-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Simone Giungato, Concetta Lozito, Romana Palazzo, Camilla Dimito, Angelo Santo Pepe, Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for kissing duodenal ulcers spawned by refractory peptic ulcer disease: case report with technical note and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf327, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf327

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Peptic ulcer disease is a common condition that affects ~4 million people worldwide, according to a 1984 estimate. However, concomitant perforation of dual anterior and posterior ulcerations (so-called ‘kissing ulcers’) is rare and presents significant surgical challenges with high morbidity and mortality. Such scenarios present surgical challenges and impose very high-level morbidity and mortality. A 76-year-old man described herein required emergency treatment for duodenal peptic ulcer perforation. Overall, three operations took place in response to a single anterior peptic ulcer of duodenum that culminated in anterior/posterior kissing ulcers. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy was performed as a final attempt, along with radiographic localisation of the papilla. This rare instance of duodenal peptic ulceration underscores the feasibility and importance of a more definitive approach after ineffective initial surgical intervention.

Introduction

The epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) was detailed in a 1984 report [1], which estimated that approximately 4 million people worldwide are affected [2]. The annual incidence of duodenal ulcer perforation ranges from 3.77 to 14 cases per 100 000 persons [3], emphasising its substantial global impact. Despite advancements in treatment, PUD remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Within the vast spectrum of PUD complications, such as bleeding, penetration, and obstruction, perforation remains the second most common [4]. Perforated peptic ulcer (PPU) is a serious condition, with an overall reported mortality of 5%–25%, climbing to 50% as a function of age. The standardised 30-day mortality is 24.2% among patients 65–79 years of age and 44.6% among those ≥80 years old [5].

The introduction of proton pump inhibitors is credited for a decline in the incidence of perforated duodenal ulcer among Western countries, although mortality and morbidity remain high [6]. Concomitant anterior/posterior PPUs (so-called ‘kissing ulcers’) are quite rare, with very high morbidity and mortality attached to the difficult surgery entailed. Herein, we report an unusual case of kissing ulcers treated through pancreas-sparing duodenectomy.

Case report

A 76-year-old man with no known comorbidities presented to our Surgical Unit with an acute abdomen with pneumoleritoneum revealed on computed tomography. He immediately underwent exploratory xifo-umbilical laparotomy, demonstrating a 1.5-cm anterior duodenal wall perforation. Simple duodenal suturing was elected, leaving a subhepatic drainage tube in place.

On postoperative Day 8, 400 ml of biliary drainage and leakage of bile at the median laparotomy site again necessitated emergency laparotomy. The anterior duodenum could not be mobilised, so linear stapling was performed proximal to the ulcer beds. A gastrojejunal anastomosis was then created using transmesocolic Roux-en-Y reconstruction and duodenal sinking, and two drainage tubes were also positioned.

On Day 8 thereafter, the patient became septic. There was bile seeping from beneath the hepatic drainage line, with copious bile leakage at the median laparotomy site. Our expert upper gastrointestinal team was called upon for a third laparotomy, which then disclosed a second kissing ulcer posteriorly that penetrated anterior aspect of pancreas. Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy was carried out, resecting first and second parts of duodenum up to papilla of Vater. Unfortunately, the patient died 14 days later of pulmonary and cardiac complications.

Technical notes

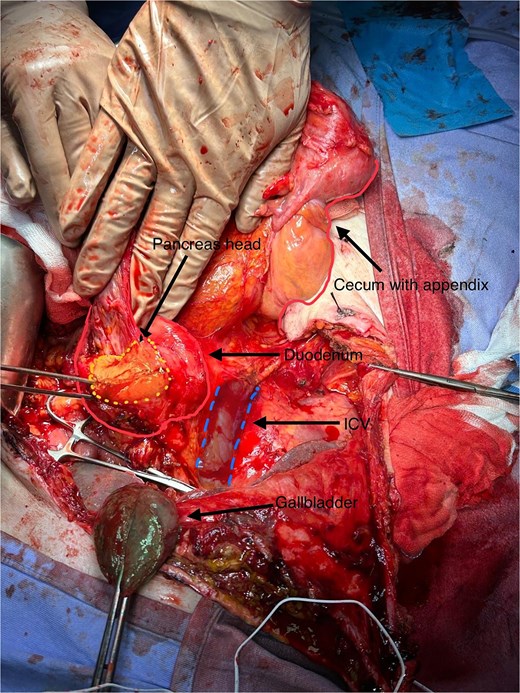

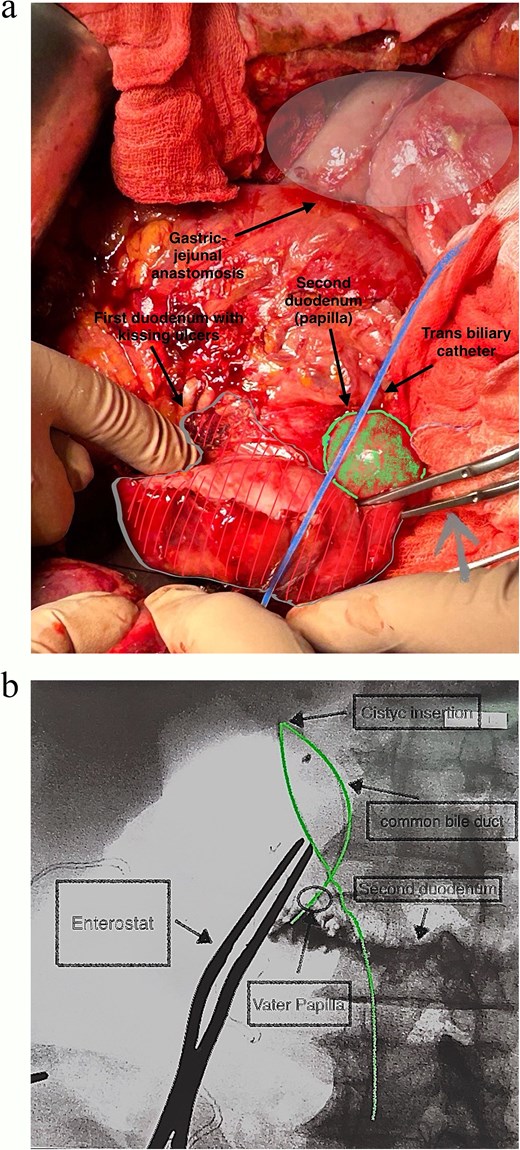

In this patient, median laparotomy was enabled by inverted-L incision, exposing a kissing ulcer during abdominal exploration (Fig. 1). Total mobilisation of ascending colon and caecum (Cattel-Braasch manoeuvre) and a complete Kocher manoeuvre were performed (Fig. 2). Cholecystectomy was also done with retention, thus serving for upper liver traction (Fig. 2). Once an enterostat was positioned just distal to the posterior peptic ulcer (Fig. 3a), a catheter was inserted through cystic duct to radiographically localise papilla of Vater during surgery. We injected contrast medium through the biliary catheter (with enterostat closed) to visualise the second and third parts of duodenum and confirm integrity of the papilla (Fig. 3b).

Anterior and posterior duodenal ulcers (arrows), each surrounded by yellow rim.

Total mobilisation of ascending colon and caecum (Cattel-Braasch manoeuvre) and complete Kocher manoeuvre, with inferior vena cava (IVC) and aorta exposed, leaving gallbladder in place for liver traction.

(a and b) Catheter placed within cystic duct to radiographically localise papilla of Vater during surgery, having positioned enterostat (grey arrow) immediately distal to posterior ulcer.

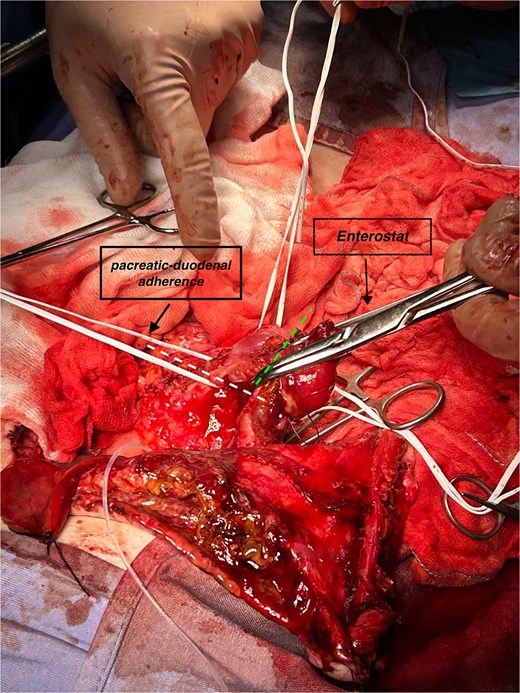

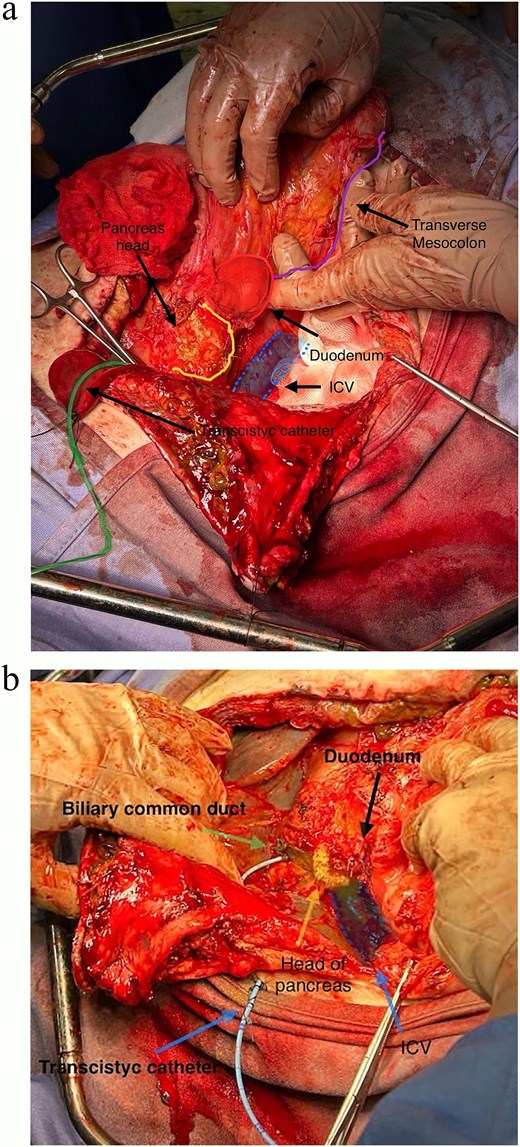

The vascular loop of duodenum and adherent pancreas was isolated to mark both duodenal sectioning planes (alongside head of pancreas and papilla) for linear stapling (Fig. 4). Duodenum was then detached from head of pancreas, common bile duct, and common hepatic artery (Fig. 5a and b). The transcystic catheter was left in place, and two drains were positioned in retroduodenal and pelvic space locations.

Focal pancreatic/duodenal adherence (loop in the left indicates section line) and duodenum proximal to papilla (other loop, sectioned at dashed line) before enterostat positioning.

(a and b) Completed pancreas-sparing duodenectomy, exposing head of pancreas, IVC and common bile duct (transcystic catheter retained).

Discussion

For patients with PUD, therapeutic options in the literature include the following: (i) conservative treatment, more recently detailed by Abdalgalil et al. [7]; (ii) direct suturing via laparoscopic means (with or without omental patch), as Kok et al. have depicted [8]; and (iii) conventional surgical treatment, as described by So et al. [9]. However, the various strategies proposed are regularly debated. There have been two clinical trials reported in 1983 and 2004 by Croft et al. and Songne et al. that show similar overall patient mortality, regardless of management approach (nonoperative vs operative) [10, 11]. Guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery advise primary direct repair (without omental patch) for PPUs and small perforations (<2 cm), while advocating intraoperative cholangiography for ulcers in proximity to ampulla of Vater [4].

The scenario described herein is a highly unusual circumstance (see Table 1). A search of principal scientific libraries (Pubmed, Google Scholar, Embase, and Cochrane Review) for keywords ‘emergency pancreas-sparing duodenectomy’ returned only 23 qualifying patients. Furthermore, ours is the first reported instance of pancreas-sparing duodenectomy for kissing ulcers. According to Krautz et al. [12], the above technique should be limited to high-volume hospitals, compelled by the refractory nature of duodenal ulcers. The present case is likewise quite unique with regard to observed morphologic manifestations, marked by a single anterior ulcer that progressed to kissing ulcers in the course of three operations.

Five published reports of pancreas-sparing duodenectomy procedures in 23 patients

| Pancreas-sparing duodenenectomy as an emergency procedure | Paluszkiewicz et al. | 5 | 2009 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in a patient with acute corrosive injury | Ramakrishnaiah et al. | 1 | 2013 |

| Pancreas-sparing ampulla preserving duodenectomy for major duodenal (D1–D2) perforations | Di Saverio et al. | 10 | 2018 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in the treatment of primary duodenal neoplasms and other situations with duodenal involvement | Busquets et al. | 6 | 2021 |

| Pancreas-sparing partial duodenectomy as an alternative to emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy for a major duodenal perforation: a case report | Wanabe et al. | 1 | 2023 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenenectomy as an emergency procedure | Paluszkiewicz et al. | 5 | 2009 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in a patient with acute corrosive injury | Ramakrishnaiah et al. | 1 | 2013 |

| Pancreas-sparing ampulla preserving duodenectomy for major duodenal (D1–D2) perforations | Di Saverio et al. | 10 | 2018 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in the treatment of primary duodenal neoplasms and other situations with duodenal involvement | Busquets et al. | 6 | 2021 |

| Pancreas-sparing partial duodenectomy as an alternative to emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy for a major duodenal perforation: a case report | Wanabe et al. | 1 | 2023 |

Five published reports of pancreas-sparing duodenectomy procedures in 23 patients

| Pancreas-sparing duodenenectomy as an emergency procedure | Paluszkiewicz et al. | 5 | 2009 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in a patient with acute corrosive injury | Ramakrishnaiah et al. | 1 | 2013 |

| Pancreas-sparing ampulla preserving duodenectomy for major duodenal (D1–D2) perforations | Di Saverio et al. | 10 | 2018 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in the treatment of primary duodenal neoplasms and other situations with duodenal involvement | Busquets et al. | 6 | 2021 |

| Pancreas-sparing partial duodenectomy as an alternative to emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy for a major duodenal perforation: a case report | Wanabe et al. | 1 | 2023 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenenectomy as an emergency procedure | Paluszkiewicz et al. | 5 | 2009 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in a patient with acute corrosive injury | Ramakrishnaiah et al. | 1 | 2013 |

| Pancreas-sparing ampulla preserving duodenectomy for major duodenal (D1–D2) perforations | Di Saverio et al. | 10 | 2018 |

| Pancreas-sparing duodenectomy in the treatment of primary duodenal neoplasms and other situations with duodenal involvement | Busquets et al. | 6 | 2021 |

| Pancreas-sparing partial duodenectomy as an alternative to emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy for a major duodenal perforation: a case report | Wanabe et al. | 1 | 2023 |

We have documented this particular case to illustrate the feasibility and necessity of duodenectomy after initial surgical setbacks in the setting of PUD. It is our opinion and one shared by others in the literature that sporadic scenarios of this sort warrant such procedures, using cholangiography to localise papilla of Vater for the benefit of less experienced surgeons. Duodenectomy performed during second-look surgery in our patient may have averted ensuing complications, improving his odds of survival.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.