-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessica A Nicholson, Mahmoud K Abd-El-Hafez, Andrew G Nicholson, Tanya J T Starr, Celeste M Murtha, Mark J Lieser, John M Chipko, A series of successful emergency department thoracotomies with expeditious recovery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf527, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf527

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Resuscitative thoracotomy is an invasive, morbid procedure indicated in the emergent management of blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest. It allows for rapid access to the thoracic cavity and treatment of the underlying pathology. Survival following traumatic cardiac injury relies on a near-impeccable combination of rapid assessment by properly trained emergency medical services personnel, rapid transport to a capable emergency center, accelerated access to the thoracic cavity within 10 min of cardiopulmonary resuscitation initiation, and excellent perioperative resuscitation. Overall survival rate following resuscitative thoracotomy in the United States is 9.6%. In addition, not all who survive make an acceptable neurocognitive recovery, with one large meta-analysis quoting only 92.4%. We report on two patients who survived and made a complete neurocognitive recovery following emergency department thoracotomy secondary to penetrating cardiac trauma. Both patients were discharged from the hospital within 16 days of their emergency department thoracotomy.

Introduction

An emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) is an invasive, highly morbid procedure indicated for the emergency management of blunt or penetrating trauma to the chest or abdomen. It allows for rapid access to the chest cavity for control of thoracic injuries or shunting of blood. Oftentimes, the primary goal is to restore spontaneous cardiac motion in order to perfuse critical organs [1]. Although the indications for this procedure continues to be highly discussed, it is primarily indicated for cardiac arrest due to penetrating trauma with recent signs of life or sustained hypotension caused by traumatic thoracic hemorrhage, cardiac tamponade, or systemic air embolism [2]. Success of the procedure is dependent upon rapid transport to a medical setting and early recognition of traumatic injuries (Gupta et al.). The Western Trauma Association deems emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) useless if no response is observed after 10 min of prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in cases of blunt chest injury, or after 15 min in penetrating ones [3].

EDT is a morbid procedure with a dismal survival rate. A 5-year analysis of 2229 patients who underwent EDT in the United States reported an overall survival rate of 9.6%. A 3% survival rate was associated with EDT following blunt trauma, while a 14% survival rate was associated with a penetrating mechanism [3]. In addition, not all who survive make an acceptable neurocognitive recovery. A large meta-analysis (n = 4620) reported that normal neurologic outcomes were observed in only 92.4% of patients surviving clamshell thoracotomy [4]. We present two patients who underwent successful resuscitative thoracotomies with subsequent expeditious and complete neurocognitive recovery. These cases highlight the importance of an accelerated assessment of a deteriorating patient and the ability to rapidly access the thoracic cavity for hemorrhage control.

Case 1

A 50-year-old male sustained a 2 cm stab wound above the right nipple following a domestic altercation. Glasgow coma score (GCS) was 13 as reported by the Emergency Medical Services (EMS). Upon arrival of EMS, patient was found to be in asystole and CPR was initiated for 4 min. Massive transfusion protocol (MTP) was activated. Intubation, a left anterolateral thoracotomy, and a right-sided thoracostomy tube was performed simultaneously. A large volume hemothorax and a pericardial laceration was visualized. Despite extension of the pericardotomy, the underlying cardiac injury could not be identified. Due to the ongoing high output of the thoracostomy tube and the need for better visualization, a clamshell extension (Fig. 1) was performed. Manual cardiac massage and intracardiac epinephrine was performed. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved. Two full thickness myocardial laceration underneath the right atrial appendage were identified following ROSC. The right coronary artery was spared. The lacerations were sutured with a 3–0 Prolene, in a figure-of-eight fashion. Patient was transferred to the operating theater where cardiothoracic surgery oversewn the wound with pledgeted prolene sutures. The remainder of the chest was explored and no further traumatic injuries were identified.

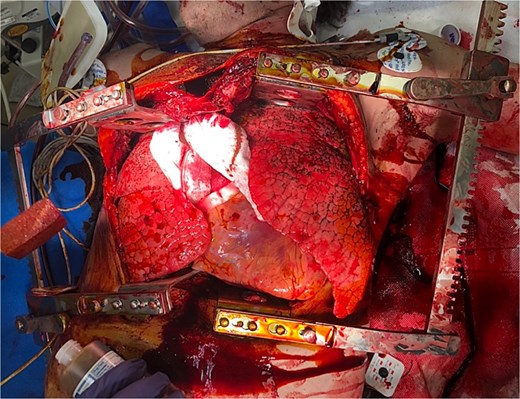

Clamshell thoracotomy in the ED for bilateral access to the thoracic cavity and mediastinum.

Patient remained hemodynamically stable but profoundly acidotic (lactic acid 8.0) during the operation. A total of four units of whole blood, twelve of packed red blood cells (pRBC), eight of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), one of platelets, and one of cryoprecipitate were administered during the perioperative resuscitative period, which was guided by thromboelastography. Postoperatively, echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 60%–65%. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 3 days given the nonsterile nature of the clamshell thoracotomy. Appropriate neurological recovery was appreciated on postoperative day (POD) 1. Patient underwent tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube placement on POD 4. By POD 11 patient was off ventilator support and tolerating PO intake. On POD 16, the tracheostomy was decannulated and the patient was deemed medically stable for discharge.

Case 2

A 28-year-old male presenting to the trauma bay following multiple gunshot wounds to the left chest and wrist. GCS was 7 per EMS. MTP was initiated prior to arrival. Patient was in obvious extremis with tachycardia (190 beats per minute) and hypotension (40/15 mmHg). Rapid-sequence intubation, right-sided central venous catheter, and left-sided thoracostomy tube were placed concomitantly. Shortly after the thoracostomy tube placement, which demonstrated a large volume hemothorax, patient developed asystole. A left anterolateral thoracotomy was performed showing obvious hemopericardium and tamponade. The pericardium was incised to release the tamponade and 500 mL of clotted blood was evacuated. A 2-cm myocardial defect was identified over the anterior aspect of the right ventricle. The laceration was closed with a 2–0 ethibond sutures, in a figure-of-eight fashion, and skin staples. Manual cardiac massage was initiated and a single dose of intracardiac epinephrine was administered. Spontaneous circulation was obtained in ˂5 min. Patient was transported to the operative theater for a formal repair by cardiothoracic surgery. The right ventricular wall was repaired via a median sternotomy and in a two-layer fashion using 4–0 pledgeted Prolene suture.

Estimated blood loss since arrival was 3 L. A total of one unit of whole blood, seven of pRBCs, seven of FFP, two of platelets, and two of cryoprecipitate were administered throughout the perioperative resuscitative period. A 7-day course of levetiracetam was initiated for witnessed tonic–clonic seizures. Patient was extubated on POD 1. Patient was off pressor medication and with a GCS of 15 by POD 2. Hospital course was complicated by COVID infection and patient was kept on prophylactic antibiotics. Postoperative echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction of 50%–55% with paradoxical interventricular septal motion, characteristic of the post-thoracotomy state. The patient was discharged with home health care on POD 14 following the resuscitative thoracotomy.

Discussion

Survival following traumatic cardiac injury relies on an expeditious primary survey and surgical intervention [5]. Robust research data suggests that survival following thoracotomy is favorable when the following factors are met: penetrating mechanism of injury, signs of life upon presentation to the hospital, GCS of 15, thoracotomy in the OR, rapid diagnosis and intervention, and age ˂60 years old [3, 6]. The rapid recovery of both patients detailed herein is likely attributed to the majority of factors mentioned above [7].

Mechanism of injury

Patients with penetrating cardiac injury and cardiac tamponade are the most likely to survive EDT [1]. The development of cardiac tamponade is often a positive prognostic indicator as tamponade delays bleeding from the cardiac lacerations [8]. The tamponade observed in both cases likely contributed to these patients’ positive outcomes. Considering all possible locations of major injury, survival rate is reported to be the highest, at 19.4%, when the heart is damaged versus abdominal injuries or injury to multiple visceral organs [4]. The survival rate following EDT is also reported to be higher following stab wounds rather than gunshot wounds [4, 9].

Presence of vital signs

Presence of vital signs during transportation corresponds to an 8.9% survival rate versus a 1.2%–2.6% rate among patients with a paucity of signs of life [4]. Signs of life were present in both cases detailed herein.

Rapid intervention

The Western Trauma Association has endorsed that clamshell thoracotomy is predisposed for poor outcomes when implemented in; penetrating thoracic trauma patients who received >15 min of CPR, blunt thoracic trauma patients who received >10 min of CPR, or penetrating extremity/neck trauma patients who received >5 min of CPR [2]. This is in comparison to the Eastern Association for the Surgery in Trauma, which endorse the efficacy of the ED thoracotomy when performed primarily in pulseless patients with signs of life following penetrating thoracic injury, where signs of life were defined as pupillary response, spontaneous ventilation, extremity movement, or cardiac electrical activity. In Case 1 the patient had only received 4 min of CPR following penetrating thoracic injury, well within the accepted window. The patient also had signs of life characterized by cardiac electrical activity on telemetry. In Case 2 no CPR was administered following his penetrating thoracic injury as patient did not have a loss of vitals until after arrival to the trauma bay. This patient also had signs of life on arrival including spontaneous extremity movement, spontaneous ventilation, and measurable/palpable systolic blood pressure.

Despite postoperative courses complicated by pneumonia and epileptic activity, both patients made an expeditious recovery, leaving the hospital only 16 and 14 days after admission, respectively. Molina et al. [9] reported a mean hospital stay of 22.4 days following clamshell thoracotomy for penetrating trauma. A more recent study reported a mean ICU length of stay of 24.1 days and a mean hospital length of stay of 43.9 days following resuscitative thoracotomy [10]. Comparatively, the patients detailed herein recovered quicker than the average patient undergoing thoracotomy.

Molina et al. [9] reported on 94 cases of penetrating cardiac injury treated with EDT. 16% survived the trauma bay, but only 8% survived until discharge. A more recent study reported that 71% of patients who survived until ICU admission ultimately passed [10]. Interestingly, Fitch et al. [10] found that 67% of deaths in the ICU following clamshell thoracotomy occurred within the first 24 h of admission. As such, the immediate period following EDT is critical and survival past the first day suggests a high likelihood of recovery. However, Fitch et al. [10] was unable to identify factors that play a role in the likelihood of survival once admitted to the ICU (including increasing age, injury severity score, body mass index, gender, ethnicity, EDT performed in the emergency department versus the operating room). Further research is needed to elucidate which factors may play a role in survival following ICU admission.

In conclusion, emergency department resuscitative thoracotomy is a morbid procedure that can be performed to save critically ill patients who have suffered penetrating injuries to the heart. It is recommended that this procedure only be performed in departments adequately equipped to handle such devastating traumatic injury. A near-impeccable combination of rapid assessment by properly trained EMS personnel, rapid transport to a capable emergency center, and accelerated access to the thoracic cavity with ˂10 min of CPR, as in our cases, increases the chance of patient survival. Adequate resuscitation in the perioperative period was also a critical portion in each of our patient’s hasty recoveries.

Acknowledgements

There are no personal financial disclosures, non-financial support, or conflict of interest to be acknowledged during the making of this case report. This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities. No external funding was obtained for the completion of this case report.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.