-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thuy Tram Ngo, Anh Vu Pham, Tran Bao Song Nguyen, Minh Thao Nguyen, Burkitt’s lymphoma of the appendix presented with acute appendicitis and ascites, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf928, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf928

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstracts

Primary appendiceal lymphoma is a rare malignancy, often of the Burkitt subtype, and may present as acute appendicitis. We report a 6-year-old boy with abdominal pain, distension, fever, and a palpable right lower quadrant mass. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis and hyperkalemia. Abdominopelvic computed tomography revealed an enlarged appendix, moderate ascites, and peritoneal thickening, findings that could be mistaken for perforated appendicitis with an underlying neoplasm and tumor lysis syndrome. Emergency laparoscopic appendectomy with peritoneal drainage was performed. Histopathology confirmed appendiceal Burkitt’s lymphoma. This case illustrates the diagnostic challenge of this rare tumor and highlights the importance of imaging and clinical assessment in early recognition and timely surgical management.

Introduction

Appendiceal neoplasms are rare, most commonly carcinoid, adenoma, or lymphoma [1]. They often occur in the setting of acute appendicitis, which is typically the first sign of appendiceal cancer [2].

Primary lymphomas of the appendix are exceedingly rare tumors, accounting for 0.015% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas [3]. Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) in the appendix has rarely been reported worldwide, especially in Vietnam. The diagnosis is typically made by histopathological examination after appendectomy, and treatment decisions are based on the specific circumstances of each case [4]. This article raises an important issue: which clinical or radiological signs suggest a malignant lesion in acute appendicitis, and when should emergency appendectomy be indicated?

We report a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with appendiceal BL following appendectomy.

Case report

A 6-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with 24 hours of abdominal pain, distension, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He was septic (GCS 13, pallor, and fatigue). Abdominal examination revealed marked distension with a positive fluid wave test (ascites). Diffuse abdominal pain with maximum intensity in the right lower quadrant and a palpable mass in the right iliac fossa was noted. There were no signs of peritonitis.

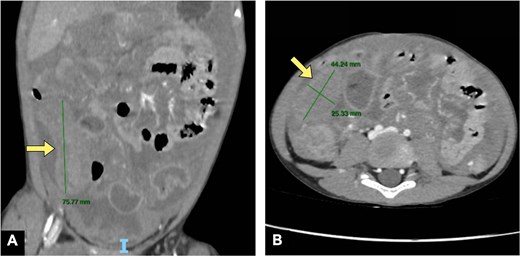

The complete blood count showed a WBC 32 × 109/L (neutrophils 88.91%), serum K+ 7.87 mmol/L, and a normal creatinine (71 μmol/L), suggesting that the hyperkalemia was not caused by acute kidney injury (AKI), which would be the typical cause in a septic patient. An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast showed a 7.5 × 4.5 × 2.5 cm solid mass in the right iliac fossa with large ascites (Fig. 1). Severe hyperkalemia, absence of AKI, along with marked leukocytosis and an abdominal solid mass, supported the initial suspicion of an aggressive malignancy. Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) laboratory tests showed hyperuricemia (of 542 μmol/L) and a normal level of phosphorus (1.28 mmol/L). We suspected perforated appendicitis with underlying malignant etiology leading to severe systemic sepsis and TLS.

Abdominal CT in the (A) coronal plane and (B) axial plane demonstrates a dilated appendix (yellow arrows) with a moderate amount of peritoneal fluid.

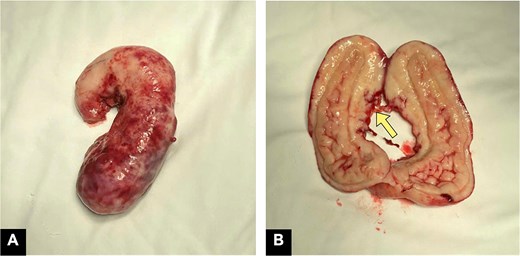

We performed an emergency laparoscopic appendectomy and abdominal drainage. Intraoperatively, there was a large amount of milky white ascites and an inflamed, enlarged appendix with a loss of serosal continuity and adhesions to adjacent structures (Fig. 2). Cytological and bacterial cultures of the peritoneal fluid revealed an acute inflammatory infiltrate without evidence of bacterial growth.

Surgical specimen. Macroscopic examination: (A) firm, sausage-shaped appendix with a thickened wall and edematous mucosa resulting in luminal narrowing; (B) discontinuity of the appendiceal serosa at the body (yellow arrow).

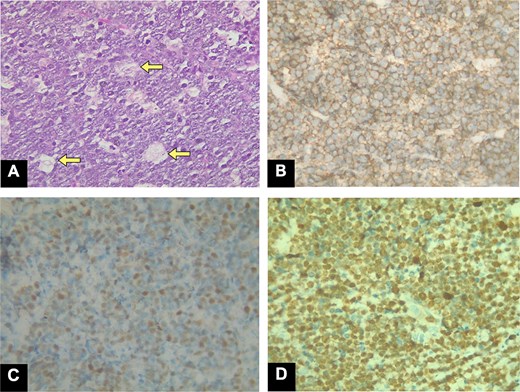

The appendiceal specimen was sausage-shaped, 12 × 3 × 2.5 cm, with a 1–1.5 cm wall thickness. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed sheets of medium-sized malignant lymphoid cells with round to oval nuclei, coarse chromatin, small peripheral nucleoli, and scant basophilic cytoplasm. The tumor cells were densely packed and interspersed with numerous pale macrophages containing nuclear debris, resulting in the characteristic ‘starry-sky’ appearance (Fig. 3A). Numerous mitotic figures at various stages were present. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that the tumor cells were positive for CD10, CD20, and BCL6, while negative for CD3, CD5, MUM1, Cyclin D1, CD23, CD15, and CD30 (Fig. 3B and C). Ki-67 was expressed in ~ 100% (Fig. 3C). These findings confirmed that this was appendiceal BL.

The H&E stain ×400 magnification. The tumor cells are densely arranged, interspersed with many pale macrophages containing nuclear debris, creating the typical ‘starry-sky’ pattern. (A) The background lymphocytes form the sky, while the macrophages represent the stars (arrows). (B) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) × 100: CD20 positivity, (C) BCL6 positivity, and (D) Ki67 expression (~100%).

The whole-body positron emission tomography/CT and bone marrow biopsy demonstrated Stage III according to the St. Jude/Murphy staging system. The patient then received the COPAD-M chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin, and methotrexate). After the first two treatment cycles, the interim evaluation showed a good response.

Discussion

Appendiceal BL typically presents as acute appendicitis. However, perforated appendicitis associated with ascites as the first manifestation of appendiceal BL is highly uncommon and diagnostically challenging. Histopathological examination of the appendectomy specimen is not routinely indicated in acute appendicitis unless it raises doubts macroscopically [4]. In this case, some specific signs suggested a neoplastic lesion.

First, the presence of an appendiceal mass on CT disproportionate to the size of a typical acute appendicitis should initially suggest a neoplastic appendiceal mass. Most cases of acute appendicitis are typically < 15 mm in diameter. Therefore, an appendix that exceeds this threshold should raise suspicion of a neoplastic cause, especially if the diameter is ≥ 25 mm [5]. Maintenance of the appendix’s vermiform morphology and lymphadenopathy and/or aneurysmal dilatation may increase the specificity for lymphoma [6].

Second, the peritoneal fluid characteristics in this case are atypical for generalized peritonitis due to perforated appendicitis. Perforated appendicitis typically produces small to moderate amounts of localized exudate or pus. Large amounts of ascitic fluid, especially if rapidly accumulating, are atypical and may suggest a neoplastic or lymphatic obstruction-related exudate [7, 8]. Furthermore, an important finding is an unusual appearance of the fluid, such as being bloody, which can indicate vascular invasion, or milky (chylous), which suggests lymphatic obstruction. Chylous fluid can be associated with conditions like lymphoma or mucinous tumors [9]. The lack of a foul odor or a strong fibrinous exudate in the peritoneal fluid suggests a possible underlying non-infectious process [10]. In this case, a key red flag was a large volume of rapidly accumulating milky-white ascites and the lack of a strong inflammatory picture in the presence of an enlarged appendix.

BL is highly sensitive to chemotherapy, primarily due to its extremely high proliferation rate. This makes chemotherapy the mainstay of treatment for BL [11]. In contrast, a surgical approach is not recommended as the initial treatment. Consequently, surgery is reserved for cases with emergent complications. In this case, due to the progressive deterioration caused by sepsis, an emergency appendectomy was indicated and performed as a source control measure in sepsis management [12].

Another emergency condition in this case is the suspected spontaneous TLS. This diagnosis is supported by the patient meeting the criteria for laboratory TLS under the Cairo–Bishop classification system. The patient met the Cairo–Bishop TLS criteria (hyperkalemia, hyperuricemia), suggesting primary TLS unrelated to previous chemotherapy [13]. TLS usually occurs after initiation of chemotherapy; however, it can occur spontaneously in the setting of a high proliferative rate tumor or a large tumor burden [13]. An emergency appendectomy was performed for sepsis control in this case [14].

Conclusion

Appendiceal BL is rare and can present as acute appendicitis. The decision to perform an emergency appendectomy was based on the true surgically emergent nature of the condition, with chemotherapy following as the primary long-term treatment.

Author contributions

Thuy Tram Ngo: Data collection, drafting, writing the article, and revision. Song Tran Bao Nguyen: Data collection and drafting. Vu Anh Pham: Data collection, drafting, and revision. Thao Minh Nguyen: Concept and design of the manuscript, data collection, drafting, writing the article, and revision. All authors participated in the approval of the final version.

Conflict of interest statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and/or publication.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was obtained as it’s a case report, but written consent was taken from the patient.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal upon request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Human and animal rights

The authors’ institutions do not require ethics committee approval or a case report or case series containing information on fewer than three patients.