-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

María Guadalupe Sánchez-Villegas, Jessica Jazmín Betancourt-Ferreyra, David Alberto Ortiz-Dumas, Luis Gerardo Frías-Méndez, María del Rocío Estrada-Hernández, Mario Eduardo Trejo-Ávila, Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the appendix and ileocecal region: a rare clinical entity, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf902, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf902

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), historically misclassified as inflammatory pseudotumor, is a rare, intermediate-grade neoplasm with low metastatic potential and a high recurrence rate. It primarily affects the lungs, with colorectal involvement being exceptionally uncommon. We present the case of a 32-year-old woman initially diagnosed with Stage III pelvic inflammatory disease, whose surgical exploration revealed an abscessed ileocecal mass. A right hemicolectomy was successfully performed, and histopathological examination confirmed an anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative IMT. The diagnosis is challenging due to the nonspecific nature of clinical and radiologic findings and significant histologic overlap with other spindle cell tumors. Immunohistochemistry and molecular profiling are essential for accurate classification, particularly in ALK-negative cases. Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment. This case highlights the importance of including IMT in the differential diagnosis of atypical intra-abdominal masses and supports the role of advanced molecular techniques in improving diagnostic accuracy and management.

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT), historically misclassified as inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT), is a rare, intermediate-grade neoplasm with low metastatic potential but a high recurrence rate. It features spindle cell proliferation of myofibroblasts with a minor fibroblastic component, arranged in a myxoid to collagenous stroma and accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate, predominantly lymphoplasmacytic [1, 2]. IMTs primarily affect children and young adults, most commonly arising in the lungs, followed by the abdominal cavity (mesentery, omentum, and peritoneum). Since Coffin et al. reported the first colorectal case in 1995, only 60 complete case reports had been published by 2019 [3–5].

Case presentation

A 32-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented with a 4-day history of worsening hypogastric and right iliac fossa pain, accompanied by nausea. A 39°C fever developed 2 days after symptom onset. Physical examination revealed lower abdominal tenderness, more pronounced on the right side, with guarding but no rigidity, no palpable mass, and normal bowel sounds.

Laboratory results showed an elevated leukocyte count 14.2 × 103/μl, with neutrophilic predominance 78.6%, hemoglobin 11.07 g/dl, hematocrit 33.42%, thrombocytosis 526 × 103/μl, elevated INR 1.44, prolonged prothrombin time 16 s, and activated partial thromboplastin time at the upper limit of normal 39.8 s. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated at 25.63 mg/dl. Renal function, electrolytes, and urinalysis were normal.

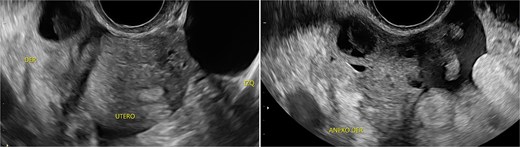

Stage III pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) was suspected based on ultrasound (Figs 1–3) and gynecological examination, which revealed mild bulging of the right lateral fornix, cervical motion tenderness, and a white, non-foul-smelling vaginal discharge. Empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated, followed by exploratory laparotomy via a Pfannenstiel incision. Intraoperative findings included an 8 × 5 cm uterus, edematous fallopian tubes, and a simple 5 × 5 cm left adnexal cyst. Cystectomy was performed.

Sagittal transvaginal ultrasound showing free fluid in the uterine fundus.

Transverse transvaginal ultrasound demonstrating a 4.7 cm bilocular cyst in the left ovary and a dominant follicle in the right ovary, with moderate periovarian fluid adjacent to the right ovary.

Transpelvic ultrasound reveals a heterogeneous mass adjacent to the right adnexa measuring 4.6 × 8.4 cm, predominantly hypoechoic with anechoic areas.

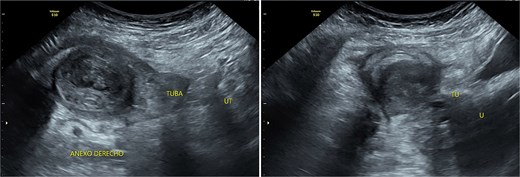

In the absence of urgent gynecological pathology, general surgery evaluated the patient for a colon mass. Midline laparotomy revealed a 6 × 8 cm abscessed cecal tumor, with purulent drainage and posterior wall adhesions. A right hemicolectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and mechanical side-to-side isoperistaltic ileotransverse anastomosis was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged after 1 week. Three-month follow-up showed no complications.

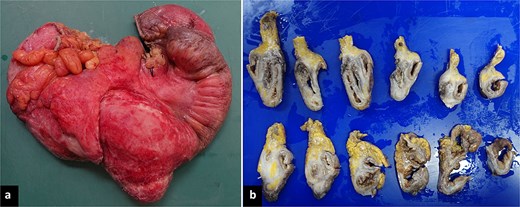

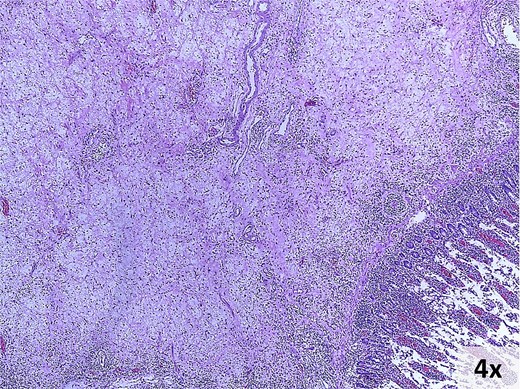

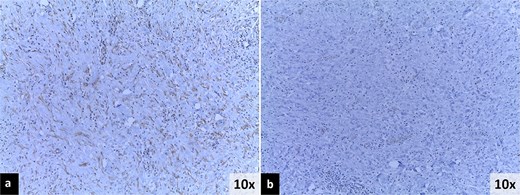

Pathology revealed a 9 × 8 × 3 cm ileocecal tumor with negative margins and uninvolved lymph nodes (Fig. 4). Microscopically, the tumor comprised fibroconnective stroma with hypercellularity of myofibroblastic spindle cells arranged in a storiform pattern, along with prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Fig. 5). Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for muscle-specific actin (MSA), vimentin, and focal desmin; Ki-67 index was 5%; calretinin, beta-catenin, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) were negative (Fig. 6). These findings confirmed an IMT diagnosis.

Macroscopic findings. (a) Right hemicolectomy specimen, 45 cm in length, showing an irregular brown-violet area with white plaques involving the cecum, appendix, and terminal ileum. (b) Formalin-fixed serial sections reveal a fibrous, whitish-brown lesion aggregating without infiltrating the described regions. The mucosa was preserved on cross-section.

Microscopic findings. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained photomicrograph of the lesion.

Immunohistochemistry findings. (a) Positive immunoreactivity for muscle-specific actin (MSA). (b) Negative immunoreactivity for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK).

Discussion

In colonic cases, the mean age at diagnosis is 31.8 years, with a bimodal distribution (0–18 and 30–50 years). The most frequently affected sites, in descending order, are the ascending colon, transverse colon, cecum, sigmoid colon, and descending colon [3].

The clinical findings include abdominal pain (56.7%), anemia—normochromic, hypochromic, or microcytic (28.3%)—a palpable mass (26.7%), fever (23.3%), weight loss (15%), symptoms of mass effect, and laboratory evidence of inflammation (thrombocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia, leukocytosis, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP). Anemia and obstruction are more common with right or transverse colon tumors [1, 3, 5].

The cervical motion tenderness—a minimum diagnostic criterion—along with fever and elevated CRP, led to a misdiagnosis of PID, with the ultrasound mass interpreted as a tubo-ovarian complex. Retrospectively, both low-normal hemoglobin and absence of mucopurulent cervical discharge were notable. When mucopurulent discharge and leukocytes on vaginal wet prep are absent, PID is unlikely, and alternative diagnoses should be considered [6].

IMTs lack distinctive imaging characteristics. Ultrasound often shows increased vascularity. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the imaging modality of choice for gastrointestinal IMTs, which typically present as hypodense, heterogeneous, well-defined masses frequently mistaken for colorectal carcinoma [7].

Grossly, IMTs present as well-circumscribed, multinodular masses with pushing margins and a white-gray, yellow, or tan coloration, measuring 1–20 cm (mean: 4–8 cm). Microscopically, the tumor cells exhibit vesicular nuclei, small nucleoli, and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. Three basic histological patterns may coexist within the same tumor: myxoid, hypercellular, and hypocellular [1, 8, 9].

IMT commonly expresses smooth muscle actin (80%–90%), MSA, desmin, calponin (60%–70%), ALK (50%–70%), focal cytokeratin (30%), diffuse vimentin, and wild-type p53. Reactivity for myoid markers is variable and decreases with increasing myxoid stroma. The Ki-67 index is usually low, consistent with the tumor’s intermediate-grade. β-Catenin, S-100, myogenin, and CD117 are negative. ROS1 and NTRK3 are the most common gene rearrangements in ALK-negative IMTs, each detected in 5%–10%. While immunohistochemistry defines phenotype, it lacks genotypic resolution, unlike fluorescence in situ hybridization; discrepancies may warrant additional molecular testing, such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1, 8, 9].

Differential diagnoses for predominantly hypercellular lesions, as in our case, include dedifferentiated liposarcoma, inflammatory leiomyosarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, dendritic cell neoplasms, spindle cell sarcomas, sarcomatoid carcinomas, and IPT—a heterogeneous reactive process that, unlike IMT, lacks genetic alterations and does not recur or metastasize [1, 2, 9].

Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment. Re-excision is advised for local recurrences. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends ALK inhibitors as first-line systemic therapy for advanced, recurrent, metastatic, or inoperable ALK-positive IMTs. Methotrexate plus vinorelbine/vinblastine and doxorubicin-based regimens have demonstrated high efficacy regardless of ALK status [8–10].

The Pathologic Soft Tissue Stage Classification (pTNM; AJCC 8th Edition) is recommended for staging. Adverse prognostic factors include myxoid stroma, ganglion-like or giant cells, necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, high mitotic rate, hypercellularity, and infiltrative margins [1, 8]. ALK-negative IMTs may exhibit higher metastatic potential to the lungs and brain [1, 2, 8, 9]. Colorectal IMT recurs in 14.3% of cases within 2–74 months, especially in older patients, tumors ≥8 cm, and following incomplete resections [1, 3, 5, 8].

Conclusions

Colorectal IMT is an exceptionally rare entity with nonspecific clinical and radiologic features, often mimicking other intra-abdominal pathologies. Diagnosis is challenging due to significant histologic overlap with other tumors, including IPT, now recognized as a distinct entity. NGS is increasingly important for ensuring diagnostic accuracy and guiding management. It is recommended as the standard diagnostic test in suspected cases with ALK-negative immunohistochemistry. However, it was omitted in this case owing to financial constraints. Surgery remains the primary treatment, and long-term follow-up is critical. Standardized terminology and improved molecular characterization are crucial for advancing understanding.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work funded by National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).