-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Devin M Davies, Mandalyn Mills, Repair of a gluteal Morel-Lavallee lesion with complex perineal laceration in a 44-year-old female: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 7, July 2025, rjaf483, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf483

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Morel-Lavallee lesions (MLL) are closed soft tissue degloving injuries that are primarily associated with high impact blunt trauma. The prognosis of MLL is dependent on a variety of factors, mainly severity and extent of other injuries. There is no current standard treatment protocol. There have been few reported cases of MLL with associated perineal lacerations. Here, we report a case of a 44-year-old female with a gluteal MLL with complex perineal laceration and anal laceration following a motor vehicle collision. The MLL was treated with open irrigation and placement of Jackson-Pratt drains in the subcutaneous space followed by repair of the extensive laceration. The patient’s post-operative course was complicated by wound dehiscence, and effectively treated with repeat debridement and local wound care. Our case details an approach for management and subsequent complication of this rare injury.

Introduction

A Morel-Lavallee lesion (MLL) is characterized by separation of deep fascia from the skin and superficial fascia [1, 2]. Currently, there are no standard guidelines in the management of these injuries [1]. Management depends on multiple factors such as size and severity [1]. Moreover, MLL presenting with perineal lacerations are rare, and management guidance is lacking for this combination of injury. We detail the management of a patient who presented to our emergency room with a combination of a gluteal MLL and perineal laceration.

Case report

A 44-year-old female presented after a motor vehicle collision with a perineal and gluteal injury. Primary survey noted a complex laceration of the right perineum with anal laceration extending caudally to the superior gluteal region. Remainder of the survey was negative with the exception for a right ankle sprain. Slow venous bleeding was noted without brisk arterial hemorrhage. A pressure dressing was placed. In the emergency room, she developed transient hypotension with systolic blood pressure in the 80’s that responded to 1 L of IV crystalloids without need for transfusion.

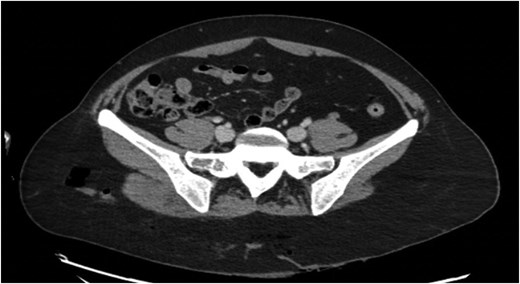

CT scan showed a perineal and gluteal laceration with concern for anal rupture, extensive subcutaneous emphysema of the right gluteal region (Fig. 1), and a small right subcutaneous hematoma. The patient was taken to the operating room for washout and repair.

Preoperative pelvic CT scan showing right gluteal subcutaneous emphysema.

The laceration extended from the poster fourchette of the vagina, caudally through the perineum to the anal mucosa, with partial disruption of the external anal sphincter. The wound extended caudally to the superomedial right gluteal cleft (Fig. 2). In total, the laceration measured 25 × 6 × 5 cm. An extensive subcutaneous flap consistent with MLL spanned 21 cm laterally over the right gluteus to the right iliac crest.

The subcutaneous space of the MLL was copiously irrigated with normal saline and Puracyn pulse lavage. Two 19 French Jackson-Pratt (JP) drains were placed in this subcutaneous space. Nonviable tissue was debrided. The gluteal aspect of the laceration was closed in layers. The subcutaneous tissue and deep dermis were closed with 3–0 vicryl sutures. The skin was closed to the level of the anoderm with vertical mattress nylon 2–0 sutures.

The laceration involving the perianal area and perineum was complex and extended down to the anal sphincter on the right. The external anal sphincter had an approximate 75% thickness laceration. Nonviable tissue was debrided and muscle fibers of the coccygeus and external sphincter were reapproximated by plicating with 3–0 vicryl sutures. The anal laceration was stellate involving nearly 50% of the circumference around the right side of the anal complex. The majority of the anal laceration was external to the anal canal but there was an approximate 1 cm laceration extending along the right lateral wall. Anal laceration and perineal laceration were first loosely reapproximated with 3–0 chromic sutures followed by running 3–0 chromic sutures. At the end of the case, prolapsed grade 4 internal hemorrhoids were observed secondary to edema. There were no rectal or vaginal defects other than what has been described.

Hospital course

The patient was admitted to the hospital for four days following surgery. Her hospital course was relatively unremarkable. She was on ceftriaxone and metronidazole while inpatient and did not show signs of infection. She started to ambulate on post-op day one with the assistance of therapies, and had bowel movements on post-op day two, albeit with mild incontinence that resolved within a week. JP drains were draining serosanguinous fluid. She was discharged on Augmentin 875 mg twice daily, topical bacitracin cream and JP drains in place (Fig. 3).

Wound at discharge on post-op day 4. Single prolapsed grade 4 internal hemorrhoid present.

Follow up

On first follow up appointment five days after discharge, the patient showed wound healing with improvement in pain and decreased output from JP drains. One drain was removed at this visit. On second follow up appointment one week later, the patient reported increasing pain along the gluteal wound edge. Wound dehiscence had occurred secondary to focal skin necrosis and infection, in which the patient was readmitted for antibiotics and wound debridement in the operating room. Along the right edge of the gluteal wound, there was an area of full thickness necrosis overlying the skin and subcutaneous tissue which was sharply excised. Some subcutaneous tunneling along the right lateral subcutaneous plane was observed, but the separated cavity layers of the MLL had started to adhere. After debridement, primary closure of the wound with placement of a 15 JP drain in the subcutaneous pocket was decided upon as the rest of the wound appeared healthy. Cultures of the wound showed scant growth of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus cloacae. The patient was discharged one day later on Augmentin 875 mg twice daily and topical bacitracin.

At subsequent follow up appoints the patient demonstrated excellent wound healing without signs of infection (Fig. 4). Two weeks after the take back procedure, drain output was 20–30 mL over 72 hours, at which point the drain was removed.

Discussion

MLL are closed soft tissue degloving injuries and their management is dependent on a variety of factors such as size, severity, and concurrent presenting injuries [1]. Currently, there is limited evidence supporting standard management guidelines [1]. Main treatment options include conservative treatment, percutaneous aspiration, sclerodesis, minimally invasive surgery, and open surgery [1, 3]. Moreover, MLL presenting with perineal lacerations may be associated with increase morbidity and mortality [4].

It has been observed that lesions with volumes greater than 50 mL drained by percutaneous aspiration have a greater chance of recurring and will likely require further procedures such as sclerodesis or open drainage [3, 5]. In our case of an MLL with an extensive subcutaneous space, immediate placement of drains allowed adherence without the need for procedures such as scerlodesis, thus far. Removal of the JP drain after the take back procedure when output was less than 20–30 mL over 72 hours has resulted in continued excellent wound healing, which aligns with other literature finding it reasonable to remove drains when output is less than 30 mL over 24 hours [6].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this study.