-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mauricio E Perez Pachon, Rachel Horton, Kristen K Rumer, Appendiceal ganglioneuroma incidentally found during resection of recurrent rectal cancer: case report and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 2, February 2024, rjae019, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae019

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ganglioneuromas (GN) are benign neuroblastic tumors that arise from neural crest cells. Since they present with nonspecific symptoms, diagnosis is often incidental. We are reporting a case of an adult appendiceal GN incidentally found during rectal cancer surgery. A 42-year-old male was diagnosed with recurrent rectal cancer after experiencing urinary difficulties and buttock pain. A multiple-stage pelvic exenteration was carried out after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation. Prophylactic appendectomy was done during the course of surgery, and pathology reported an appendix with GN at the distal tip. GN are often found incidentally and rarely cause appendicitis. Depending on their location and size, they might become symptomatic. While there is some controversy on whether surgery is the treatment of choice for all GN, diagnosis is rarely apparent preoperatively, and all appendiceal masses should be resected.

Introduction

Ganglioneuromas (GN) are benign, slow growing neoplasms within the spectrum of neuroblastic tumors. These tumors arise from neural crest cells (develop from sympathetic nervous ganglia, including the adrenal medulla). They are the most mature entity of neuroblastic (NB) tumors [1–3] with a very low potential for malignant transformation or metastasis [4, 5]. Histologically benign, GN are composed of mature or immature ganglion cells, neurites, accompanied by Schwann cells and fibrous tissues. In contrast, other immature elements, such as neuroblasts, intermediate cells, and mitotic figures are not part of GN [6]. GN were first described in 1870 by Loretz [4] and are extremely rare with an incidence of 1:100 0000. GN more commonly affect young females (3:2 female: male ratio) with 60% of reported diagnoses before the age of 20 years [2]. Clinical presentation of GN is nonspecific, and thus, diagnosis is often made incidentally (26%–78%) [3]. They can be located throughout the body but have been most commonly described in adrenal glands. Depending upon location, GN can present with symptoms due to bleeding or compression onto adjacent structures. In the gastrointestinal tract, GN can present with abdominal pain, bowel obstruction, perforation, colitis, appendicitis, anemia, melena, or hematemesis [7].

Diagnosis of GN before resection is often not possible. Clear distinction of GN from other neoplasms based on imaging is currently not possible. Catecholamine metabolism was reported in up to 39% and 57% of GN, determined by increased blood or urine levels of homovanillic acid and/or vanillylmandelic acid, or tumor uptake of the norepinephrine analogue metaiodobenzylguanidine [6]. Current reports on GN shows variation in basic characteristics like mean age of onset, most frequent location, or post-surgical complication rates. Decarolis et al. showed excellent outcomes for pediatric GN after resection, in a cohort of patients registered at the German neuroblastoma trials between January 2000 and December 2009. This cohort included patients under 21 years of age with 144 maturing and 18 mature GN [8] in three main locations: adrenal, thoraco-cervical, and thoraco-abdominal [3]. Most data are from juvenile patient registries, while series including adult patients are generally restricted to adrenal location. Fewer than 200 appendiceal GN have been found during autopsy series evaluating >70 000 appendixes. Moreover, <10 cases of appendiceal GN found incidentally during surgery have been reported. Adult GN have been reported as a rare cause of appendicitis. [1, 2, 9–12]. Here we report a case of adult appendiceal GN incidentally found during surgery for recurrent rectal cancer. We will discuss our findings based on current literature about GN surgical treatment and other authors’ experience approaching such rare entity.

Case presentation

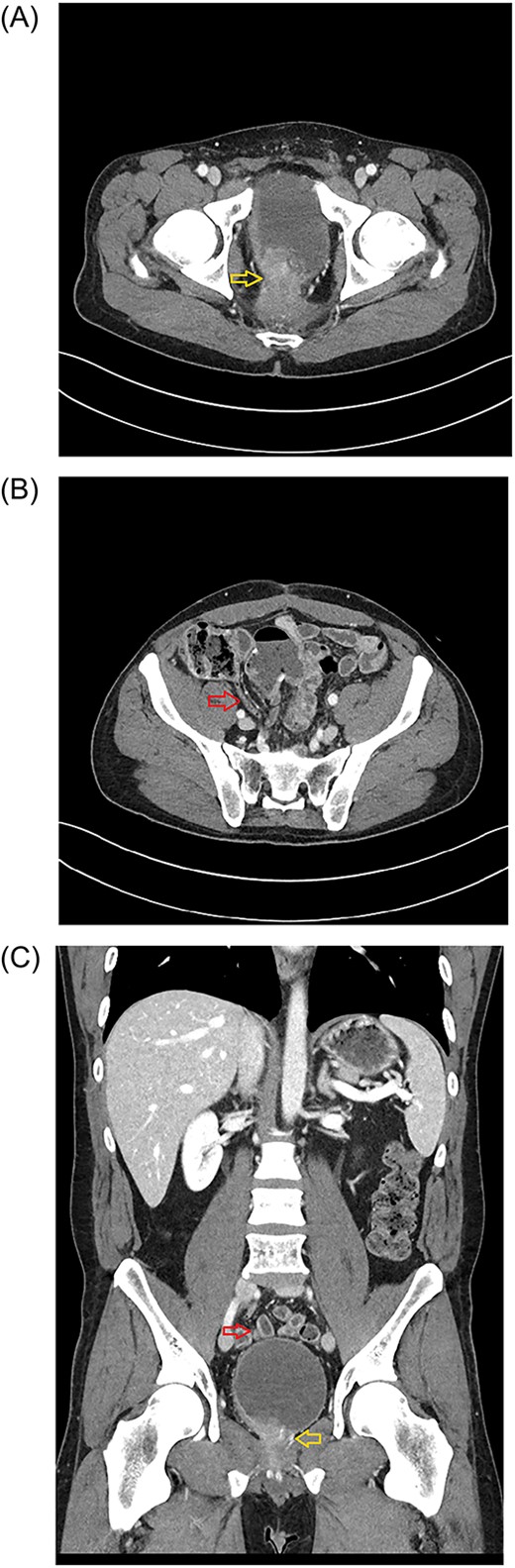

A 38-year-old otherwise healthy male was diagnosed with T3N1 microsatellite-stable rectal cancer after experiencing rectal bleeding, weight loss, and constipation. He completed a two-month course of neoadjuvant chemoradiation, followed by low anterior rectal resection, and three cycles of adjuvant Capecitabine. He declined additional adjuvant chemotherapy due to side effects. Recurrence was found at the colorectal anastomosis 7 months after his initial resection. He underwent abdominoperineal rectal resection with permanent end colostomy. Pathology was moderately differentiated pT2N1M0 microsatellite stable rectal adenocarcinoma. He completed an additional 3-month course of adjuvant chemotherapy before being lost from follow up for almost 2.5 years. He returned to care due to difficulty with urination, numbness, and stabbing pain over the right buttock. Now 4 years out from his initial diagnosis, imaging and biopsy confirmed pelvic recurrence. Imaging showed a presacral soft tissue mass invading prostate and abutting bladder and sacrum, suggestive of perineural spread of the tumor along the right S3 and S4 nerve (Fig. 1A). He completed four cycles of neoadjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) + Panitumumab, followed by neoadjuvant chemoradiation before planned two-stage surgical resection with intraoperative radiation (IORT).

Axial plane of the abdominopelvic CT scan (January 2023) showing the tumor invading bladder (yellow arrow) (A) and the pelvic location of the appendix (red arrow) (B). Abdominal CT scan (Coronal plane) (C) showing the tip of appendix (upper, red arrow) and tumor invading bladder (lower, yellow arrow).

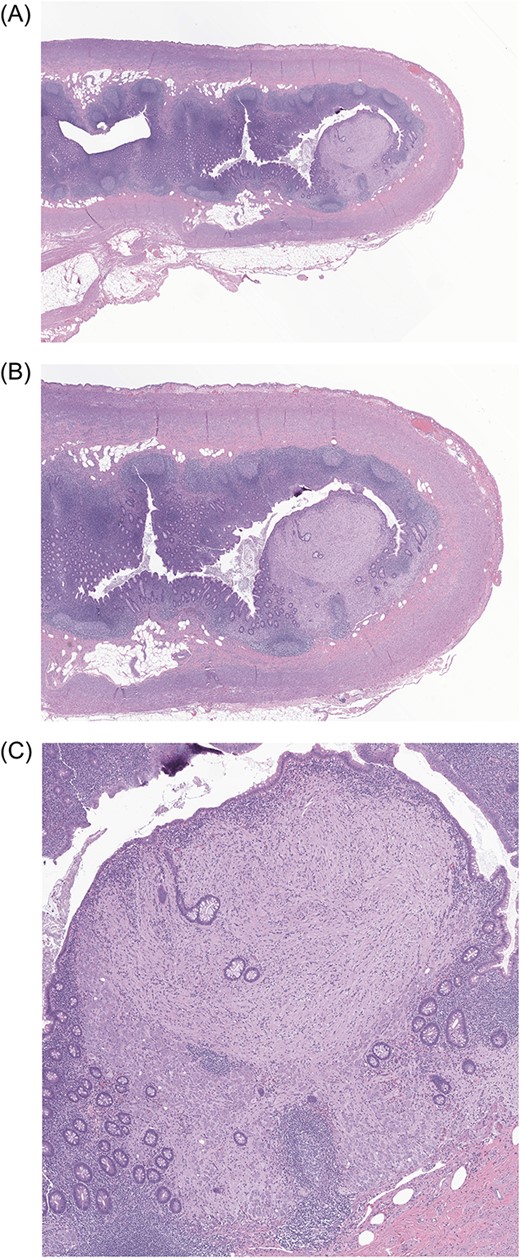

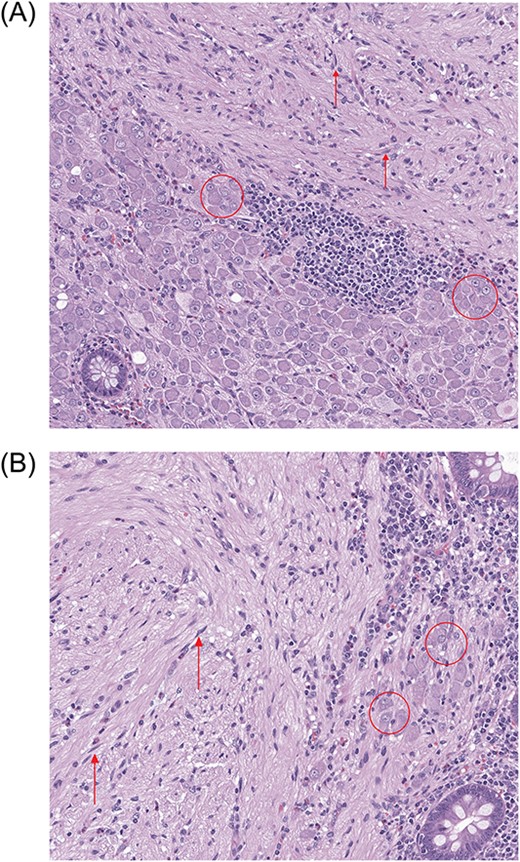

The first stage included a posterior subtotal sacrectomy plus neurectomy of pudendal nerves and neuroplasty of both sciatic nerves. An interval recovery of 24 hours was allowed. The second stage included complete exenteration including bladder and prostate, completion of subtotal sacrectomy, ventral rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap reconstructive surgery to fill the pelvic defect, creation of an ileal conduit and delivery of IORT. During the abdominal portion of the case, prophylactic appendectomy of a benign appearing appendix was done because his anatomy was such that the appendix naturally resided in the pelvis (Fig. 1B and C) and the operative surgeon wanted to avoid need for future appendectomy in a multiply reoperative and irradiated pelvic-exenteration field. His postoperative clinical course was difficult, which was expected for this type of surgery including need for transfusion, urinary tract infection, posterior wound dehiscence, pelvic abscess requiring drainage, and neuropathic leg pain accompanied by foot drop. He has had a slow but steady recovery from the extensive surgery. Unexpectedly, definitive pathology reported appendix with GN at the distal tip (Figs 2 and 3). Given the incidental nature of this finding, preoperative imaging was reviewed. CT scans showed normal appendix without apparent mass (Fig 1B and C).

Low-power (5×, 10× and 40×) photomicrographs (A, B, C, respectively) of the patient’s appendix showing a solitary polypoid lesion located within the lamina propria of the appendiceal tip. The polypoid lesion is expanding the colonic lamina propria while displacing and distorting the adjacent colonic crypts.

High-power (100×) photomicrographs (A, B) of the patient’s appendix. Stroma of the polypoid lesion is composed of spindle-shaped cells (arrows) with numerous ganglion cells (encircled) present predominantly at the periphery of the polypoid lesion.

Discussion

Although GN has been reported to arise in nearly every organ of the body, reports of cases in the GI tract are extremely uncommon in literature [9]. In 1947, Stout [13] reported 10 cases of his own and reviewed 243 cases of worldwide-reported GN. He found that GN originated anywhere in autonomic ganglia, from the base of skull to the pelvis. However, most were located within sympathetic ganglia of retroperitoneal/posterior mediastinal regions and, less frequently, in parasympathetic ganglia next to abdominal viscera. Of the 243 cases, six of them were in the appendix. Collins [14] reviewed 71 000 human appendixes and found that only 199 specimens had GN, none of which obstructed the lumen of the appendix. Dahl et al. [15] reviewed 11 earlier reports of GN of the GI tract and reported six of these tumors were in the appendix, three manifested as acute appendicitis, while the other three were diagnosed incidentally at autopsy or during laparotomy.

Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis has been described at the ileocecal region in association with neurofibromatosis type 1 [10]. There is also a case report of GN in association with PTEN mutations [1]. Our patient had rectal cancer with APC and p53 variants of unknown significance (APC E1154* c.3460G > T, APC Q1367* c.4099C > T, TP53 c.919 + 1G > T). He was referred for genetic testing and counseling given his young age at onset of rectal cancer but declined. Ultimately, we suspect a spontaneous GN in his case.

Diagnosis of GN cannot be ascertained before removal of the mass; that is there are no definitive diagnostic imaging or biochemical tests [16]. Biopsies can be safely performed in hormonally inactive GN; however, overlooking poorly differentiated cells or other tumors due to insufficient sampling may result in fatal consequences for the patient. Patients with hypersecretion symptoms (episodic headaches, hypertension, sweating, and tachycardia) warrant additional workup before surgery.

Appendectomy alone has been shown sufficient for incidental GN within the appendix (rather than hemicolectomy) [17]. However, two retrospective reviews have challenged the necessity of any operative intervention for GN [16, 17]. One series of 24 GN patients, reported four with residual disease but had no recurrence after an average of 84 months. Six patients had postoperative complications including bowel obstruction, urinary retention, scoliosis, and Horner’s syndrome. Another series of also 24 GN patients found that 30% of them had postop complications such as Horner’s syndrome and intestinal obstruction. There was neither evidence of tumor progression nor mortality after 34-month follow up. In our case, we performed a prophylactic removal of the appendix from a patient who underwent extensive abdominopelvic surgery due to recidivate rectal cancer. The patient did not show any symptoms from the appendix or GN, and the lesion was not visible on retrospective review of preoperative imaging. Given the typically slow growth of GN, if our patient were not required to undergo surgery otherwise, the GN may have remained as a silent, asymptomatic tumor for him. It may have ultimately grown to a radiographically apparent lesion noted on his cancer surveillance scans or may have caused appendicitis.

Conclusion

GN are rare neuroblastic tumors. Their presentation depends on location, biochemical activity, and size. They are a rare cause of either appendicitis or appendiceal mass. Appendiceal GN are generally found incidentally on imaging or during resection of the appendix for other reasons (e.g. prophylactic, appendicitis). While there is some controversy on whether surgery is the treatment of choice for all GN, the diagnosis is rarely apparent preoperatively, and all appendiceal masses should be resected to rule out other malignant processes. As with any prophylactic resection, pathologic evaluation is critical as pathologies warranting follow up may be found.

Author contributions

M.P.: conceptualization, data curation, writing–original draft. R.H.: data curation, writing–review and editing. K.R.: conceptualization, data curation, supervision, writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors did not have financial interest nor receive any financial support of the products or devices mentioned in this article. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.