-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lucky A Ehiagwina, Esteem Tagar, James Kpolugbo, Oseremen E Oigbochie, Axillary breast: our limited experience of surgical excision, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf536, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf536

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Axillary breast is a congenital anomaly of breast development that is often overlooked in surgical literature. It is commonly located in the axilla and can be misdiagnosed, especially if unilateral. It may present with or without pain and limitation of arm movement. We present three cases of painless axillary swellings. The first patient had a slowly growing swelling, the second experienced size changes related to hormones, and the third noticed a change during lactation. All had mobile, non-tender soft masses consistent with axillary breasts. The first two underwent surgical excision without complications, while the third opted for fine needle aspiration. Histopathological examination confirmed the presence of accessory breast tissues in all cases. This case series highlights the diagnostic challenges and management options for axillary breast, rare condition with similar pathological risks as normally positioned breast. Treatment options include non-operative care, liposuction or excision biopsy, with positive outcomes.

Introduction

An axillary breast is a rare congenital anomaly of breast development characterized by the presence of ectopic breast tissue (EBT). It results from the failure of involution of a portion of the mammary ridge. It has a reported incidence of 1%–2% in females and is twice common in females as in males [1, 2]. Accessory breasts are often asymptomatic, and often present as a visible swelling only, as observed in our patients. However, it may also present with pain, restricted arm movement, cosmetic concerns, malignancy risk related anxiety, and discomfort during menstruation, pregnancy, and lactation [1]. Ultrasonography and biopsy play crucial roles in diagnosing and managing these patients. Conservative management, liposuction or excisional biopsy, depending on the condition at presentation, often yield satisfactory outcomes.

We present three female patients with axillary breast with slightly different presentations. They did well after excisions.

Case 1

A 27-year-old Nigerian female presented to our clinic with swelling in the right axilla that had been present for 10 years (Fig. 1). The swelling gradually increased in size and was accompanied by discomfort. The swelling was not related to menstruation or pregnancy. She had no chronic cough, drenching night sweats, fever, anorexia, or weight loss and had no personal or family history of breast cancer. Clinical examination revealed a 6 × 4 cm soft, mobile, non-tender lobulated swelling in the right axilla. The overlying skin was normal, without any lesion or discoloration. Both breasts were normal on clinical examination. No other lesions in either axilla. The remaining physical examination was unremarkable. A provisional clinical diagnosis of axillary lipoma was considered. The differential diagnosis included axillary breast.

She underwent excisional biopsy (Figs 2 and 3) and histopathologic analysis revealed accessory breast tissue without malignant changes. The postoperative course was uncomplicated (Figs 4 and 5).

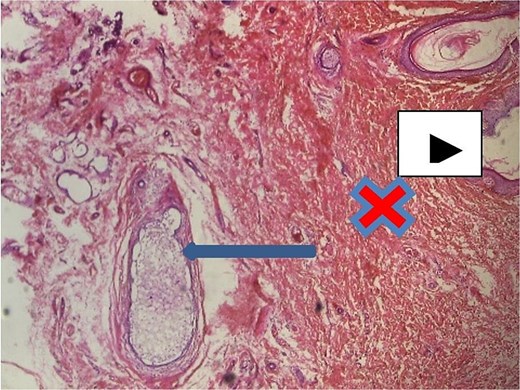

Axillary breast tissue ×40 magnification. Shows ectatic ducts containing secretions filled with foamy histiocytes (arrow), overlying skin epidermis (white arrow head) and interlobular stroma/dermis = red ‘X’ mark.

Case 2

A 30-year-old Nigerian female presented to our clinic with a 12-year history of pendulous swelling in the right axilla. It increased in size during menstruation, in the second trimester of her first pregnancy, and breastfeeding with some discomfort. There was associated milky discharge from the swelling (Figs 6 and 7) during lactation. She had no other complaints nor personal or family history of breast cancer.

Axillary breast showing milky discharge at presentation in the clinic.

Clinical examination revealed 9 × 7 cm swelling in the right axilla, along the milk line. It was soft, non-tender, not attached to underlying structures, and completely separated from the right breast. The overlying skin was normal, with evident milky discharge, but no nipple-areola complex was observed. Both breasts and the left axilla were normal on clinical examination. Other aspects of the physical examination were unremarkable. A diagnosis of right accessory axillary breast tissue was considered. Ultrasound of the axillary mass revealed a 7.0 × 6.1 cm space occupying lesion with well-defined margins, smooth contours, and heterogeneous hyperechoic internal echoes, consistent with breast tissue. It was not connected to the pectoral breast tissue. No cystic or solid mass lesions were observed. She underwent excisional biopsy, and histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of axillary breast tissue. The postoperative period was uneventful.

Case 3

A 66-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a complaint of painless swelling in the right axilla that was first noticed during her first pregnancy (Fig. 8) 40 years prior. It decreased in size after breastfeeding and has remained unchanged since then, with no associated discomfort. She had no personal or family history of breast cancer.

Clinical examination revealed 5 × 4 cm swelling in the right axilla. It was soft, mobile, non-tender, and separate from the right breast and underlying structures. The overlying skin was normal, without a nipple or areola. Both breasts and the left axilla were clinically normal. Other aspects of the physical examination were unremarkable. The clinical diagnosis was right axillary breast tissue. The differential diagnosis was axillary lipoma. She underwent fine needle aspiration cytology, which revealed accessory breast tissue without malignant changes (Fig. 6). She opted for a non-operative care after receiving the histology report.

Discussion

This case series presents an opportunity to discuss treatment options for axillary breast. Accessory breast (AB) is a rare condition, which affects 1%–2% of women and men. Occurrence rates vary widely by ethnicity and sex, ranging from 0.6% in Caucasians to 5% in Japanese women [3]. It is also known as polymastia, ectopic breast tissue, or supernumerary breast tissue. It results from the failure of involution of a portion of the mammary ridge. However, AB can develop outside the milk line in areas such as the lumbar region, vulva, perineum, and others. Therefore, alternative hypotheses have been proposed, including migratory arrest of primordial breast during chest wall development and development from modified apocrine sweat glands [4]. Axillary breast typically occurs sporadically, but a hereditary predisposition has also been reported [5, 6]. Our patients had no known hereditary predisposition, as there was no family history in any of them. In 1915, Kajava published a classification system for supernumerary breast tissue, which remains in use today. Class I consists of a complete breast with nipple, areola, and glandular tissue present. Class II consists of nipple and glandular tissue, but no areola is present. Class III consists of areola and glandular tissue, but no nipple is present. Class IV consists of glandular tissue only, without nipple or areolar tissue. Class V consists of the nipple and areola, but no glandular tissue (pseudomamma) is present. Class VI consists of only a nipple (polythelia). Class VII consists of only an areola (polythelia areolaris). Class VIII consists of only a patch of hair (polythelia pilosa) [7]. Our cases fall under classes I (there was none with nipple and areola) and IV.

AB is often asymptomatic, presenting as visible swelling only, as observed in two of our patients. However, it may also cause psychological distress during adolescence, pain, restricted arm movement, cosmetic concerns, anxiety related to risk of malignancy, and discomfort, particularly during menstruation, pregnancy, and lactation [1]. ABs can range from a subcutaneous focus of breast tissue to a full ectopic breast with nipples and areolas. The absence of the nipple-areolar complex can present a diagnostic challenge.

The clinical significance of polythelia and polymastia lies in the fact that in addition to their psychological and cosmetic impact, EBT is subject to the same hormonal influences and risks associated with normally positioned breast tissues, which can lead to similar pathological developments, such as inflammation, fibrosis, fibroadenoma, cystosarcoma phyllodes, and carcinoma [1, 8]. Therefore, individuals with EBT should undergo appropriate monitoring and evaluation. Moreover, patients with carcinoma arising from EBT often present late with a poor prognosis due to delayed diagnosis resulting from lack of awareness, misdiagnosis, atypical locations, delayed symptoms, and limited screening. Ectopic breast tissue may be misdiagnosed as benign conditions such as lipomas, cysts, or lymphadenopathy, leading to delays in accurate diagnosis [9]. However, two of our patients were diagnosed based on clinical evaluation since the masses were located along the milk linez in addition to the cyclical changes with the exception of one patient in whom axillary lipoma was considered, because of the absence of cyclical changes in the mass.

Additionally, patients with EBT may present with syndromic features such as pectoral muscle underdevelopment or midline developmental anomalies, which none of our patients had. EBT, particularly in polythelia cases, may also be associated with urinary abnormalities such as supernumerary kidneys, renal agenesis, polycystic kidney disease, duplicate renal arteries, ureteric stenosis, hydronephrosis and renal adenocarcinoma. This association can be partially attributed to the concurrent development of the mammary and genitourinary systems [10]. If EBT is suspected to be pathological, further investigations with fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), ultrasonogram, mammography, and biopsy should be performed, as for any other breast lesion [11].

EBT poses several challenges in routine breast cancer screening programs, including missed detection, lack of awareness, misinterpretation, and the absence of guidelines. Therefore, education and awareness are essential, along with clinical examination for EBT, and if present, patients should undergo routine screening alongside the normally positioned breast [12].

The treatment of EBT may be conservative or surgical. Conservative management may be suitable for asymptomatic patients, as shown in the third case report. Surgical options include liposuction or excision biopsy, or a combination of both. Accessory breast excision may be performed for diagnostic, therapeutic, or cosmetic reasons, as seen in the first case. Surgery is the definitive treatment for symptomatic patients [13].

In conclusion, the axillary accessory breast is a concern for women, particularly if it enlarges due to hormonal stimulation during menstrual cycle, pregnancy, or lactation. It can also pose a diagnostic challenge in patients with unilateral axillary swelling. Ultrasonography or excision biopsy, a safe procedure, may be necessary to achieve a definitive diagnosis and exclude potential malignancies. Conservative management may be suitable for asymptomatic patients.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.