-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Melaku Teshale Gemechu, Dagim Leykun Berhanu, A common femoral vein aneurysm diagnostic challenge: a case report and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 10, October 2024, rjae652, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae652

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Common femoral vein aneurysms are rare and they are often misdiagnosed as soft tissue masses or as hernias. In this case report, we review literature and describe a patient who presented with left inguinal mass associated with ipsilateral limb swelling. He was initially misdiagnosed as cystic adventitial disease of common femoral vein. Later, he underwent surgical exploration and found out to have common femoral vein aneurysm which was treated by aneurysmectomy and lateral venorrhaphy.

Introduction

Although common femoral vein (CFV) aneurysms are uncommon, understanding them is critical because they can mimic soft tissue masses or inguinal/femoral hernias, and misdiagnosis can result in severe morbidity [1]. Here, we discussed a case of left inguinal mass that was diagnosed to have a left common femoral vein aneurysm during surgical exploration.

Case report

A 38-year-old male presented with a left-sided inguinal lump that had been present for 7 months. The lump was associated with painful swelling of the ipsilateral limb, which began in the thigh and progressively involved the entire leg. He had no history of trauma or family history of similar conditions. For this complaint, he was admitted to the internal medicine department with a diagnosis of proximal left leg deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and was treated with heparin. He subsequently took Warfarin for 6 months, but the inguinal and leg swelling persisted.

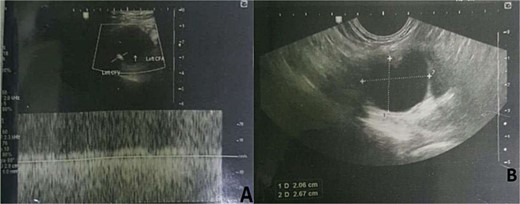

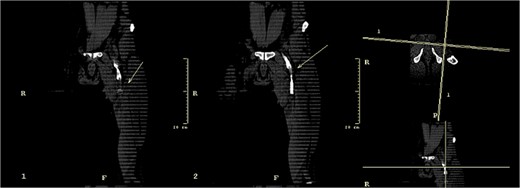

Up on surgical side evaluation, there was a 3 × 2 cm inguinal, slightly tender, firm mass with associated ipsilateral swollen leg. There was a leg-leg discrepancy of 5 cm and 2 cm at the calf and mid-thigh, respectively. His Doppler ultrasound showed left inguinal cystic mass (2.5 cm × 2.4 cm) in the femoral sheath compressing the CFV, but without communication. The blood flow in the compressed CFV was sluggish with no evidence of DVT (Fig. 1). CT venography also showed similar results (Fig. 2). He was then admitted to the surgical ward with the radiologist’s and operating surgeons’ impression of adventitial cystic disease (ACD) of the CFV, and he was scheduled for surgical excision of the presumed ACD.

Doppler ultrasound showing left inguinal cystic mass in the femoral sheath compressing the CFV, with no evidence of DVT.

CT Venography with a possible left common femoral vein adventitial cystic disease.

The intraoperative finding was a CFV saccular aneurysm with no extramural mass. A longitudinal venotomy was done over an aneurysmal part of the CFV, and the lumen was occluded with a thrombus and has a medial venous wall aneurysmal sac (Fig. 3). Thrombectomy and aneurysmectomy, along with the aneurysmal sac, were done. CFV lateral venorrhaphy was done after confirming that the remnant lumen had a comparable diameter to the proximal and distal parts of the vein. Due to the rarity of both ACD and CFV aneurysms, as well as the presence of thrombus in the aneurysmal sac, there was difficulty in making an exact preoperative diagnosis.

Intraoperative findings: (A) common femoral vein after longitudinal venotomy and thrombus was exposed; (B) the common femoral vein, pointed by forceps, after thrombus had been evacuated; (C) common femoral vein pointed by forceps after completion of venoraphy. CFA, Common Femoral Artery; CFV, Common Femoral Vein.

The patient had a significant decrease in leg swelling postoperatively. He completed his 3-month anticoagulant treatment course. On his last visit, 18 months after his surgery, there was no inguinal mass, and the leg swelling had subsided, with the last Doppler ultrasound showing patent CFV with normal flow.

Discussion

Aneurysms are abnormal dilations of blood vessels that most commonly occur in the arterial system. They are analogous to arterial aneurysms in that they tend to be localized and arise from a congenital weakness in the wall of the vessel [1].

Primary or congenital aneurysms are aberrant saccular dilatations that involve all the three layers of venous wall. They develop at any age and are evenly distributed across genders [2, 3]. They are caused by venous wall weakening as a result of inherited conditions [3]. In comparison, it is difficult to determine the cause in secondary or acquired venous aneurysms. However, it is important to assess for trauma, inflammation, degenerative changes, and venous hypertension [4]. Some case reports also suggest a link between pregnancy and venous aneurysm formation, although no causal factors have been identified [5]. Compression of iliac veins between the sacrum and iliac artery has also been reported as a potential cause [6].

Once clinically suspected, the diagnosis of venous aneurysm can be confirmed using a variety of methods, including duplex ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, venography is regarded as the gold standard diagnostic tool [1, 3, 7, 8]. Nearly half of the cases described in the literature did not receive an accurate diagnosis before operation [3].

A femoral vein aneurysm in particular can mimic conditions like inguinal or femoral hernias [1, 2]. Many are mistakenly identified as soft tissue masses of the lower extremities. These aneurysms might also appear as compressible painless or painful bulges in the inguinal region. The Valsalva or the dependent position might also increase the size of the bulge, creating a diagnostic challenge [1, 3]. Moreover, complications, including venous thrombosis, embolism, rupture, localized pain, and local mass effects with or without edema, can be the initial presenting symptoms [1, 2, 6–8].

Management of is determined based on location and size. Many small, asymptomatic, superficial venous aneurysms can be managed conservatively [3, 7, 9]. However, asymptomatic venous aneurysms may warrant surgical management due to the unpredictable risk of thrombosis and PE [1, 2, 7, 9]. Lower extremity venous aneurysms have a recurrent pulmonary embolism risk of 75%–80% despite anticoagulant therapy [1, 7, 9].

The indications for surgery include aneurysms that contain thrombus, symptomatic, ruptured, or had previous PE. The various surgical options include: ligation; resection with end-to-end anastomosis; resection with interposition graft; repair with tangential aneurysmectomy and lateral venorrhaphy; and aneurysmorrhaphy [3, 9]. The highest long-term patency rates for venous repairs were achieved using tangential excision and lateral venorrhaphy [2].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.