-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Caroline M Yang, Nestor Sabat, Ishanth Devinda Jayewardene, Case report: a case of foramen of Winslow hernia causing portal venous compression, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf357, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf357

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Foramen of Winslow hernias are a rare pathology that often have a delayed diagnosis and can lead to bowel obstruction and ischemia. We present a case of pre-operatively diagnosed foramen of Winslow hernia in a female in her 70s that presented with right upper quadrant pain. This involved herniation of the colon, causing transient portal venous compression. In this case it was managed operatively with a laparoscopic converted to open reduction of the herniated colon, with resolution of venocongestion post operatively.

Introduction

The foramen of Winslow hernia is a rare condition; it is a type of internal hernia involving herniation of another intra-abdominal organ through the epiploic foramen into the lesser sac. This most commonly involves the small bowel and less commonly colon [1]. There is often a delay in diagnosis, and a low rate of diagnosis pre-operatively (<10%) [2]. Patients may present secondary to symptoms from intestinal obstruction or have nonspecific pain [3–6].

Case report

A female in her 70s presented with acute onset of sharp stabbing right upper quadrant pain overnight. There was some migration of pain toward the epigastrium and umbilical region. She had been passing normal bowel movements every day. She has not had any vomiting or nausea. She did not have any fevers. She has a background of previous transvaginal pelvic prolapse repair surgery, but no other abdominal surgery. Her other medical history includes a previous mini-craniotomy for a subdural haematoma, osteoporosis, and depression. She is otherwise quite well and independent at home.

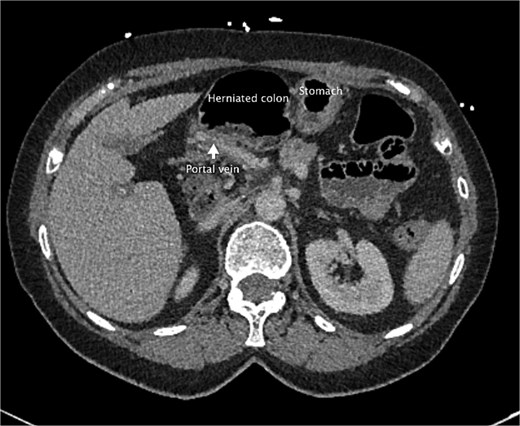

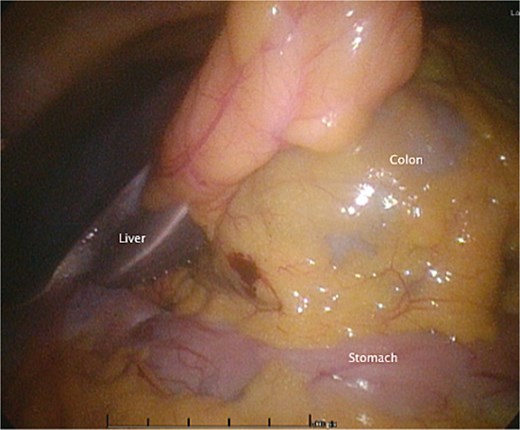

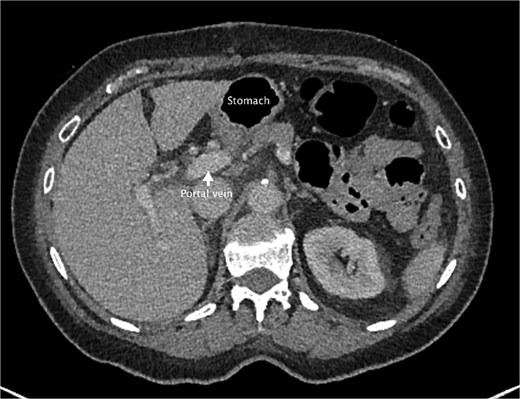

She had a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis in the emergency department, which was initially reported as mesenteric panniculitis. She had an initial lactate of 3.3 mmol/l (reference range < 2.0), other blood tests, including white cell count and hemoglobin level, were normal. C-reactive protein was also normal. She was referred to the surgical team in the morning to determine a follow-up plan as her pain had improved and she was planned to be discharged home. On review by the surgical team, she was clinically well, her abdomen was soft and not tender on examination. However, on review of the CT images, there appeared to be a dilated segment of colon in the right upper quadrant, and on further analysis, it appeared to be a Foramen of Winslow hernia containing colon. There was also an area that appeared to demonstrate a potential filling defect in the portal vein along with periportal oedema. This raised the concern of a potential thrombus versus vascular congestion (Figs 1 and 2).

An axial slice from the pre-operative CT abdomen pelvis in portal venous phase. There is an arrow pointing to narrowed appearance of portal vein. Also labeled are the herniated colon anteriorly and the stomach to the left of the herniated colon.

A coronal slice from the pre-operative CT abdomen pelvis in portal venous phase, with text labeling the herniated colon and differentiating this from the stomach.

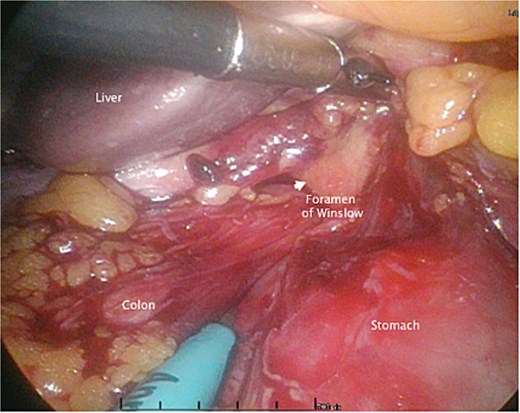

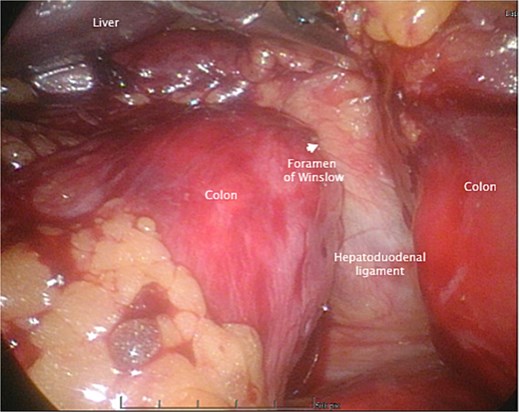

She underwent a laparoscopic converted to open adhesiolysis and reduction of internal hernia a few hours after surgical review. The surgery was commenced laparoscopically; adhesiolysis was performed to gain access to the colonic entry point through the epiploic foramen. Unfortunately, the contents of the hernia were not able to be reduced laparoscopically, given how dilated the colon was; there was a risk of perforating the bowel if further attempts were made. A decision was made to convert to laparotomy and an upper midline laparotomy incision was made. The colon was compressed manually and reduced. Inspection of colon showed a viable undamaged colon. The defect was not closed given preoperative review of current literature, and the fact that there are no reported recurrences of herniation postoperative reduction of contents [7, 8]. There was also a risk of damaging dilated colon with colopexy and there was minimal fat around hepatoduodenal ligament to allow closure to posterior edge of foramen. A washout was performed and transversus abdominis plane catheters were placed for pain relief bilaterally before wound closure (Figs 3–5).

An intraoperative photo during the initial laparoscopic part of the surgery, demonstrating the colon herniating through the foramen of Winslow.

An intraoperative photo during the initial laparoscopic part of the surgery, demonstrating the colon herniating through the foramen of Winslow.

An intraoperative photo during the initial laparoscopic part of the surgery, demonstrating the colon herniating through the foramen of Winslow.

Postoperatively, she was commenced on a free fluid diet. She had a repeat CT abdomen and pelvis with portal venous phase contrast on day 1 postoperatively to reassess portal system blood flow. It showed reduced periportal oedema and normal filling of the portal vein and splenic vein. Previous findings were favored to be vascular venous congestion from the internal hernia rather than thrombus formation. The repeat CT also demonstrated diffuse splenic hypoattenuation likely related to previous venous outflow obstruction and will likely resolve. Clinically, she progressed well postoperatively. She began passing flatus on day 2 postoperatively, bowels were open on day 5 after commencing a gentle osmotic laxative on day 4 after her operation. She was discharged home on day 5. She was followed up in the surgical outpatient clinic 4 weeks after her discharge. At this follow-up, she had been well since the operation, and no further intervention was required (Fig. 6).

An axial slice from the post-operative CT abdomen pelvis in portal venous phase. There is an arrow pointing to the portal vein that has returned to normal size. Also labeled is the stomach now lying anteriorly rather than the colon.

Discussion

Foramen of Winslow hernias make up about 8% of all internal hernias [9]. It should be considered as a potential cause for upper abdominal pain even without signs of obstruction, as in some patients, such as this patient, there were no signs of bowel obstruction clinically.

These hernias can also cause portal vein compression due to the location of the hernia, this has been identified as a feature that may help assist in the diagnosis of Foramen of Winslow hernias on CT [9]. In this case, there was a concern for whether there was also a thrombus formation in this region secondary to compression from the hernia, but fortunately, this was not the case. There was also mild splenic hypoattenuation postoperatively, likely secondary to the period of portal compression, causing a period of venocongestion, but this appeared to be mild and did not have further effects. In some cases, patients may have obstructive jaundice due to compression of the hepatic pedicle [2, 10].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.