-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Leonardo V Coelho, Julio Y Konasugawa, Thiago Soares Coutinho, Gustavo Miranda Pires, Gustavo H Carillo Ambrosio, Paulo H S Lara, Management of a complex pelvic ring fracture in a polytrauma patient: a two-stage approach, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf368, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf368

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Unstable pelvic ring fractures, such as Tile C3, are high-energy injuries linked to polytrauma, with mortality rates up to 20%. A 30-year-old female presented with a bilateral unstable pelvic fracture, sacral fracture, left sacroiliac disruption, vaginal laceration, and mild pneumothorax after a truck-related accident (ISS 33). Following intensive care unit monitoring, a two-stage surgical approach was employed: anterior pelvic fixation and trans-sacral screw, then lumbopelvic fixation and sacroiliac screws after a 3-week delay due to material unavailability. Despite surgical challenges and delay, 18 months follow-up showed sustained improvements in function, psychological status, and quality of life. This case highlights polytrauma management complexity, surgical timing impacts, and multidisciplinary care’s role in favorable outcomes.

Introduction

Unstable pelvic ring fractures, such as those classified as Tile C3 [1], are high-energy injuries often associated with severe trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights. These fractures, when combined with visceral injuries like vaginal laceration, become even more challenging due to surgical complexity and high associated morbidity. The prevalence of unstable pelvic fractures ranges from 3% to 8% of trauma cases, with mortality rates reaching up to 20% in polytrauma scenarios [2]. This report describes the case of a young female patient with a bilateral unstable pelvic fracture and vaginal laceration following severe trauma, highlighting the challenges of clinical and surgical management in two stages, as well as the remarkably positive functional outcome.

Case report

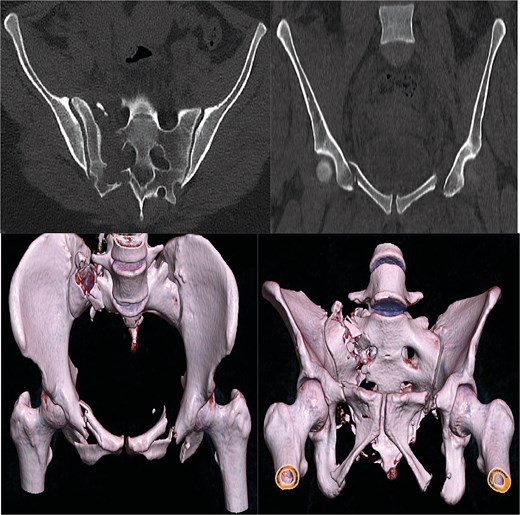

A 30-year-old female patient was admitted to the emergency department after falling from a truck and subsequently being run over by the same vehicle. Initial assessment revealed polytrauma with an unstable pelvic ring fracture and vaginal laceration, characterizing an open fracture. Imaging studies, including X-rays (Fig. 1) and computed tomography (Fig. 2), confirmed a Tile C3 fracture with bilateral vertical instability, classified as a lateral compression type III according to Young-Burgess [3]. Additional findings included a sacral fracture in Denis zone 2 on the right, disruption of the left sacroiliac joint, a mild right-sided pneumothorax, and a mild abdominal contusion. The vaginal laceration, ⁓5 cm in length, was successfully sutured by the gynecology team in the emergency room, with no immediate signs infection. The Injury Severity Score (ISS) was estimated at 33, reflecting the severity of the polytrauma (Table 1). Although hemodynamically stable, the patient was to the intensive care unit (ICU) for hemodynamic monitoring due to the risk of instability.

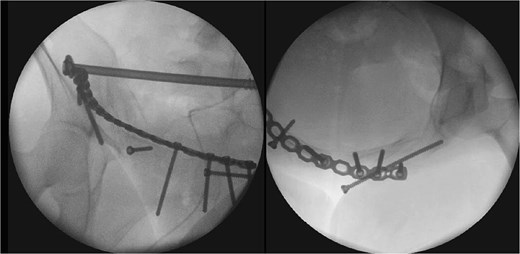

After one week of monitoring in the ICU, where she remained stable without need for ventilatory support, the patient was transferred to the ward. She then underwent the first surgical stage in supine position. Anterior pelvic fixation (Fig. 3a) was performed via a Pfannenstiel anterior approach combined with the first window of the right ilioinguinal approach, using a 3.5-mm reconstruction plate on the right anterior column crossing the pubic symphysis and a 3.5-mm retrograde screw in the left anterior column, inserted through the same Pfannenstiel access. During the same procedure, a 7.3-mm trans-sacral screw was placed in S1 on the right to stabilize the sacral fracture (Fig. 4). The surgery lasted ⁓3 h, and the patient was transferred to the semi-intensive care unit for postoperative monitoring.

| Injury Description . | Body Region . | AIS Score . |

|---|---|---|

| Severe Pelvic Fracture | Pelvis | 5 |

| Mild Pneumothorax | Thorax | 2 |

| Vaginal Laceration | Pelvis | 2 |

| Abdominal Contusion | Abdomen | 2 |

| TOTAL ISS* | 33 |

| Injury Description . | Body Region . | AIS Score . |

|---|---|---|

| Severe Pelvic Fracture | Pelvis | 5 |

| Mild Pneumothorax | Thorax | 2 |

| Vaginal Laceration | Pelvis | 2 |

| Abdominal Contusion | Abdomen | 2 |

| TOTAL ISS* | 33 |

*ISS = (52+22+22 = 25 + 4 + 4 = 33).

| Injury Description . | Body Region . | AIS Score . |

|---|---|---|

| Severe Pelvic Fracture | Pelvis | 5 |

| Mild Pneumothorax | Thorax | 2 |

| Vaginal Laceration | Pelvis | 2 |

| Abdominal Contusion | Abdomen | 2 |

| TOTAL ISS* | 33 |

| Injury Description . | Body Region . | AIS Score . |

|---|---|---|

| Severe Pelvic Fracture | Pelvis | 5 |

| Mild Pneumothorax | Thorax | 2 |

| Vaginal Laceration | Pelvis | 2 |

| Abdominal Contusion | Abdomen | 2 |

| TOTAL ISS* | 33 |

*ISS = (52+22+22 = 25 + 4 + 4 = 33).

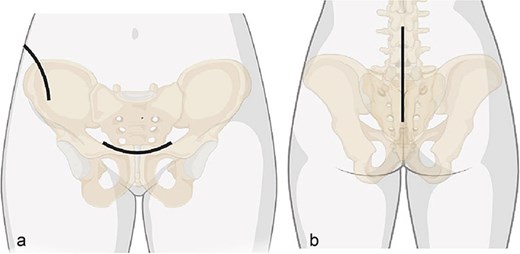

Surgical approaches diagram: (a) anterior approach; (b) posterior approach.

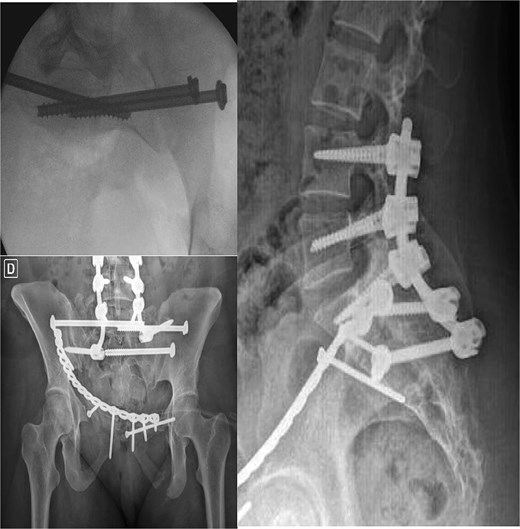

The second surgical stage was performed under general anesthesia two weeks later, delayed by one week of hemodynamic monitoring and subsequent unavailability of surgical materials. In supine position, the left sacroiliac joint was fixed with two 7.3-mm cannulated screws, and a seroma in the Pfannenstiel approach was drained. Subsequently, with the patient repositioned in prone position (Fig. 3b), lumbopelvic fixation from L4-L5-S1 to the posterior ilium (EIPS) was performed using rods and pedicle screws (Fig. 5). This procedure lasted ⁓3 h. At this point, ˃3 weeks post-trauma, anatomical reduction was significantly hindered by early consolidation and fibrosis at the fracture sites, requiring extensive maneuvers. The patient was transferred to the ICU, extubated without complications the following day, and returned to the ward after two days, receiving hospital discharge thereafter.

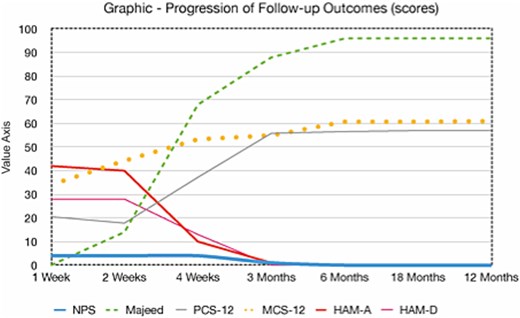

Follow-up assessments over 18 months showed sustained improvements in pain, function, quality of life, and psychological outcomes, detailed in Figs 6 and 7.

Discussion

Tile C3 pelvic fractures [1] feature vertical and rotational instability, often from high-energy trauma [4]. Combined with vaginal laceration, they increase infection risks, requiring multidisciplinary care [5]. Classified as Young-Burgess lateral compression type III [3], with Denis zone 2 sacral fracture and left sacroiliac disruption, the case showed severe compromise [6, 7]. A mild pneumothorax and abdominal contusion resulted in an ISS of 33 (Table 1) [8, 9].

The two-stage approach addressed initial severity (Fig. 3), using a Pfannenstiel and ilioinguinal approach for anterior fixation and an S1 trans-sacral screw for sacral stability [10, 11], followed by lumbopelvic fixation for posterior stability [12]. A 3-week delay, partly due to material unavailability, caused fibrosis, complicating reduction [13]. Seroma drainage in the second stage mitigated infection risks from the Pfannenstiel approach. ICU monitoring reflected management complexity despite stability [14]. Follow-ups over 18 months demonstrated functional recovery, quality-of-life gains, and psychological stability by 6 months, sustained to 18 months (Table 2, Fig. 7), despite early anxiety; this contrasts with studies linking severe psychological distress to poorer outcomes in Tile C fractures, suggesting early intervention mitigated these risks [5]. The Majeed score’s specificity, despite lacking a Portuguese version, and SF-12 supported outcomes analysis [15]. Pain assessment via the Numeric Pain Scale (NPS) revealed persistent lumbar pain radiating to right lower limb until the 4th week (NPS 4), resolving significantly by 3 months (NPS 1) and absent thereafter (Table 2, Fig. 7), consistent with rehabilitation progress and lumbopelvic fixation stability. This case underscores surgical timing challenges, the impact of delayed fixation, and multidisciplinary care’s value.

| NPS | Majeed | PCS-12 | MCS-12 | HAM-A | HAM-B | |

| 1 Week | 4 | 0 | 21 | 34 | 42 | 28 |

| 2 Weeks | 4 | 14 | 18 | 44 | 40 | 28 |

| 4 Weeks | 4 | 68 | 37 | 53 | 10 | 13 |

| 3 Months | 1 | 88 | 56 | 55 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| NPS | Majeed | PCS-12 | MCS-12 | HAM-A | HAM-B | |

| 1 Week | 4 | 0 | 21 | 34 | 42 | 28 |

| 2 Weeks | 4 | 14 | 18 | 44 | 40 | 28 |

| 4 Weeks | 4 | 68 | 37 | 53 | 10 | 13 |

| 3 Months | 1 | 88 | 56 | 55 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| NPS | Majeed | PCS-12 | MCS-12 | HAM-A | HAM-B | |

| 1 Week | 4 | 0 | 21 | 34 | 42 | 28 |

| 2 Weeks | 4 | 14 | 18 | 44 | 40 | 28 |

| 4 Weeks | 4 | 68 | 37 | 53 | 10 | 13 |

| 3 Months | 1 | 88 | 56 | 55 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| NPS | Majeed | PCS-12 | MCS-12 | HAM-A | HAM-B | |

| 1 Week | 4 | 0 | 21 | 34 | 42 | 28 |

| 2 Weeks | 4 | 14 | 18 | 44 | 40 | 28 |

| 4 Weeks | 4 | 68 | 37 | 53 | 10 | 13 |

| 3 Months | 1 | 88 | 56 | 55 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 Months | 0 | 96 | 57 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

Conclusion

This case illustrates the complexity of managing a Tile C3 pelvic fracture in a polytrauma patient. Despite a three-week delay, the two-stage surgical approach and multidisciplinary care resulted in sustained functional, psychological, and quality-of-life improvements over 18 months, emphasizing the critical role of timing and coordinated intervention.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None of the authors received (or will receive) payments or services, directly or indirectly from companies or scientific funding institutions to support any aspect of this work.