-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ali Adwal Ali, Anmar Mohammed Ahmed, Sajjad Ghanim Al-Badri, Muntadher Yousif Hasan Al Gehadi, Nabeel Al-Fatlawi, Advanced squamous cell carcinoma with myiasis: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf263, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf263

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Advanced squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a challenge for treatment. It is also a risk factor for unintended infestation with Diptera larvae (maggots) known as myiasis. We describe a rare case of cutaneous myiasis located on a giant SCC of the face in an elderly female. Myiasis coupled with malignant skin conditions provides a unique surgical challenge as it is associated with a significantly increased risk of complications and mortalities. A literature review using PUBMED revealed 15 cases of SCC-associated myiasis due to different species. It is not only a disease of older age, as two of the patients were in their 20s. Pain, bleeding, and infection are possible symptoms due to infestation but not all patients reported complaints. Treatment aims to completely remove all maggots and to prevent secondary tissue damage with blindness due to eyeball destruction as one of the worst.

Introduction

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common non-melanoma skin cancer worldwide. Advanced tumors cause significant morbidity and mortality. SCC can spread using vascular and lymphatic route and perineural spaces. They infiltrate and destroy tissue thereby causing loss of function, pain, bleeding, and necrosis [1].

A rare association of advanced SCC is myiasis. Myiasis originated from the Greek term for fly (μÚγα). It is defined as infestation of the living (human) body by dipterous larvae (maggots) mainly from the suborder Calyptrate. Myiasis in SCC can be subdivided into wound myiasis and cavitary myiasis [2]. Many organs can be infested by fly larvae, but cutaneous and wound myiases are the most frequently encountered clinical forms [3]. Wound myiasis occurs when fly larvae infest an open wound on the host. Cutaneous myiasis has rarely been reported in skin tumors such as SCC. Large, ulcerated, necrotic, myiasis-burdened SCC lesions in the head and neck area present a challenge for treatment and to date, no consensus regarding first-aid management exists. In this report, a case of myiasis in a giant SCC in the face was managed.

Case presentation

A 100-year-old female with no significant medical or surgical history presented to the outpatient clinic at ‘hospital’ in Iraq, with a large, fungating, ulcerating, and discharging lesion on her right cheek. The lesion, accompanied by a large number of worms exiting from the wound, was noticed by the patient's family.

The patient's condition began 8 years prior as a small pigmented skin lesion, which was initially dismissed by the family as a benign mole related to aging. Four years later, the lesion enlarged, became slightly elevated and exhibited scaling. The family consulted a dermatologist, who suspected malignancy and recommended topical chemotherapy and excision, but the patient was non-compliant with treatment. Two years later, the lesion continued to grow, ulcerated with internal itching (Fig. 1), and became painful, prompting a visit to a surgeon who advised excision with a skin graft. This recommendation was also declined by the family, and the lesion continued to progress.

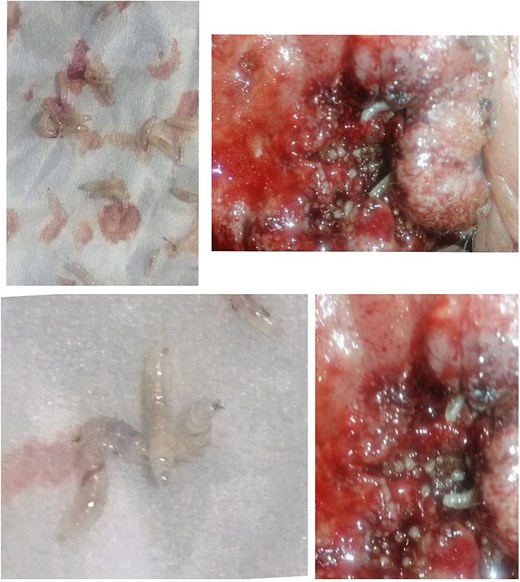

In the last 3 days prior to presentation, the family observed white worms emerging from the lesion (Fig. 2). The patient experienced significant pain, a decline in general well-being, and difficulty with oral intake and sleep. A nurse who provided wound care noted the presence of worms upon irrigation of the lesion, prompting the family to seek medical attention.

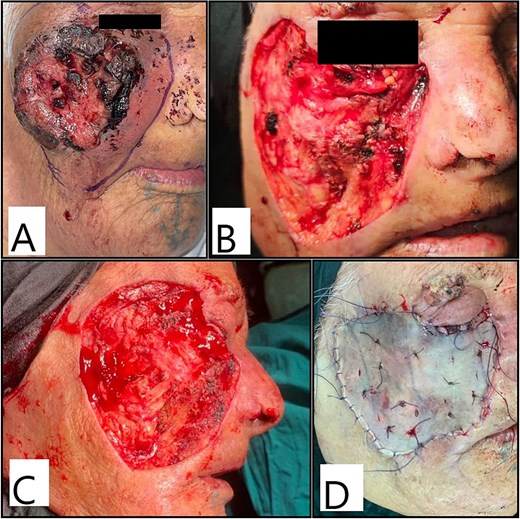

Upon examination at our clinic, the patient presented with a large erythematous, fungating, and ulcerating mass on the right cheek, measuring 12 cm in diameter, and round in shape, with areas of dark pigmentation, surrounding induration, and limited mobility. The lesion was minimally tender. Regional lymph node examination was unremarkable, and systemic examination revealed no abnormalities. The larvae were analyzed and found to be Diptera larvae (maggots). The lesion was diagnosed histopathologically as squamous cell carcinoma. Management includes; excision of the lesion with a safe margin and split skin graft application under local anesthesia either with or without copious sedation.

Intraoperative and post-operative photos are shown in Figs 3 and 4. The result of histopathology shows complete excision with free margin.

Intraoperative photos showing (A) marking of excision margins; (B, C) the resultant defect after excision and (D) after split-thickness skin graft application and fixation.

Discussion

SCC is the second most common skin cancer, accounting for 10% of all cases of skin cancer in the world, The clinical presentation of SCC is extremely variable, ranging from actinic keratosis, which is ubiquitously regarded as premalignant, to invasive SCC. Symptoms of invasive SCC include bleeding, weeping, pain, and tenderness around the lesion with persistent ulcers or non-healing wounds. SCC typically develops on sun-exposed skin, and ~55% of all cases of cutaneous SCC occur on the head and neck [3].

Myiasis is an infestation of the living human body by maggots. Myiasis is a possible complication of advanced and neglected SCC of skin. It has also been reported in oral SCC [4, 5].

Maggots or fly larvae can be separated into necrophagic, i.e. feeding from necrotic tissue only, and those who feed from vital tissue [6]. The latter are more painful and are commonly presenting as furuncular myiasis most caused by Dermatobia spp., Cordylobia spp., and Wohlfahrtia spp. [7]. The identified species in SCC patients were necrophagic (Lucilia spp.).

Wounds with alkaline discharge (pH 7.1 to 7.5) and the presence of necrosis are important indicators of wound myiasis [2]. When flies oviposit in necrotic, hemorrhaging, or pus-filled lesions, wound myiasis frequently occurs [2].

Dermatological symptoms of wound myiasis most commonly manifest as ulcers, and hyperkeratosis to a lesser extent [2]. Many dermatologic conditions, including neuropathic ulcers, psoriasis, seborrheic keratosis, onychomycosis, vascular insufficiency ulcers, cutaneous B cell lymphoma, and impetigo have all been reported to be associated with myiasis [2]. However, an association between myiasis and advanced SCC is rare, with only 15 cases reported in the literature [8].

Patients with myiasis in SCC lesions were characterized by the presence of advanced, giant, and neglected SCC skin lesions, poor social status, and comorbidities. Our case was like previous case reports, in that our patient presented with a giant SCC with an ulcer, necrotic tissue, crustation, and pain. Myiasis may have a significant negative effect on quality of life and outcome of such patients. Bleeding, pain, infection, and blindness have been reported [9–12]. Malodors are probably closer related to cancer necrosis than infestation, as maggots clean the wounds and produce antibacterial substances [13, 14].

Myiasis (Furuncular) has a mortality rate of up to 8% [2]. Early recognition and appropriate treatment will help to prevent these sorrowful events.

Treatment aims to remove maggots completely. The simplest measures are irrigation and mechanical removal. A review article stated that a 15% chloroform or ether in olive oil or another oil can be used to immobilize the larvae and facilitate maggot removal. Changing dressings consistently and daily is also required [2]. Vaseline and adhesive tape have been suggested to kill the maggot by asphyxia [15].

Topical treatment with 1% ivermectin in a propylene glycol solution applied directly to the affected body part and oral ivermectin (200 μg/kg) body weight are other options [2]. In some cases, surgery is necessary for infestations with C. Bezziana and C. Hominivorax, as cavernous lesions develop here [16].

In our case the maggots were removed with surgical excision of the lesion without any additional therapy.

Conclusion

Myiasis is a rare but serious complication of advanced SCC, particularly in neglected cases with extensive ulceration and necrosis. The presence of maggots can worsen morbidity, increasing pain, infection risk, and potential complications such as blindness. Although uncommon, early recognition and intervention are essential for improving outcomes. In our case, surgical excision was sufficient for complete removal without additional therapy. This highlights the need for timely diagnosis, proper wound care, and standardized management approaches to prevent and effectively treat SCC-associated myiasis.

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest to report.

Funding

No source of funding was received.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient family for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

Ethics approval

Our institution does not require ethical approval to report individual cases or case series.

References

Cavuşoglu T, Apan T, Eker E, et al.