-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Renata Sonnenfeld, Gianmarco Balestra, Sandra Eckstein, Decision making in surgery: honoring patient autonomy despite high mortality risk in a 36-year-old woman with endocarditis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 3, March 2025, rjaf131, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf131

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a common complication in patients who inject drugs. We present the case of a 36-year-old woman with IE affecting both the aortic and tricuspid valves, along with a cardiac implantable electronic device infection, 11 weeks after combined aortic valve replacement, tricuspid valve replacement, and pacemaker implantation. The patient declined the medically indicated cardiac surgery due to her recent taxing surgical and rehabilitation experiences. Clear preoperative communication was crucial to align the patient’s goals with available treatment options. Decision making was achieved through multiple interdisciplinary discussions, fostering openness, and dialog. This case highlights the challenges of surgical decision making and provides a valuable example of a patient-centered approach to informed consent within a multidisciplinary team. Moreover, it demonstrates the successful integration of palliative care into surgical management.

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a common complication in intravenous drug users, associated with high morbidity and mortality [1]. One in 10 hospitalizations for endocarditis involves intravenous drug use [2]. Previous studies report a rising incidence of endocarditis in this population [2–4]. Depending on the infection’s severity and location, valve replacement surgery, along with antibiotic therapy, is often necessary [5].

Effective preoperative communication between surgeon and patient requires not only a thorough understanding of the case and a sound risk assessment but also the ability to align the patient’s goals with available treatment options [6–12].

Although surgical patients rarely receive palliative care, studies suggest that such interventions could greatly benefit patients, families, and healthcare providers, while reducing healthcare utilization without increasing mortality [12, 13].

We present a rare case of infective endocarditis in a young woman, where medical care and surgical consultation were complemented by palliative care involvement. This case highlights the challenges of surgical decision making and demonstrates a successful, patient-centered approach to informed consent within a multidisciplinary management framework.

Case report

A 36-year-old woman presented in July 2024 with a 2-day history of mild dyspnea, vertigo, and rapidly worsening general condition. She had a history of intravenous morphine use for over a decade but claimed to have been abstinent for several months. However, she was on a controlled oral morphine substitution, and her toxicological screening for opioids was positive. She was diagnosed with tricuspid valve endocarditis causing severe tricuspid insufficiency and aortic valve endocarditis with severe aortic insufficiency, both due to Staphylococcus aureus, leading to a thromboembolic stroke 11 weeks earlier (Videos 1 and 2). She required combined biological aortic valve replacement (AVR) and tricuspid valve replacement (TVR), along with epicardial DDD-pacemaker implantation (Implants: Inspiris Resilia, Epic Plus, Medtronic 4968, and St. Jude Endurity MRI). A bioprosthesis was preferred over a mechanical valve due to concerns about the patient’s adherence to lifelong anticoagulation therapy. The likely point of infection was cutaneous, due to recurrent skin ulcers and injection abscesses. A poor dental condition, present at the time of her native infective endocarditis and untreated due to non-adherence, was another potential source of infection. There was also suspicion of intravenous opioid use in addition to her prescribed treatment. Her medical history included chronic hepatitis and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (aADHD).

The patient presented to the emergency department with sepsis, meeting one major (positive blood culture) and two minor (fever, predisposition) Duke criteria. Blood tests revealed an elevated C-reactive protein of 289 mg/dl, while the leukocyte count remained normal. The blood culture PCR panel (GeneXpert) was positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as were all six blood culture bottles. She was immediately treated with empirical intravenous (IV) antibiotics (piperacillin/tazobactam), which were escalated to IV meropenem. When the antibiogram showed sensitivity to ceftazidime, the regimen was adjusted. However, due to persistent bacteremia, the antibiotics were expanded to include tobramycin.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no focus of infection or significant abnormalities.

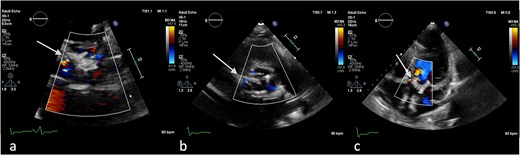

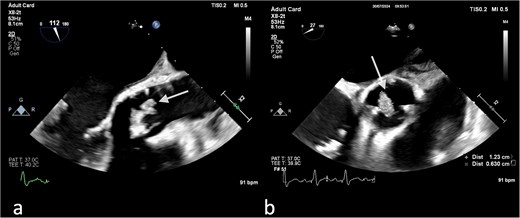

On the third day of hospitalization, transesophageal echocardiography revealed only moderate mitral regurgitation (Videos 3 and 4). However, on day 11, follow-up echocardiography showed a 7 × 18 mm vegetation on the prosthetic aortic valve, with a 5 × 7 mm floating formation (Fig. 2, Videos 5 and 6). By day 21, the vegetation had progressed, with a new formation on the tricuspid valve, an aortic annulus abscess, and worsened mitral regurgitation to severe (Figs 1 and 3, Videos 7 and 8). The development of double-sided endocarditis is very rare, and since the patient experienced it twice, congenital predisposing factors such as Patent Foramen Ovale and ventricular septal defects were ruled out. It was hypothesized that multiple predisposing factors ultimately led to the reinfection. Active IV drug use and its potential immunosuppressive effects, along with persistent poor dental condition and recurrent cutaneous infections, were identified as the main contributors, in addition to the patient’s overall non-adherence, for the development of double-sided endocarditis on two occasions.

Antero-septal paravalvular leak (PVL) of the prosthetic aortic valve in TTE (a) TTE PLAX (b), PSAX (c) 5CV (day 21 of hospitalization).

(a) Large vegetation on the neo-right coronary cusp of the aortic prosthetic valve in TEE LAX and (b) TEE SAX (day 11 of hospitalization).

(a) No vegetation, valve destruction of the prosthetic tricuspid valve on TTE RV inflow view, (b) No PVL of the prosthetic TV (TTE color doppler), (c) no signs of prosthetic IE on TV in TEE (day 21 of hospitalization).

Additionally, the patient received low-dose catecholamine therapy, IV fluids, and oxygen to stabilize hemodynamics. She improved with these interventions and, after four days in the ICU, was transferred to the medical ward.

The patient was informed that the only curative treatment option was a redo AVR and TVR. Her calculated EuroSCORE II was 17.94%. Furthermore, successful recovery also depended on intensive rehabilitation. She was hesitant to make a decision, feeling stressed and skeptical, especially due to the previous postoperative phase, which had been experienced as very stressful. The medical team decided to consult the ethics board, which included specialists from palliative care, cardiothoracic surgery, infectious disease, cardiology, and internal medicine. During the meeting, all treatment options, including palliative care, were re-evaluated. As a result, two options were agreed upon: curative cardiothoracic surgery or palliative treatment. These options were communicated to the patient and her family.

The patient declined surgery due to her previous experience with cardiothoracic surgery and the potential risk of reinfection after a redo. She consistently refused the procedure, fully aware that her decision carried a high risk of death. Regular palliative care rounds were held, along with roundtable discussions with the patient and her parents to ensure the consistency and clarity of her decision.

Throughout her hospitalization, the patient demonstrated sound judgment and remained consistent in her decision, expressing satisfaction with it. Seven days after the decision, she was transferred to a palliative care hospital. She continued intravenous ceftazidime therapy and received symptom-focused care. The primary goal was to allow the patient to spend her remaining time in a meaningful and self-determined way, while ensuring the best possible quality of life for both her and her family. Two weeks after the decision, the patient and her family expressed continued satisfaction with her choice and gratitude for the support they received.

Discussion

Recent studies show a 12-fold increase in IE-related hospitalizations among persons who inject drugs in the U.S. from 2007 to 2017 [14]. The mortality rate for hospitalized patients with IE is estimated at 15%–30% over the past two decades.

Palliative care in surgery was highlighted by the American College of Surgeons in 2003 to address the lack of research in this area (Table 1) [9]. The proposed agenda included decision making, symptom management, and surgical education about palliative care [9].

Seven priority areas for research adapted from the research agenda of the American College of Surgeon Palliative Care Workgroup 2003 [9].

| 1. Patient-oriented decision making |

| 2. Surgical decision making |

| 3. End-of-life decision making |

| 4. Symptom management |

| 5. Communication strategies |

| 6. Processes of care |

| 7. Surgical education about palliative care |

| 1. Patient-oriented decision making |

| 2. Surgical decision making |

| 3. End-of-life decision making |

| 4. Symptom management |

| 5. Communication strategies |

| 6. Processes of care |

| 7. Surgical education about palliative care |

Seven priority areas for research adapted from the research agenda of the American College of Surgeon Palliative Care Workgroup 2003 [9].

| 1. Patient-oriented decision making |

| 2. Surgical decision making |

| 3. End-of-life decision making |

| 4. Symptom management |

| 5. Communication strategies |

| 6. Processes of care |

| 7. Surgical education about palliative care |

| 1. Patient-oriented decision making |

| 2. Surgical decision making |

| 3. End-of-life decision making |

| 4. Symptom management |

| 5. Communication strategies |

| 6. Processes of care |

| 7. Surgical education about palliative care |

Lilley et al. found limited progress, with only 25 studies on palliative care for surgical patients from 1994 to 2014 [10]. Furthermore, in 2018, three key gaps in research were identified: measurement of patient-defined outcomes, communication and decision making, and implementation of palliative care in surgical patients (Table 2) [7]. In 2022, a review by Kopecky et al. echoed these findings, noting that research on integrating palliative care into surgery remains limited despite identified priorities [11].

Adapted from Lilley et al., priority areas from Palliative care in surgery: defining the research priorities [7].

| I. Measuring Outcomes that Matter to Patients |

|

|

| II. Communication and Decision Making |

|

|

|

| III. Delivery of Palliative Care to Surgical Patients |

|

|

|

| I. Measuring Outcomes that Matter to Patients |

|

|

| II. Communication and Decision Making |

|

|

|

| III. Delivery of Palliative Care to Surgical Patients |

|

|

|

Adapted from Lilley et al., priority areas from Palliative care in surgery: defining the research priorities [7].

| I. Measuring Outcomes that Matter to Patients |

|

|

| II. Communication and Decision Making |

|

|

|

| III. Delivery of Palliative Care to Surgical Patients |

|

|

|

| I. Measuring Outcomes that Matter to Patients |

|

|

| II. Communication and Decision Making |

|

|

|

| III. Delivery of Palliative Care to Surgical Patients |

|

|

|

Current literature shows that applying palliative care principles to surgical patients improves quality of life, reduces healthcare costs, and does not increase mortality [12, 13]. There is growing emphasis on integrating palliative care into surgical practice to ensure a patient-centered approach [7–11, 15].

A 2024 review by Angelos et al. highlighted the importance of patient-centered care and communication skills in surgical decision making, moving away from the paternalistic model [6–11].

Compared to previous case reports, the decision-making process was described as primarily dependent on the surgeon’s evaluation, considering mainly the overall risk and technical complexity of the procedure. It was often described how a high-risk operation was successfully performed on elderly or otherwise compromised patients [16, 17]. This case underscores the importance of preoperative communication and shared decision making. The cardiothoracic surgeon navigated the situation with trust and clarity, recognizing that decline of surgery should be considered, even in young patients without life-threatening comorbidities, if the personal recovery threshold is too high. In this case, involving palliative care ensured access to hospice care based on the patient’s values.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.