-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rubén Daniel Pérez López, Juan Sánchez Lora, Ángel Ávila Rosales, Emmanuel Garcia Romero, Luis Rubén Sosa Flores, Beyond the ordinary: laparoscopic management of a rare inguinal hernia with bladder involvement, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf284, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf284

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inguinal hernias are common in surgical practice, with a small percentage involving bladder herniation. These inguinoscrotal bladder hernias, though rare, present significant diagnostic and treatment challenges. This case report details the diagnosis, treatment, and postoperative management of a 63-year-old male with benign prostatic hyperplasia, presenting with an inguinal hernia involving the bladder. Diagnosis was confirmed with physical examination and computed tomography scans, showing bladder herniation into the inguinal canal. Surgery involved laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair using a transabdominal preperitoneal approach. The surgery was successful with no complications and the patient was discharged 48 hours later. A three-month follow-up showed no recurrence or urinary complications. This case emphasizes the importance of considering inguinoscrotal bladder hernias in patients with inguinal bulges and urinary symptoms. Early diagnosis, supported by imaging and awareness, followed by laparoscopic repair, is essential for favorable outcomes in these rare cases.

Introduction

Inguinal hernias are a common condition in surgical practice, with a significant history of surgical management dating back to ancient times. While inguinal hernias are frequent, cases involving bladder entrapment known as inguinoscrotal bladder hernias are rare, comprising only 1%–4% of all inguinal hernias. First described by Levine in 1951 as a scrotal cystocele, these hernias are more common in older males with conditions that elevate intra-abdominal pressure.

This case report presents a 63-year-old male with an inguinal hernia involving the bladder, highlighting the diagnostic challenges and surgical interventions required. The aim of this report is to document and discuss the multidisciplinary approach and surgical techniques used, contributing to the understanding and management of this rare clinical entity.

Case report

A 63-year-old male with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia (diagnosed 2 years ago and currently treated with finasteride and tamsulosin) was admitted with a right inguinal bulge.

The bulge, first noticed five years ago, worsened during exertion and was associated with sharp pain and mild colic spasms. A week prior to admission, while lifting a heavy object, the bulge increased in size, and the patient experienced urinary symptoms (frequent urination, vesical tenesmus, dysuria) and acute pain, rated 9/10, accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

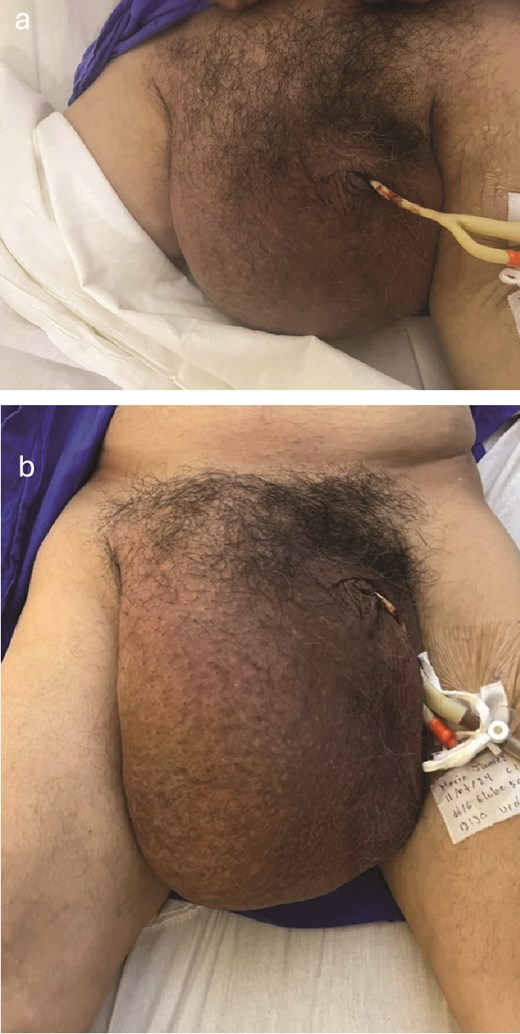

On admission, physical examination revealed a tense bulge (25 × 22 cm) in the right inguinal region, with moderate pain on palpation and no changes in coloration or temperature (Fig. 1a and b). Laboratory tests reported leukocytes 13.6 10 × 3/μL, neutrophils 88.9%, hemoglobin 14.1 g/dL, hematocrit 40.9%, platelets 344 000 10 × 3/μL, glucose 102 mg/dL, urea 147.7 mg/dL, creatinine 5.30 mg/dL, sodium 130 mmol/L, potassium 4.5 mmol/L, and arterial blood gas without alterations, lactate 1.2 mmol/L.

Clinical image of a bulge in the right inguinal region, approximately 25 × 22 cm in size, exacerbated by urine retention, without changes in coloration (a), and the same right inguinal bulge demonstrating how the size of the bulge increases with urine retention (b).

Imaging tests were performed, including a simple anteroposterior pelvic radiograph which showed a composite image with a radiopaque image in the inguinal region continuing caudally with well-defined, regular edges (Fig. 2).

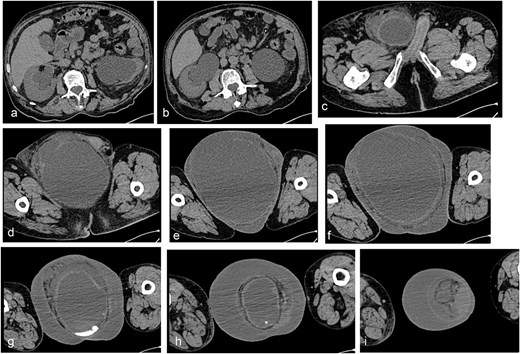

A non-contrast pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan was performed to evaluate a palpable right inguinal mass. The CT revealed an aponeurotic defect in the right inguinal region with protrusion of the urinary bladder into the right inguinal canal, completely lodging in the scrotal sac. This finding was associated with increased scrotal volume, striations of the periscrotal fat, and thickening of the scrotal wall by 25 mm. Significant dilation of the renal collecting system was also observed, measuring 40 mm on the right side and 62 mm on the left, with an increase in the diameter of the ureters. The bladder presented dimensions of 240 × 173 × 194 mm with a volume of 4212 mL, completely full and entirely located within the right scrotal sac. The findings indicate the presence of a right inguinoscrotal vesical hernia with bilateral dilation of the pelvicalyceal system, possibly exacerbated by maximum bladder filling (Fig. 3a–d, h, and i).

Simple abdominopelvic CT scan slices showing significant dilation of the renal collecting system, measuring 40 mm on the right side and 62 mm on the left, with an increase in the diameter of the ureters (a–c), an aponeurotic defect in the right inguinal region with protrusion of the urinary bladder into the inguinal canal (d–f), and the bladder completely full and entirely located within the right scrotal sac (g–i).

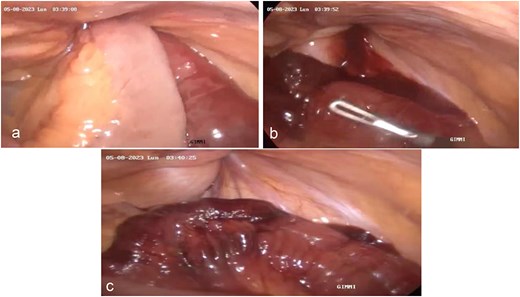

A urinary catheter was placed to reduce bladder volume. Given the urgency, emergency laparoscopic inguinal plasty with a transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach was performed. Under general anesthesia, a transumbilical incision was made for a 10 mm optical trocar, with two 5 mm parumbilical trocars inserted. During laparoscopy, the herniated bladder and a loop of ileum with vesical compression were observed at the deep inguinal ring (Fig. 4a and b). The loop was reduced by pulling the intestinal loop, and the bladder content was easily reduced (Fig. 4c).

Laparoscopic procedure for inguinal hernia repair using polypropylene mesh showing (a) visualization of the deep inguinal ring with herniated bladder content and ileum loop, (b) detail of marbled changes and inflammatory exudate on the intestinal loop, and (c) reduction of the herniated intestinal and bladder contents using traction without resistance.

The “critical view of safety” was used to dissect the myopectineal orifice. Peritoneal flaps were created 2 cm above the anterosuperior iliac spine, extending toward the umbilical ligament to access the Retzius and Bogros spaces, where the hernial sac was dissected. The dissection continued through the lateral, medial, and femoral triangle. A 12 × 15 cm polypropylene mesh was inserted, covering the myopectineal orifice and fixed with tackers, with peritoneal flaps closed using 2–0 Prolene sutures.

The postoperative course was favorable, with the patient tolerating oral intake 24 hours and being discharged 48 hours. Follow-up showed satisfactory healing, with a silicone-coated urinary catheter in place. At 6 months, adequate urine retention was observed, and the catheter was removed.

Discussion

Inguinal hernias have been recognized since ancient times, with surgical advancements in the 19th and 20th centuries [1]. Inguinal hernia with bladder involvement was first reported by Levine in 1951 as a scrotal cystocele [2].

Inguinal hernias are common, with a lifetime risk of 27% in men and 3% in women [3]. Hernias involving the bladder are rare, accounting for 1%–4% of inguinal hernias, particularly in older males with conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure [4]. Risk factors include male gender, advanced age, chronic urinary obstruction, weak pelvic musculature, and obesity [5].

Bladder hernias can be classified by bladder involvement and complications, such as urinary symptoms or obstructive uropathy. Inguinoscrotal bladder hernia can be subdivided into paraperitoneal, intraperitoneal, and extraperitoneal types [6].

Only 7% of inguinal bladder hernias are diagnosed preoperatively; most are diagnosed intraoperatively, with 16% diagnosed postoperatively due to complications like bladder injury [7].

In approximately 85% of cases, a noticeable bulge occurs in the groin area, worsening with standing or straining and reducing when lying down [1]. Pain is reported in 70% of cases, ranging from mild to severe, particularly during physical activities [3]. Urinary symptoms like frequent urination, incomplete emptying, and dysuria are common [4]. A palpable mass in the groin is detectable in 80% of patients, which may be reducible or irreducible. Obstructive uropathy, observed in 10% of cases, can lead to kidney issues and requires urgent attention [6].

Diagnosis is made through physical examination and imaging studies. Ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging is essential to confirm the bladder’s presence in the hernia sac and assess the hernia’s extent. In this case, CT imaging confirmed the bladder’s protrusion into the inguinal canal and scrotal sac, supporting the role of imaging in diagnosis. The presence of a bladder hernia does not change the surgical strategy. Treatment involves reintegrating the bladder into the abdominal cavity and repairing the defect. Laparoscopic repair was chosen in this case, demonstrating the effectiveness of minimally invasive techniques. Bladder resection is recommended only in cases of necrosis, bladder diverticulum, a narrow hernia neck, or a tumor in the herniated bladder [7].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest concerning the publication of this paper. The funding received does not influence the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (grant number AM02).

Consent

The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

References

Gould J. Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am 2008;