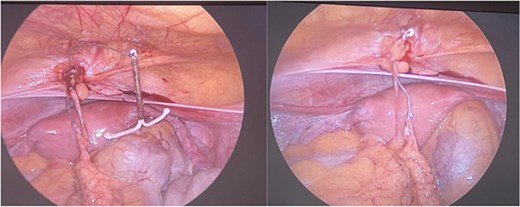

After 72 h of antibiotic therapy and clinical stabilization, she underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy. Intraoperative findings confirmed uterine perforation with the IUD partially embedded in the anterior abdominal wall amidst dense inflammatory adhesions and a localized abscess cavity. The IUD was carefully dissected free and removed. The abscess cavity was irrigated and drained thoroughly (Fig. 3).

Demonstrates the intraoperative findings during diagnostic laparoscopy. The IUD is visualized embedded in the anterior abdominal wall, surrounded by inflamed tissue consistent with a localized abscess. This confirms the diagnosis of uterine perforation and extrauterine migration of the IUD.

Postoperatively, she was transitioned to oral amoxicillin–clavulanic acid for an additional 7 days.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient’s recovery was uneventful. Her abdominal pain and urinary symptoms resolved completely. At her 1-month follow-up, she remained asymptomatic, with complete wound healing and no signs of residual infection. She was counselled on alternative contraceptive options and educated on the importance of routine follow-up for any future contraceptive device.

Discussion

IUD migration is an uncommon but recognized complication of IUD use [3]. The incidence of uterine perforation ranges from 0.3 to 2.6 per 1000 insertions for levonorgestrel IUDs and 0.3 to 2.2 per 1000 insertions for copper IUDs [1]. Risk factors include insertion during the postpartum period, inexperience of the provider, and pre-existing uterine anomalies [1, 6]. In this case, the lack of routine post-insertion surveillance likely contributed to delayed recognition and subsequent complications [7].

Clinical presentation can vary significantly, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe abdominal or urinary complaints [4, 8]. Migration may result in serious complications such as abscess formation, bowel obstruction, or organ perforation [3, 9]. Migration into the bladder can also cause stone formation [10, 11].

Diagnosis relies on imaging studies. Ultrasound is typically the first-line modality but may fail to detect extrauterine IUDs [1, 5]. Plain abdominal X-rays can help, but CT scans provide better visualization and can identify associated complications [5, 12].

Surgical removal is generally indicated to prevent further complications [1, 13]. Laparoscopy is usually preferred due to its minimally invasive nature and favorable recovery profile [5, 12]. However, laparotomy may be required for complex cases involving dense adhesions or visceral injury [5, 13].

This case highlights the need for clinicians to consider IUD migration when evaluating women with unexplained lower abdominal or urinary symptoms and a history of IUD placement. Patients should be advised about potential signs of migration and the need for prompt medical evaluation if symptoms arise [4, 7].

Conclusion

IUD migration, while rare, can cause significant morbidity if undetected. This case demonstrates that migration can lead to abdominal pain, urinary symptoms, and abscess formation. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical management are vital to prevent further complications. Routine post-insertion follow-up and patient education remain crucial for safe and effective use of IUDs.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.