-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Abdelrahman S Elnour, Isam Taha, Mohamed Helali, Faisal Nugud, Preduodenal portal vein: two distinct case reports with unique presentations and tailored surgical management strategies, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 1, January 2025, rjae813, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae813

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is a rare congenital vascular malformation, which was first described by Knight in 1921 as an anomalous vein that lies in front of the duodenum, common bile duct, and hepatic artery instead of beneath them. This abnormal position may result in congenital duodenal obstruction and puts it in danger during operations around this region. PDPV is typically associated with other congenital anomalies, mainly intraabdominal and cardiac ones. The surgical management is usually determined intraoperatively based on evidence that the PDPV is the real cause of obstruction. We report two cases of PDPV each with a different presentation and management approach.

Introduction

The preduodenal portal vein (PDPV) is a rare congenital vascular malformation, characterized by an anteriorly placed primary portal vein trunk crossing anterior to the duodenum instead of the usual posterior course [1, 2]. PDPV is a rare cause of congenital duodenal obstruction (CDO) with few cases reported in the literature [2]. It is typically associated with other congenital anomalies, including malrotation, heterotaxia, polysplenia syndrome, situs inversus, cardiac defects, annular pancreas and atresia’s of the biliary tree, duodenum, and jejunum [1–4]. Preoperative diagnosis of this anomaly is infrequent. It is usually diagnosed in children who present with features of duodenal obstruction as a result of the PDPV itself or the coexisting anomalies and in some case as an incidental findings [4].

Here, we report two cases of PDPV each with a different presentation and management approach, highlighting the importance of individualizing surgical strategies.

Case 1

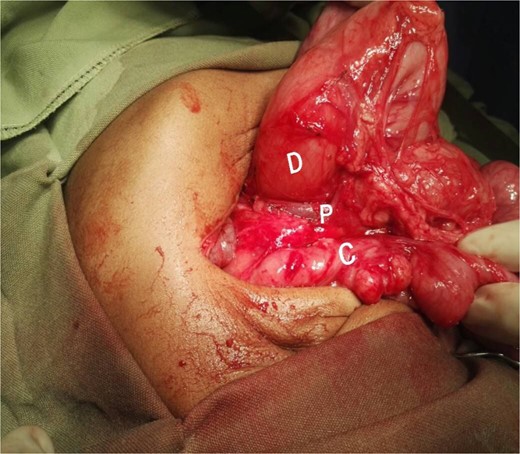

A 21-month-old girl presented with a history of bilious emesis since birth. The mother reported that the infant had several occasions of bilious emesis to a local doctor where she was managed as a case of dehydration. At 14 months of age, she was referred to a tertiary hospital for failure to thrive, where she was diagnosed with malrotation and underwent a Ladd’s procedure. However, the bilious vomiting continued. Upon arrival at our hospital, she was severely emaciated, dehydrated, and pale. Abdominal examination revealed visible epigastric peristalsis and right upper transverse surgical scar. After rehydration and correction of electrolyte imbalances, an upper gastrointestinal series showed signs of partial duodenal obstruction (Fig. 1). Abdominal exploration through the previous incision was done with findings of multiple adhesions that were gently released. The cecum was found in the left iliac fossa, and the appendix was not found. Potential causes of CDO such as malrotation, annular pancreas, and intestinal duplication were ruled out, following the duodenum, a PDPV was found causing the obstruction (Fig. 2). A diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy was performed, leaving the PDPV tunneled behind the anastomosis. The patient had a smooth post-operative recovery, gaining 1.7 kg in three weeks. Six months later, she was thriving, with her weight in the 90th percentile for her age.

Selected cut of an upper gastrointestinal contrast study showing dilated and elongated stomach, dilated first and second part of the duodenum, delayed passage of the contrast, and scanty gas in the distal abdomen keeping with features of chronic partial duodenal obstruction.

Intraoperative picture showing the PDPV crossing over the duodenum and causing duodenal obstruction. C, colon; D, duodenum; P, preduodenal portal vein.

Case 2

A 72-day-old female was referred to our hospital with yellowish discoloration of the sclera, noted in the first week of life, along with dark urine and pale stools. There was no history of vomiting or symptoms of bowel obstruction. On examination, she was a comfortable child with no apparent syndromic features. She was deeply jaundiced, but there were no signs of chronic liver disease. Her abdomen was soft, with a palpable smooth liver, the spleen was not palpable, and there was no ascites.

Her blood investigations revealed an elevated total serum bilirubin 8.7 mg/dl with the conjugated fraction comprising 66.3% of the total bilirubin level. Liver function tests showed elevated AST and GGT, with a markedly elevated ALP. Abdominal ultrasound revealed an enlarged liver and a shrunken, empty gallbladder. Based on these findings, biliary atresia was highly suspected.

After optimization, a cholangiogram was performed through a limited right subcostal incision. The hypoplastic and shrunken gallbladder was cannulated, confirming the diagnosis of type III biliary atresia. During the Kasai portoenterostomy procedure, a PDPV was incidentally noted (Fig. 3). Although the PDPV did not cause any obstruction, the patient had no preoperative vomiting, and no obstruction was observed after injecting 30 ml of air via the nasogastric tube. The portoenterostomy was successfully completed, and the patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery. She has been referred for follow-up with the pediatric gastroenterology team for care and monitoring.

Interpretive view of biliary atresia case showing a PDPV crossing the second part of the dedendum. D, dedendum; L, liver; P, preduodenal portal vein.

Discussion

The duodenum is one of the most common sites for congenital gastrointestinal tract obstructions. CDOs are most often categorized by their degree of obstruction (complete vs. partial), and their underlying etiology (intrinsic vs. extrinsic). Intrinsic causes are more prominent while extrinsic ones are less and include a wider variety of conditions including malrotation, PDPV, gastroduodenal duplications, annular pancreas, and cysts or pseudocysts of the pancreas and biliary tree [5]. PDPV was first described by Knight in 1921 as an anomalous portal vein that lies in front of the duodenum, common bile duct, and hepatic artery instead of beneath them, highlighting the unexpected position of this great vein, which makes it in danger during operations around this region [6]. CDO continues to present unique challenges; this is more evident in countries where resources are constrained. Healthcare providers may fail to recognize children with hidden anomalies resulting in the delay of diagnosis and malnutrition [2] as typically seen in case one.

Diagnosis of PDPV is usually at the time of abdominal exploration for duodenal obstruction [2, 7, 8], or other intraabdominal pathologies including biliary, and jejunal atresias, and as well hiatal hernia [1, 4, 9]. The surgical management strategies of the PDPV are determined intraoperatively based on evidence that the PDPV is the cause of obstruction. This can be identified by a significant change in the duodenal caliber proximal and distal to the site of crossing, or evidence of obstruction after nasogastric tube air injection, in those cases surgical bypass in a form of duodenoduodenostomy, or gastroduodenostomy is recommended [2, 4, 7]. However, incidental finding of PDPV without evidence of obstruction makes the surgical correction unnecessary [3, 9], as in case two. The presence of CDO with Ladd’s bands, along with the rarity of PDPV, may lead to failure in identifying this venous anomaly as a cause of obstruction during the initial operation [2], as in case one.

Conclusion

CDOs are fascinating anomalies characterized by a wide spectrum of etiologies, presentations, and associated anomalies. Pediatric surgeons should be aware of rare anomalies like PDPV as a potential cause of CDO; therefore, we recommend considering PDPV in any child with CDO. An incidental finding of PDPV without evidence of obstruction does not necessitate surgical correction.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.