-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pareena Sharma, Jay Shah, Nancy Sokkary, A case of image-guided hematometrocolpos drainage requiring tissue plasminogen activator in a pediatric patient, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 2, February 2024, rjae006, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hematometrocolpos (HMC) is a rare disorder that occurs when an anatomical anomaly like imperforate hymen causes menstrual blood to be retained in the uterus and vagina. There is no standard of care established for HMC beyond urgent vaginoplasty which requires a demanding post-operative course that may not be suited for all pediatric patients. This is a case report of successful use of image-guided percutaneous drainage of HMC with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) followed by vaginoplasty in a 13-year-old female with lower vaginal atresia. Additionally, this case explores the role of menstrual suppression and the need for individualized guidelines. It emphasizes the potential of image-guided percutaneous drainage with TPA as a promising, less-invasive treatment option for pediatric HMC as well as the impact on follow-up surgery.

Introduction

Hematometrocolpos (HMC) occurs when menstrual blood is retained due to anatomical anomalies like imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, and vaginal atresia. Approximately 90% of cases are secondary to imperforate hymen [1]. HMC is a rare condition with a prevalence of 1 in 2000 females [2]. Patients with HMC present with amenorrhea and lower abdominal pain as well as a pelvic mass, constipation, and urinary retention [2, 3]. HMC can be missed without imaging [1].

There is no standard of care established for HMC. In cases of imperforate hymen, patients receive hymenectomy. And in cases of lower vaginal atresia, vaginoplasty can provide definitive treatment [4, 5]. Vaginoplasties require a demanding postoperative course for adolescents like the use of vaginal stent and dilation which may not be practical for patients who are not psychologically mature [6]. Management options for delaying surgery include menses suppression with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or continuous hormones [7]. However, these treatments are sparingly successful and can prolong pain [7]. Incision and drainage of HMC is avoided due to high risk of ascending infection [8].

Interventional radiology’s role in treating HMC has emerged as a less-invasive treatment option for patients who want to defer surgery. In this report, we describe the successful peri-operative management of a 13-year-old female with HMC with use of image-guided percutaneous drainage with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA).

Case report

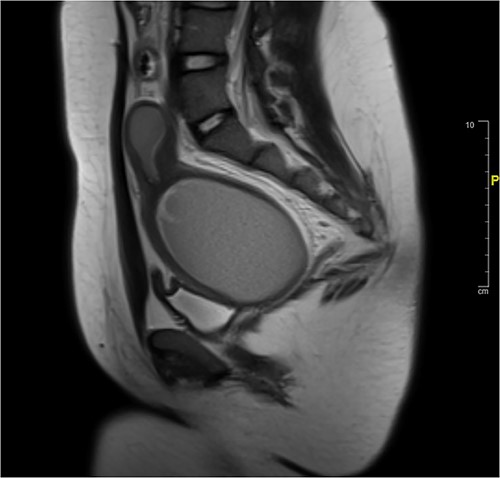

A 13-year-old female presented to the emergency department for increasingly severe chronic cyclic abdominal. She reported thelarche and pubarche at age 11 but had not reached menarche. Physical exam was significant for general abdominal tenderness and firm abdominal mass. External genitalia were notable for a normal hymen but no vaginal opening or bulge. On rectal exam, a firm mass was palpated ~4 cm proximal to anal opening. Imaging confirmed HMC with distension of the proximal vagina measuring 9.9 cm in its greatest dimension. The area of vaginal agenesis was ~5 cm from distal end of HMC to the perineum (Fig. 1).

Menses was suppressed with norethindrone acetate and surgical correction was planned for 10 months later. Due to ongoing pain, image-guided percutaneous drainage was performed to enable participation in school activities until surgery.

Attempt was made to perform US-guided drainage in IR using largest bore drain (12F) but the HMC had organized into a large clot and was too thick for drainage. Four mg of TPA was then injected into the HMC to allow breakdown of the clot, after which 300 ml of blood was successfully drained (Fig. 2).

Pre-vaginoplasty MRI- Image was taken after IR drainage and suppression to allow distension pre-vaginoplasty.

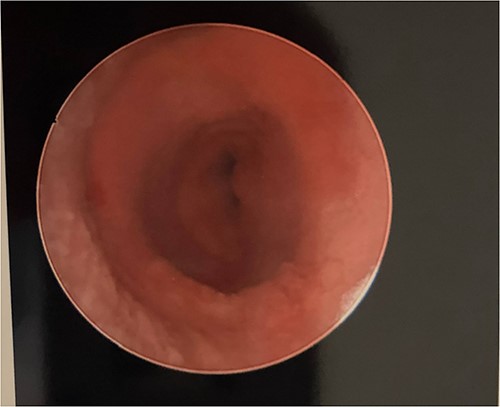

She remained suppressed and without pain. She discontinued the norethindrone acetate 2 months prior to surgery to allow re-accumulation of the HMC. The surgical team was prepared to perform a buccal graft vaginoplasty, but sufficient mobilization of the native vaginal tissue allowed for an uncomplicated vaginoplasty without graft. A uterine tamponade balloon was placed and expanded with 180 ml of sterile water. Postoperatively she was admitted with a uterine tamponade balloon and urinary catheter in place. These were removed on postoperative Day 5, and she was discharged home on doxycycline and metronidazole for a 7-14 day course and 25 mm stent at night for 14 days. Subsequent vaginoscopy revealed a normal upper vagina and well-healing suture line, able to accommodate a 25 mm rectal dilator (Fig. 3). At the time of writing, she is 5 months postoperative and using the stent a few times a month.

Discussion

This rare case highlights the challenges and considerations in the management of HMC, demonstrating the utility of image-guided percutaneous drainage with TPA, in addition to a more specific postoperative course than previously published studies [1]. The patient was relieved of chronic abdominal pain and was able to optimally plan surgery. The ability to minimally invasively treat HMC acutely in this case prevented the patient from possible complications like hydronephrosis and uterine perforation that can result delayed treatment [9]. Percutaneous HMC drainage is considered when HMC measures ≥3 cm and when there is a good anatomical opportunity for percutaneous approach [8]. For cases with difficult percutaneous approach, surgical laparoscopic drainage can be considered. Childress et al. reviewed eight pubertal patients with several obstructive Mullerian anomalies including distal vaginal agenesis, obstructed uterine horn, and high obstructed hemi-vagina [8]. Childress et al. [8] demonstrated successful postponing of surgery using ultrasound-guided drainage of the HMC in patients with >3 cm distal vaginal agenesis, one of which had exceptionally complex periprocedural planning with obstructed uterine horns.

Notable in this case was the decision to suppress the patient’s menses with norethindrone acetate for ten months before pursuing surgical correction. The use of menses suppression therapy in managing HMC prevents the re-accumulation of menstrual blood and relieves HMC symptoms. Following the percutaneous drainage, norethindrone acetate allowed the patient to remain pain-free and delay surgery as needed. Another medical option for menses suppression includes GnRH analogues which have the best rate of amenorrhea. However, prolonged use of GnRH analogues is associated with decreased bone mineral density and menopausal symptoms [8]. The optimal duration of menstrual suppression therapy remains uncertain and should be individualized with each patient.

HMC drainage and vaginoplasty are procedures that carry a risk of infection, and antibiotic prophylaxis is a common practice to reduce this risk. In this case, the patient was started on a 7 to 14-day course of doxycycline and metronidazole antibiotics given the amount of purulent discharge typically noted when postoperative stent is removed. This is reported by expert opinion but and has not been formally studied. Future research should focus on determining the optimal duration and choice of antibiotics in this specific clinical scenario. This case used a novel stent immediately postoperatively, a uterine tamponade balloon. Although used by experts, it has not been well described in the literature. The uterine tamponade balloon allows for easy placement and removal in its deflated state and then expansion with fluid to create light pressure of a stent.

In conclusion, this case report highlights the potential of image-guided percutaneous drainage with TPA as a less-invasive treatment option for pediatric HMC. It emphasizes the need for further research, standardization, and collaboration between specialists, underlining the importance of its broader clinical adoption.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.