-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Khaoula Nini, Zakaria Aziz, Divina Ndelafei, Houssam Ghazoui, Mohamed Salah Koussay Hattab, Nadia Mansouri Hattab, Solitary fibrous tumors of the infratemporal fossa: case series, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf338, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf338

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) were first described in the pleura. They are rare mesenchymal tumors of fibroblastic origin. An increasing number of SFTs has been described in the literature over the past years worldwide, particularly in the head and neck region, which is now considered the third most common site of occurrence. We report two cases of SFTs of the infratemporal fossa in two adult patients that were initially diagnosed as schwannomas on magnetic resonance imaging: one female patient with a small nodular lesion of the maxillary retromolar region and one male patient with a giant mass of the infratemporal fossa. Both cases were managed surgically using different approaches, achieving total excision of the masses. The first case has remained disease-free for four years postoperatively, while the second case is now at 1-year postop. To date, very few cases of SFTs in this region have been reported in Africa.

Introduction

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are rare spindle-cell neoplasms that were first described in 1931 in the lung and pleura but are now found throughout the body [1]. Head and neck SFTs account for 6%–18% of all SFTs [2]. The most frequently involved sites in the head and neck region are the oral cavity, orbit, infratemporal fossa, salivary glands, and sinonasal tract [3]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in both patients initially suggested schwannomas of the trigeminal nerve branches. CD34 and STAT6 markers are essential in confirming the diagnosis. In this paper, we describe two cases of SFTs of the infratemporal fossa treated at our institution.

Case reports

Case 1

A 23-year-old female patient with no medical history presented with gingival swelling of the retromaxillary and palatal gingiva that appeared two months prior and gradually increased in size. She reported no pain, teeth mobility, restriction of mouth opening, or numbness. Physical examination revealed a well-rounded red swelling of the right retromaxillary gingiva with telangiectasias, measuring approximately 1 cm in diameter, soft, and nontender. Mouth opening, sensitivity, and motility were normal. No lymph nodes were palpable, and the general examination was unremarkable (Fig. 1).

Facial MRI demonstrated a well-circumscribed retromaxillary tumor, hyperintense in T2-weighted images, initially diagnosed as a schwannoma (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation. A Dingman retractor was used to expose the retromaxillary lesion, followed by a mucosal incision and total excision of the tumor. Postoperative follow-up was uneventful, with excellent healing.

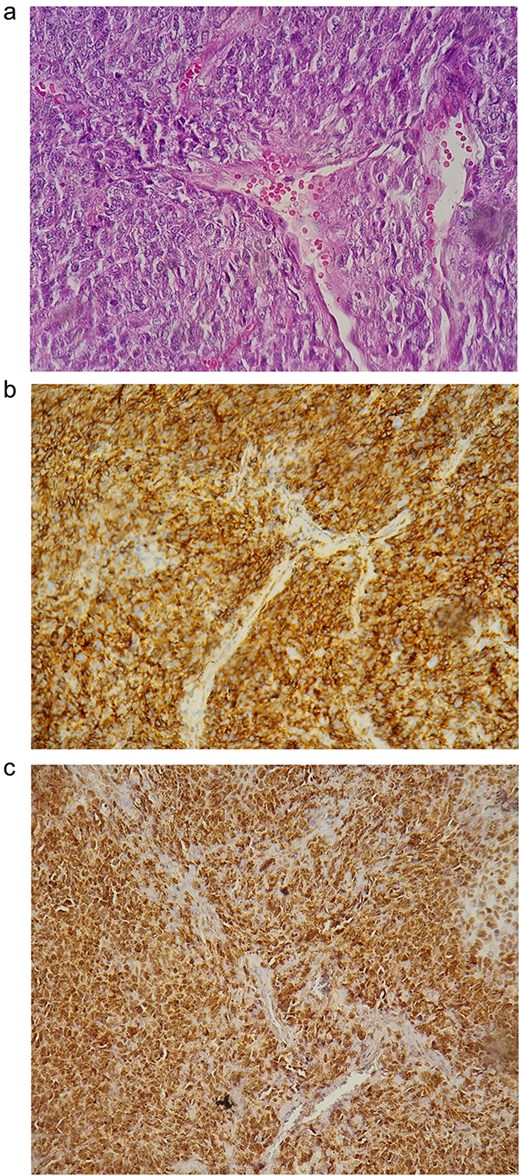

Pathological examination revealed oval to fusiform spindle cells with indistinct borders, arranged haphazardly or in short, ill-defined fascicles, along with dilated, branching, hyalinized staghorn-like (hemangiopericytoma-like) vasculature. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated positivity for STAT6, Bcl-2, and CD34 markers, confirming the diagnosis of a solitary fibrous tumor (Fig. 3). The patient remains recurrence-free four years postop.

(a) Histological findings; (b) positivity of the CD34 marker; (c) positivity of STAT6.

Case 2

A 58-year-old male patient with a history of cranial trauma two years prior presented with facial asymmetry due to left zygomaticomaxillary swelling associated with otalgia, tinnitus, and trigeminal neuralgia, progressively worsening over a year (Fig. 4). Physical examination revealed a smooth, fixed preauricular mass, round-shaped, regular, and nontender. The skin color was unchanged, and the exact tumor size was indeterminate. Sensitivity and motility were preserved. No lymph nodes were palpable, and the general examination was unremarkable.

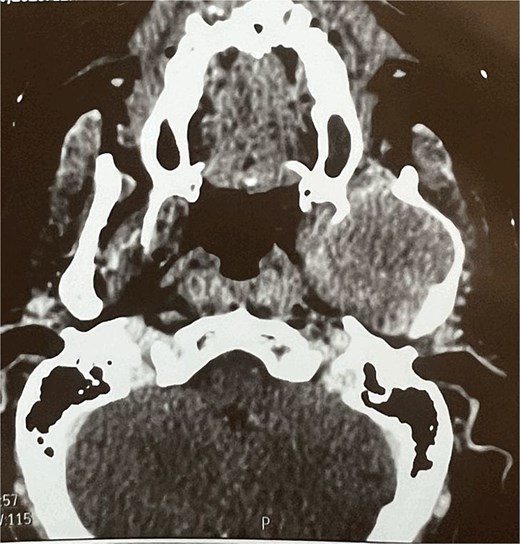

A facial CT scan shows a lesional process occupying the left infratemporal space, which is oval in shape, well-defined, and spontaneously isodense, with a calcified area and fine serpiginous vascular structures. It demonstrates heterogeneous enhancement after contrast injection (Fig. 5).

Facial MRI revealed a heterogenous soft tissue lesion in the infratemporal fossa measuring 47 × 51 × 53 mm, with imaging characteristics suggestive of a schwannoma of the third branch of the left trigeminal nerve.

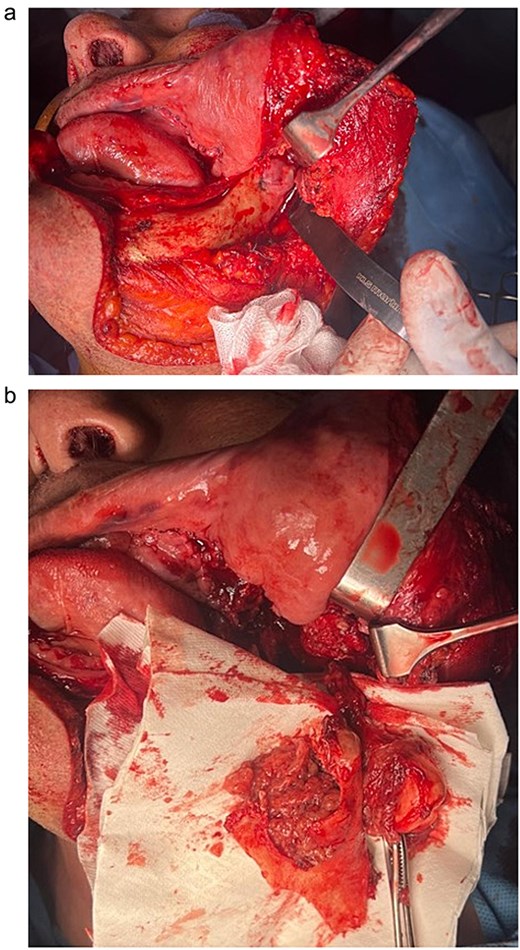

An initial biopsy was performed under general anesthesia via a preauricular transzygomatic approach. Pathological analysis favored a schwannoma. The patient was scheduled for tumor excision under general anesthesia. A transfacial transmandibular approach was performed, followed by a horizontal osteotomy of the ramus. Once accessed, the tumor was excised along with part of the posterior mandible (Fig. 6).

Intraoperative aspect of the tumor before excision (a) and after excision (b).

Postoperative follow-up was uneventful. Histopathological examination revealed a spindle cell mesenchymal tumor, with immunochemistry positive for STAT6, CD34, and SMA markers, confirming a solitary fibrous tumor with clear margins. No adjuvant therapy was required. The patient remains recurrence-free at 1-year postop.

Discussion

SFTs were first described in the pleura as a distinct submesothelial entity [4]. They are rare spindle-cell neoplasms of mesenchymal origin with an unknown etiology. Although they have been identified in various anatomical sites, the first reported case in the head and neck was in 1991 [5]. Head and neck SFTs account for approximately 10% of all SFTs [6].

The infratemporal fossa is an exceptionally rare site for head and neck SFTs [7]. Symptoms depend on tumor localization; in the infratemporal fossa, swelling and hypoesthesia due to trigeminal nerve compression are common. Paraneoplastic syndromes such as hypoglycemia (Doege–Potter syndrome) and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy have been described but were not observed in our patients [8].

Imaging findings lack specificity, often mimicking other soft tissue tumors. SFTs typically appear well-defined and vascular on CT and MRI [7]. In our cases, MRI findings were consistent with schwannomas, the primary differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors in this region.

Definitive diagnosis requires histopathological examination, characterized by spindle cells and “staghorn” vasculature. Immunohistochemical staining for STAT6 and CD34 confirms the diagnosis.

Complete surgical excision is the primary treatment for SFTs, as incomplete resection increases recurrence risk. Due to their deep location, access to the infratemporal fossa is challenging [9]. Various approaches exist, categorized as limited or extended. In our cases, a retromolar approach was used for the smaller tumor, while a transmandibular extended approach was necessary for the larger tumor.

SFTs have a generally favorable prognosis, with 5-year survival rates of 59%–100% and 10-year survival rates of 40%–89% [10]. Radiotherapy may be considered for positive margins, as SFTs are chemoresistant [11]. Emerging antiangiogenic therapies show promise but require further validation [10].

Close follow-up is crucial for early recurrence detection, with surveillance protocols tailored to individual patient characteristics [12].

In conclusion, SFTs of the infratemporal fossa are rare but should be recognized by maxillofacial surgeons. Due to nonspecific clinical and radiological findings, they may be misdiagnosed, delaying treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.