-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rajan Narayan Nakarmi, Bishal Budha, Roshan Chaudhary, Sushil Sah, Satish Bajracharya, Aashish Pandey, Valentino’s syndrome: diagnostic challenge of acute lower abdominal pain, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf934, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf934

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Acute lower abdominal pain poses a diagnostic challenge, with several potentially life-threatening causes. Although peptic ulcer perforation typically presents with upper abdominal pain, it can rarely mimic acute appendicitis—a phenomenon known as Valentino’s syndrome. We report a case from a resource-limited setting, where a patient presenting with right lower quadrant pain was initially diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Intraoperatively, the appendix appeared normal, but a purulent collection was noted in the right iliac fossa. Extending the incision revealed a perforated duodenum, confirming Valentino’s syndrome. This case highlights the importance of considering atypical presentations and maintaining a broad differential diagnosis in acute abdomen, particularly in resource-limited settings where preoperative imaging may be limited.

Introduction

Right lower quadrant abdominal pain is a frequent presentation in the emergency department, with a differential diagnosis that varies by age and gender. Common etiologies include acute appendicitis, perforated peptic ulcer, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, renal colic, ectopic pregnancy, dyspepsia, and urinary tract infection. Perforated peptic ulcer typically presents with right upper quadrant pain and carries significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly managed. A rare but important complication of peptic ulcer perforation is Valentino’s syndrome.

Valentino’s syndrome, a rare but lethal complication of peptic ulcer perforation, occurs when gastric or duodenal contents track along the right paracolic gutter to the right lower quadrant (RLQ), mimicking acute appendicitis [1, 2]. First recognized following Rudolph Valentino’s fatal case, its deceptive presentation often results in diagnostic delays and unnecessary surgery [3]. While imaging particularly computed tomography (CT) scan aid preoperative diagnosis, high clinical suspicion remains essential.

We report a recent case encountered in a resource-limited healthcare setting, highlighting the diagnostic, and management challenges of this uncommon presentation.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old male Army personnel, non-smoker, presented to the Emergency Department with severe pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen for the past 12 h. The pain was sudden, continuous, progressively worsening from 6/10 to 10/10 in intensity, piercing in nature, non-radiating, and non-migrating. It was not relieved by medications. He experienced two episodes of non-projectile, non-bilious, and non-blood-stained vomiting containing undigested food particles.

He had a past history of recurrent epigastric pain associated with water brash and heartburn, for which he intermittently used pantoprazole. He also reported frequent use of analgesics (Nimesulide and Aceclofenac) over the last 9 months for headache, low back pain, and foot pain. He occasionally consumes alcohol, with the last intake being 5 days prior to presentation.

At presentation to our Emergency Department, the patient appeared ill-looking, irritable, and diaphoretic. His blood pressure was 140/100 mmHg, pulse rate 112 beats per minute, temperature 100.8°F, respiratory rate 32 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. Abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen with localized tenderness in the right iliac fossa, associated with mild guarding. Rebound tenderness was elicited, and both Rovsing’s and Dunphy’s signs were positive. Examination of the other systems was unremarkable. With high suspicion of acute appendicitis, patient was kept nil per oral (NPO, started om intravenous fluid and intravenous antibiotics, and other supportive management. Hematological investigation revealed marked leukocytosis (16 200/mm3) with neutrophilic predominance of 88%. Renal function and electrolytes were within normal range, except for mildly low potassium (3.4 mmol/L) (Table 1). Liver function tests were essentially normal, with only a slightly raised alkaline phosphatase (206 U/L), which is non-specific. His serology was negative and ultrasonography confirm the clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis with localized inflammatory changes.

| Investigation . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 15.6 g% |

| Platelets | 204 000 |

| Total count/Differential count (TC/DC) | 16 200 (N88 L8 M2 E2) |

| Blood group | AB positive |

| Random blood sugar (RBS) | 146 mg/dL |

| PT/INR | 16 s / 1.09 |

| Urea/Creatinine | 26 / 1.1 mg/dL |

| Sodium/Potassium (Na/K) | 140/3.4 mmol/L |

| AST/ALT | 42/38 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 206 U/L |

| Bilirubin (Total/Direct) | 1.4/0.8 mg/dL |

| Gamma GT (GGT) | 32 U/L |

| Total protein | 5.2 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.8 g/dL |

| Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV)/Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/Hepatitis C virus (HCV) Ab | Negative |

| Urine routine/Microscopy | Within normal limits |

| Investigation . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 15.6 g% |

| Platelets | 204 000 |

| Total count/Differential count (TC/DC) | 16 200 (N88 L8 M2 E2) |

| Blood group | AB positive |

| Random blood sugar (RBS) | 146 mg/dL |

| PT/INR | 16 s / 1.09 |

| Urea/Creatinine | 26 / 1.1 mg/dL |

| Sodium/Potassium (Na/K) | 140/3.4 mmol/L |

| AST/ALT | 42/38 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 206 U/L |

| Bilirubin (Total/Direct) | 1.4/0.8 mg/dL |

| Gamma GT (GGT) | 32 U/L |

| Total protein | 5.2 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.8 g/dL |

| Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV)/Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/Hepatitis C virus (HCV) Ab | Negative |

| Urine routine/Microscopy | Within normal limits |

| Investigation . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 15.6 g% |

| Platelets | 204 000 |

| Total count/Differential count (TC/DC) | 16 200 (N88 L8 M2 E2) |

| Blood group | AB positive |

| Random blood sugar (RBS) | 146 mg/dL |

| PT/INR | 16 s / 1.09 |

| Urea/Creatinine | 26 / 1.1 mg/dL |

| Sodium/Potassium (Na/K) | 140/3.4 mmol/L |

| AST/ALT | 42/38 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 206 U/L |

| Bilirubin (Total/Direct) | 1.4/0.8 mg/dL |

| Gamma GT (GGT) | 32 U/L |

| Total protein | 5.2 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.8 g/dL |

| Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV)/Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/Hepatitis C virus (HCV) Ab | Negative |

| Urine routine/Microscopy | Within normal limits |

| Investigation . | Result . |

|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hb) | 15.6 g% |

| Platelets | 204 000 |

| Total count/Differential count (TC/DC) | 16 200 (N88 L8 M2 E2) |

| Blood group | AB positive |

| Random blood sugar (RBS) | 146 mg/dL |

| PT/INR | 16 s / 1.09 |

| Urea/Creatinine | 26 / 1.1 mg/dL |

| Sodium/Potassium (Na/K) | 140/3.4 mmol/L |

| AST/ALT | 42/38 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | 206 U/L |

| Bilirubin (Total/Direct) | 1.4/0.8 mg/dL |

| Gamma GT (GGT) | 32 U/L |

| Total protein | 5.2 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.8 g/dL |

| Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV)/Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/Hepatitis C virus (HCV) Ab | Negative |

| Urine routine/Microscopy | Within normal limits |

The Alvarado score was calculated to be 9 out of 10, with all parameters fulfilled except anorexia. After appropriate counseling and obtaining informed consent, the patient was taken to the operating theatre for an open appendectomy.

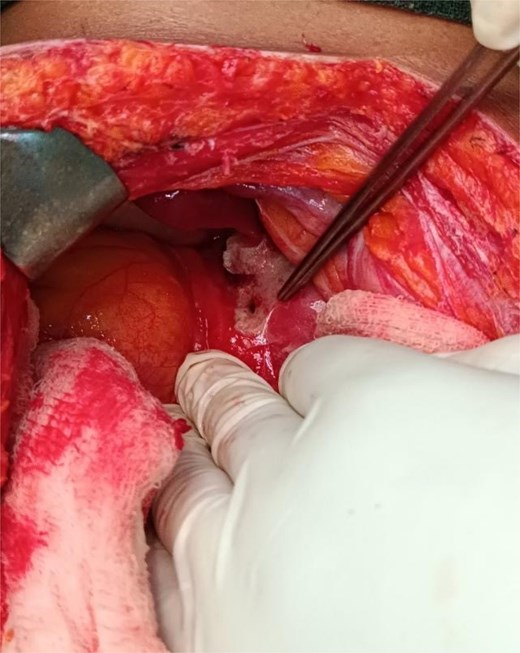

A Gridiron incision was made, and the abdomen was opened in layers. Intraoperatively, the appendix appeared grossly normal; however, 60 ml of turbid, greenish-yellow, foul-smelling fluid was noted in the surrounding peritoneal cavity. In view of the unexpected intra-abdominal findings and suspicion of an alternative pathology, the incision was extended to a Rutherford-Morrison curvilinear configuration for better exposure (Fig. 1).

On further exploration, a perforated pre-pyloric gastric ulcer was identified, which was ~5 × 3 mm (Fig. 2). The perforation was managed using a modified Graham’s patch repair. Thorough peritoneal lavage was performed. An appendectomy was also completed in the same setting. The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient recovered well and was discharged on the 7th postoperative day in stable condition.

Discussion

Abdominal pain is a ubiquitous presentation, most often benign, yet occasionally signifying life-threatening disease. The foremost priority in evaluation is the timely recognition of conditions requiring urgent intervention. Gastrointestinal perforation, although suggested by clinical findings, is definitively established through imaging. Characteristic radiologic features include free intraperitoneal or mediastinal air, or sequelae such as abscess formation and gastrointestinal fistulae [4].

The primary objective of the surgeon is to exclude an acute surgical abdomen requiring immediate intervention. Acute appendicitis remains the most frequent etiology of right iliac fossa pain, typically presenting with fever, anorexia, nausea, or vomiting. Differential diagnoses include ureteric colic, diverticulitis, ruptured diverticulum, appendiceal mucocele, perforated cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and colitis. In women, gynecologic pathologies such as ovarian torsion, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, infarcted uterine leiomyoma, and pelvic inflammatory disease may closely mimic acute appendicitis [5–9].

Valentino’s syndrome, though rare, remains an important differential diagnosis of acute right lower quadrant pain [10]. The eponym originates from the actor Rudolph Valentino, who was hospitalized at the New York Polyclinic Hospital in 1926 and underwent appendectomy but later succumbed to complications of a perforated ulcer. Patho-physiologically, leakage of gastric, or duodenal contents into the right paracolic gutter induces localized peritonitis, closely mimicking acute appendicitis [11–13]. Diagnostic imaging, particularly chest or abdominal radiographs, may demonstrate free intraperitoneal air beneath the right hemi-diaphragm or adjacent to the right kidney, supporting the diagnosis of duodenal perforation [7, 9, 12]. In the absence of CT imaging, exploratory laparoscopy is advised for evaluation of an acute surgical abdomen when appendicitis is suspected but not definitively established [14]. In our case, plain radiograph revealed no evidence of free intraperitoneal air. Patient presented with an acute abdomen and strong clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis; however, CT imaging could not be obtained as the scanner was unexpectedly unavailable, necessitating an exploratory laparotomy.

Management options for perforated peptic ulcer include both non-operative and operative approaches. The Taylor method represents a conservative strategy, employing intravenous fluids, nasogastric decompression, antibiotics with Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, and close clinical monitoring. When surgery is indicated and the perforation site is identified, techniques such as simple closure with interrupted sutures, with or without omentoplasty, omental plugging, or Graham’s omental patch may be employed. Minimally invasiveclosure during exploratory laparoscopy, followed by H. pylori eradication, represents the preferred contemporary approach [15–17]. Management in our case involved exploratory laparotomy with simple closure of the defect reinforced by an omental patch, complemented by H. pylori eradication therapy.

Our case emphasized the importance of considering Valentino’s syndrome as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with right iliac fossa pain mimicking acute appendicitis, particularly in the background of peptic ulcer disease. It highlights the role of exploratory surgery when imaging is unavailable and emphasizes prompt recognition and surgical management of peptic ulcer perforation to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Valentino’s syndrome should be considered in right iliac fossa pain mimicking appendicitis, especially in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease. Acute abdomen requires prompt, cautious evaluation, as lower abdominal pain may indicate life-threatening conditions or atypical presentations of pathology from distant sites.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

None declared.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Peer and provenance statement

The article was externally peer-reviewed.

Guarantor

Dr. Bishal Budha. Email: bishalbc265@gmail.com.

References

Wijegoonewardene SI, Stein J, Cooke D, et al.

Iloh A, Omorogbe SO, Odigie C.