-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Allyson Whitsett, Vincent Marcucci, Glenn Parker, Harnessing immunotherapy in sporadic MSI-H/dMMR colorectal cancer: a case study, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf576, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf576

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prevalent malignancy, with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) tumors representing a distinct, immunogenic subset. These tumors respond poorly to conventional chemotherapy but demonstrate favorable outcomes with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). We report the case of a 90-year-old male with severe anemia and a newly diagnosed sporadic MSI-H/dMMR CRC characterized by poorly differentiated, mucinous, and signet ring cell features. Molecular profiling revealed MLH1/PMS2 loss and MLH1 promoter hypermethylation. Despite his advanced age and multiple comorbidities, the patient underwent surgical resection followed by referral for ICI therapy in lieu of cytotoxic chemotherapy. This case highlights the importance of molecular testing in guiding treatment decisions and supports the consideration of ICIs in select elderly patients. It emphasizes that age alone should not preclude the use of effective, personalized therapies in CRC, particularly in those with good functional status and biomarkers predictive of immunotherapy response.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1, 2]. While the majority of CRC cases arise sporadically, a subset of tumors exhibits microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or deficient mismatch repair (dMMR), a molecular phenotype characterized by impaired DNA repair mechanisms leading to high mutation burdens and increased neoantigen presentation [3]. MSI-H/dMMR colorectal cancers account for ~15% of non-metastatic CRC cases and 5% of metastatic cases, with implications for prognosis and treatment response [4].

Historically, systemic chemotherapy has been the mainstay of treatment for advanced CRC, but the emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors has transformed the therapeutic landscape for MSI-H/dMMR tumors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved pembrolizumab and nivolumab—both programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors—as first-line therapies for metastatic MSI-H/dMMR CRC, citing improved response rates and progression-free survival compared to conventional chemotherapy [5]. The effectiveness of immunotherapy in this subset of CRC is attributed to the high tumor mutational burden, which enhances immune system recognition and response [6].

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-H/dMMR CRC, their role in elderly patients, particularly those with extensive comorbidities, remains an area of clinical interest. This case report describes the diagnosis and management of a 90-year-old male with sporadic MSI-H/dMMR colorectal cancer, emphasizing the role of molecular profiling in guiding treatment decisions and the therapeutic potential of immune checkpoint blockade.

Case report

A 90-year-old male with a past medical history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, aortic stenosis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, anemia, and gallstones was admitted to medicine for severe anemia. He was sent to the emergency department after outpatient labs revealed a hemoglobin level of 5.1 (reference 12.6–17.4 g/L). His baseline hemoglobin was 12–13 but had previously dropped to 8–10 in 2022, at which time he tested stool occult positive. His last known hemoglobin from 1 year prior was 12.8. He received two units of packed red blood cells on admission, with a post-transfusion hemoglobin of 7.0. Additional labs showed a mean corpuscular volume of 73.2 (reference 80–100 fl), platelets of 136 000 (reference 150 000-400 000/μl), iron of 14 (50–170 μg/dl), and ferritin of 2.9 (30–300 ng/ml).

The patient denied hematochezia, melena or hematemesis but reported progressive dyspnea on exertion over the past year and mild, intermittent abdominal pain for the past 5 months. Around the onset of the abdominal pain, he noted a change in bowel habits with looser, dark brown stools. His gastroenterologist advised probiotics, which improved stool consistency but led to constipation, requiring stool softeners. Colonoscopy was considered at that time but not pursued. He denied significant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use but took 81 mg daily aspirin with no anticoagulation therapy. He had no history of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or colonoscopy. There was no family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer.

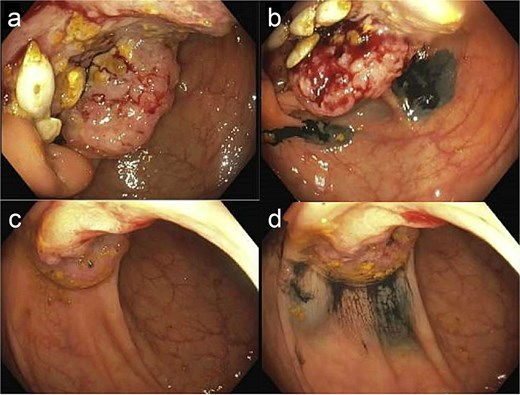

A digital rectal examination revealed external hemorrhoidal tissue but no gross blood, stool, or palpable lesions. Gastroenterology was consulted, and EGD revealed a 2 cm Hill grade II hiatal hernia, mild antral gastritis, duodenitis in the bulb, a small arteriovenous malformation in D3 and the bulb (cauterized), and a 4 mm lipoma in D3. Colonoscopy identified a large malignant cecal mass and a 2 cm apple core lesion in the hepatic flexure (both biopsied and tattooed), along with grade II internal and large external hemorrhoids (Fig. 1). Carcinoembryonic antigen value resulted as 23.9 (reference <3.0 ng/ml).

Colonoscopic imaging of cecal mass before biopsy/tattoo (a) and after (b). Colonoscopy imaging of hepatic flexure mass before biopsy/tattoo (c) and after (d). Note: Histologic or gross specimen images are not available for this case.

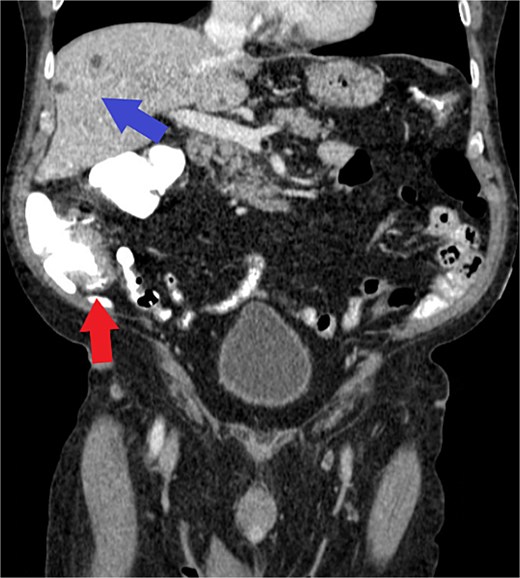

Computed tomography (CT) chest/abdomen/pelvis was ordered for staging. It showed focal wall thickening of the medial cecum, a 2.2 × 1.8 cm mesenteric lymph node in the right lower quadrant, and no evidence of metastatic liver disease (Fig. 2). A CT abdomen/pelvis from the previous year was used for comparison, showing multiple hepatic cysts, an enlarged prostate, and a left renal cyst, but an otherwise normal spleen, pancreas, bowel, and lymph nodes. Colorectal surgery was consulted, and the patient underwent a laparotomy and right hemicolectomy along oncological principles for a multifocal, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with mucinous, signet ring cell, and sarcomatoid features.

Axial view of CT demonstrating cecal wall thickening (red arrow) and benign hepatic cysts (blue arrow) without evidence of metastatic disease. Note: Histologic or gross specimen images are not available for this case.

The patient tolerated the procedure well and experienced no post-operative complications. At his 4-week outpatient follow-up, he reported no pain, was eating a regular diet, and had normal bowel movements. There was no clinical evidence of recurrence at that time.

Pathology revealed extensive lymphovascular invasion with metastases in 6 of 17 lymph nodes (pT4a, pN2a). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated loss of MLH1 and PMS2, and molecular analysis confirmed MLH1 promoter hypermethylation (70.2%), consistent with sporadic MSI-H CRC. Given the tumor's aggressive histology and MSI-H status, the patient was referred for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy instead of standard chemotherapy. Specific information regarding the agent, cycle count, or treatment tolerability is currently unavailable and represents a limitation of this report.

Discussion

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a significant global health concern, representing the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1, 2]. While most CRC cases are sporadic, ~15% of non-metastatic and 5% of metastatic CRCs exhibit microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) [3]. These tumors possess a distinct biological behavior, often characterized by high tumor mutational burden and enhanced neoantigen presentation, which contributes to increased immunogenicity [3].

Our patient’s tumor demonstrated classic features of MSI-H/dMMR colorectal cancer: a poorly differentiated, mucinous adenocarcinoma with signet ring cell and sarcomatoid features, located in the right colon, with loss of MLH1 and PMS2 expression due to MLH1 promoter hypermethylation. This molecular alteration is typically associated with sporadic, rather than hereditary, MSI-H CRC, and is most frequently observed in older adults and female patients [7].

The presence of MSI-H/dMMR in colorectal cancer has important therapeutic implications. These tumors tend to be resistant to conventional fluorouracil-based chemotherapy [5] but exhibit strong responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) due to their high neoantigen load and robust lymphocytic infiltration [6]. In particular, the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab have shown superior efficacy and tolerability compared to chemotherapy in metastatic MSI-H/dMMR CRC, leading to their FDA approval as first-line therapies in this population [7].

While immune checkpoint inhibitors are increasingly used in younger, fit patients with advanced MSI-H CRC, there remains limited data on their safety and efficacy in the elderly population, especially those with multiple comorbidities [8]. In this case, our patient, despite being 90 years old and medically complex, was deemed an appropriate candidate for immunotherapy given his good performance status, molecular tumor profile, and the potential morbidity associated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. The decision reflects a growing recognition that chronological age alone should not preclude aggressive, potentially life-prolonging treatment options in selected older adults [9].

This case also underscores the importance of timely molecular profiling in CRC. Delayed or missed identification of dMMR/MSI-H status can lead to suboptimal therapeutic decisions [10]. In older patients where CRC screening may have been deferred, as in this patient who had no prior colonoscopy, presenting symptoms such as anemia or changes in bowel habits warrant thorough evaluation [11]. Molecular characterization of resected tumors should be routine, as it informs both prognosis and the expanding landscape of precision medicine in CRC [12].

In summary, this case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic significance of MSI-H/dMMR status in CRC and highlights the potential for immune checkpoint inhibitors to offer a well-tolerated, effective alternative to chemotherapy even in nonagenarians. Future studies focused on elderly patients with MSI-H CRC are needed to better define optimal treatment strategies, balancing efficacy, quality of life, and individualized care [13].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.