-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Brian Cunningham, Daryl Blades, Gerarde McArdle, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in situs inversus totalis—surgical technique and procedure safety using anatomical checkpoints, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 7, July 2024, rjae450, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae450

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Situs inversus totalis (SIT) is a rare congenital condition in which there is complete transposition of both the thoracic and abdominal viscera. Given how infrequently this abnormality is encountered, operating on patients with SIT can be technically difficult and challenging for the surgeon. This case report outlines the steps used to successfully carry out a laparoscopic cholecystectomy on a patient with SIT. The aim of this report is to highlight the technical difficulties encountered during this common surgical procedure. By sharing our operative experience, we hope to assist operating surgeons in their perioperative planning when faced with a similar case. Our approach to port placement, dissection of Calot’s triangle, and achieving adequate tissue tension is discussed. Ultimately, we believe that advanced planning, anticipation of likely challenges, and knowledge of strategies to overcome these can only be beneficial to the safety of performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with SIT.

Introduction

Situs inversus totalis (SIT) is a condition in which there is complete transposition of both the thoracic and abdominal viscera. It is a congenital condition with an incidence of 1:10 000 to 1:20 000 [1]. Operating on patients with SIT can be technically difficult and challenging for the surgeon for many reasons. It means altering the traditional theatre set up, port placement and assuming the surgeon’s ambidexterity. Changes in orientation of anatomy have been shown to cause an increase in surgical complications [2]. A review article published by Kowalczyk and Majewski detailed significant errors that arise from aberrant anatomy [2], specifically in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) complications arising from aberrant hepatic vessels and bile duct positioning. LC techniques for SIT have been described in He et al. including variation in port placement [3].

This case report focuses on the set up and technique used by a right hand dominant surgeon to perform LC safely in a patient with SIT. Given that surgical complications can arise from changes in anatomy, particular attention was given in this case to perform anatomical checkpoints such as line of safety and critical view of safety [4, 5].

Case report

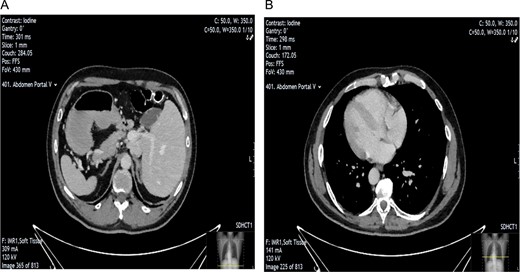

A 54-year-old man, known to have SIT, was referred to the general surgical unit with epigastric pain, dysphagia, and weight loss. Initial investigation with upper GI endoscopy was technically difficult and raised the suspicion of gastric volvulus. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was subsequently carried out (Fig. 1). This showed SIT and mild nodularity of the gallbladder wall, thought to represent a 7.1 mm gallbladder polyp. Given the patient’s symptoms, the decision was made to perform an LC [6].

CT scan showing evidence of SIT. Image A shows position of gallbladder and evidence of nodularity. Image B showing dextrocardia indicative of SIT.

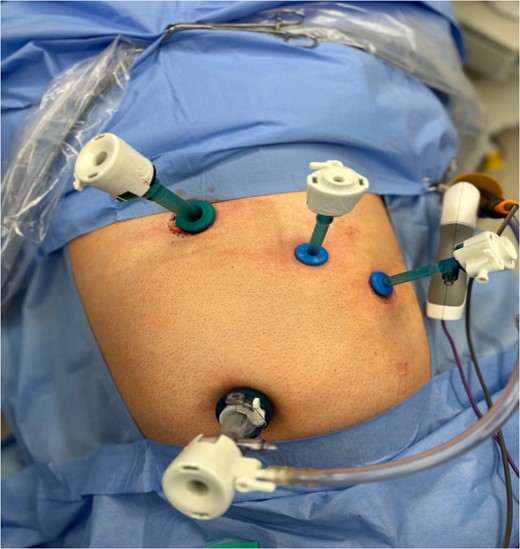

The patient was put under general anaesthesia and placed in the supine position. The operating surgeon and first assistant operating the camera stood on the patient’s right-hand side. The second assistant and scrub nurse stood opposite on the patient’s left. The laparoscopic stack and screen were positioned at the patient’s left shoulder. A 12 mm port was placed in the infra-umbilical position following open Hassan cut down, and pneumoperitoneum was achieved with CO2 at 14 mmHg and a flow rate of 5 LPM. One 11 mm port and two 5 mm ports were inserted under direct vision in an exact mirror image of a standard LC with normal anatomical positioning. This involved port placement as follows; 11 mm port in the subxiphoid area, 5 mm port in the left medial subcostal area, and a further 5 mm port in the left lateral subcostal area (Fig. 2). The patient was positioned with 30 degrees of head up and 20 degrees of left sided tilt. Upon insertion of the camera, it was imperative that we correctly orientated ourselves to the patient’s anatomy (Fig. 3).

Intra-operative image taken illustrating laparoscopic port setup.

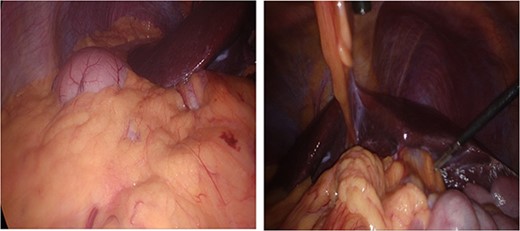

Anatomical variation with anatomical left lobe of the liver and fundus of the stomach in right upper quadrant (RUQ) and gallbladder in left upper quadrant (LUQ).

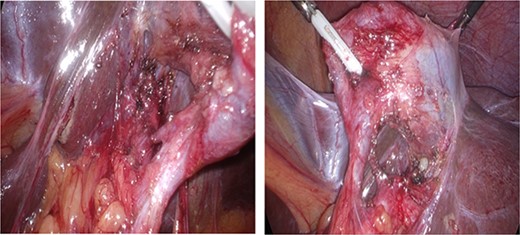

Dissection started with separation of omental adhesions from the fundus of the gallbladder. This was done using a combination of hook diathermy and blunt dissection techniques. Once these adhesions were taken down, Calot’s triangle was identified. Anatomical cross check was performed as usual by identifying segment IV of the liver, Hilar plate, and the hepatic pedicle. Dissection was kept lateral to the ‘line of safety’ and well above Rouviere’s sulcus. The operating surgeon used their right hand for the majority of dissection of Calot’s triangle as usual. Once Calot’s triangle was dissected, two structures were identified going into and out of the gallbladder, and Strasburg’s ‘critical view of safety’ (Fig. 4) was seen [4, 5]. The cystic duct and cystic artery were clipped with three 10 mm endoscopic haemostatic clips and ligated. The 10 mm ligaclipper was inserted through the subxiphoid port and placement of clips was controlled using the surgeon’s left hand. The gallbladder was then dissected from the gallbladder fossa and removed via the umbilical port in a Bert bag.

Critical view of safety with plane of dissection lateral to line of safety; two structures are viewed both entering the gallbladder and the lower border of the gallbladder dissected from the liver.

Discussion

In the case described by He et al., the main challenge faced by the right-hand-dominant operating surgeon was using their left hand for dissection, clipping the cystic artery and duct, and cutting these structures. Repeated examination and cross-checking of anatomy were key to ensuring safety during LC in SIT. A four-port approach was used, mirroring the exact setup of the standard LC (Fig. 2). During the dissection, the surgeon proceeded in the way they were comfortable, dissecting with the right hand and applying surgical tension with the left. This approach meant that the majority of the dissection was performed towards the midline, where our anatomical checkpoints were crucial. We ensured that our dissection was well above Rouvière’s sulcus.

According to Orozakunov et al, surgeons should be comfortable with the anatomy before dissection and recognize that in SIT, the anatomy is a mirror image [7]. As mentioned in this case, the surgeon performed anatomy checkpoints, which were key to safely performing this case. Before clipping the structures, we ensured that Strasburg’s ‘critical view of safety’ was visible from both the medial and lateral aspects of Calot’s triangle (Fig. 4).

LC is a common procedure, which carries complications that are disproportionate to the symptomatology of biliary disease. In patients with SIT, it is critical that anatomical checkpoints are used to perform the procedure safely. Set up of the patient as an exact mirror image allows the surgeon to operate with their right hand so that there is some familiarity in an unfamiliar anatomical situation.

By sharing our operative experience, we hope to assist operating surgeons in their perioperative planning when faced with a similar case of SIT. Advanced planning of port placement, anticipation of likely challenges, and knowledge of strategies to overcome these can only be beneficial to the safety of performing LC in a patient with SIT.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.