-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Alexandra Z Agathis, Keval Ray, Bharti Sharma, Jennifer Whittington, Interval robotic cholecystoduodenal fistula repair and cholecystectomy for gallstone ileus: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2024, Issue 10, October 2024, rjae628, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjae628

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gallstone ileus is an uncommon pathology that often requires surgery in the acute setting to address the bowel obstruction, followed by definitive biliary management. Sparse literature cites the use of robotic technique in this setting. We present the case of an 86-year-old female with an independent functional status and a history of medically-managed cholecystitis, who previously declined cholecystectomy. Years later, she presented acutely with a small bowel obstruction secondary to gallstone ileus. At that time, she underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy, small laparotomy, and enterotomy for extraction of her gallstone. She returned 7 months later for an interval elective robotic-assisted cholecystectomy and repair of a cholecystoduodenal fistula. The duodenotomy was repaired in two layers with absorbable suture. Postoperatively, an upper gastrointestinal study showed normal passage of contrast without leakage. She recovered well, and shortly after returned to her baseline functional status.

Introduction

Gallstone ileus is a condition in which a gallstone travels via a biliary-enteric fistula and causes a mechanical small bowel obstruction. It is an uncommon pathology that often requires surgery in the acute setting to address the bowel obstruction. This enterolithotomy procedure can be performed via open or minimally invasive techniques, and with or without definitive biliary management—cholecystectomy and fistula repair. While the use of robotic-assisted cholecystectomy has increased > 30-fold across the United States over the last decade, there is sparse literature describing robotic surgery use in this setting [1, 2].

We present the case of an 86-year-old female who underwent a laparoscopic hand-assisted enterolithotomy, followed by an interval robotic-assisted cholecystectomy and primary repair of a cholecystoduodenal fistula.

Case report

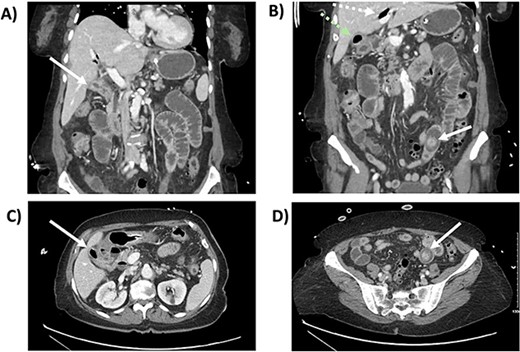

This is the case of an 86-year-old female with an independent baseline functional status and a history of hypertension and prior episodes of medically treated cholecystitis per patient preference. She presented to the Emergency Department at a public major tertiary care hospital for abdominal pain and was found to have a gallstone ileus. A CT scan showed: a gallstone in the jejunum causing a bowel obstruction proximally, pneumobilia, gallbladder wall edema, and pericholecystic fluid (Fig. 1). A nasogastric tube was placed for bowel decompression prior to proceeding for urgent operative exploration.

CT scan from the initial episode of gallstone ileus. A) Coronal CT: cholecystoduodenal fistula, B) Coronal CT: pneumobilia (superior, white dotted arrow) and air-filled gallbladder (inferior, green dotted arrow), impacted gallstone (solid white arrow), C) Axial CT: cholecystoduodenal fistula, D) Axial CT: impacted gallstone.

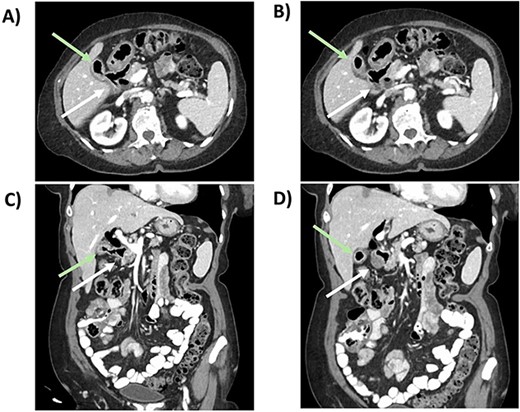

She underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy revealing a transition point secondary to the impacting 3-cm gallstone in the mid-jejunum. A small laparotomy was used to perform an enterotomy, stone extraction, and enterotomy closure. She had an unremarkable postoperative course. After 2 months, a follow-up CT revealed pneumobilia and a likely cholecystoduodenal fistula (Fig. 2). After medical optimization, she was scheduled for an elective robotic cholecystectomy and repair of the fistula 7 months later.

CT scan from follow-up after the index procedure. A) Axial CT: cholecystoduodenal fistula; air-filled gallbladder (superior, green arrow), duodenum (inferior, white arrow), B) Axial CT: air-filled gallbladder (superior, green arrow), duodenum (inferior, white arrow), C) Coronal CT: cholecystoduodenal fistula; air-filled gallbladder (superior,green arrow), duodenum (inferior, white arrow), D) Coronal CT: air-filled gallbladder (superior, green arrow), duodenum (inferior, white arrow).

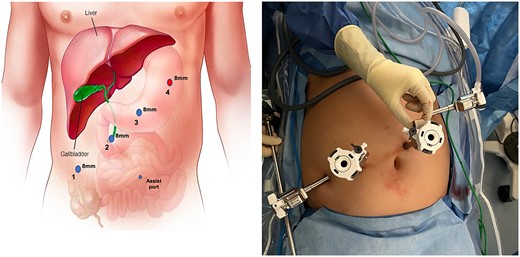

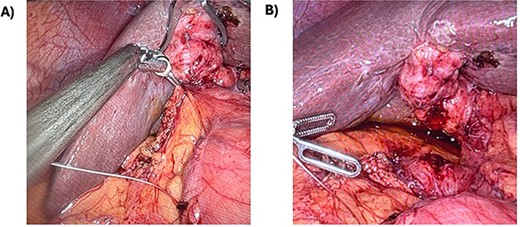

After anesthesia induction, indocyanine green 2.5 mg was administered. A Veress needle was used for entry, and four 8-mm trocars were inserted in her left mid-abdomen, two centrally and one in the right mid-abdomen (Fig. 3). An adherent small bowel loop was sharply dissected off the anterior abdominal wall. A small serosal injury was oversewn robotically with an interrupted 2-0 Vicryl suture after docking the DaVinci robot. The gallbladder was carefully separated from the adherent duodenum, and an approximately 1-cm fistula was noted (Fig. 4). The duodenotomy was repaired in two layers with an inner full thickness and an outer interrupted submucosal layer using absorbable suture (Fig. 5). Next, using FireFly to confirm biliary anatomy, the chronically inflamed gallbladder was dissected off the adherent common bile duct and right hepatic duct. After the critical view of safety was achieved, the cystic artery and duct were robotically clipped and transected. The intrahepatic gallbladder was dissected off the cystic plate, and a 10-French drain was left in the gallbladder fossa.

Trocar placement. Veress entry was performed at Palmer's point. Three additional 8-mm ports were placed approximately 6-cm equidistant as shown. The Veress entry site is increased in size to accommodate the #4 8-mm trocar. Instrumentation is as follows: 1) fenestrated bipolar 2) robotic camera 3) interchangeable port (monopolar scissor, robotic suction, prograsp) 4) tip-up with 4x4 inserted to elevate the liver 5) 5 mm assist port if needed.

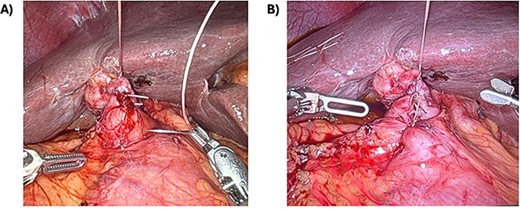

Cholecystoduodenal fistula. A) This is the cholecystoduodenal fistula prior to division. B) After division, there was a 1-cm duodenotomy.

Primary repair of duodenotomy. A) Using a stay suture, additional interrupted sutures were performed. B) Here is a view of the completed sutured repair with the stay suture still in-place.

She tolerated the procedure well, and was started on sips with oral medications on postoperative day 1. On postoperative day 4, an upper gastrointestinal study showed normal passage of contrast from the stomach, through the duodenum, and beyond without leakage of contrast (Fig. 6). Her drain was removed and she was discharged home on a regular diet on postoperative day 7.

Postoperative upper gastrointestinal study. The postoperative upper gastrointestinal study showed flow through the duodenum without contrast leakage.

At her postoperative week 3 visit, she continued to tolerate her regular diet and had returned to her baseline activity level. The pathology showed acute on chronic cholecystitis, without stones or evidence of malignancy.

Discussion

Gallstone ileus is an uncommon pathology, predominantly affecting older patients. It is an often morbid condition, with a 30-day mortality rate of approximately 6%–7% [3, 4]. Of 3.4 million mechanical bowel obstruction cases recorded in the National Inpatient Sample from 2004 to 2009, only 0.095% was from gallstone ileus [3].

The first stage of management is addressing the acute bowel obstruction. This may be performed via enterolithotomy alone, however it may also require a bowel resection if there is any perforation or significant ischemia. Depending on patient risk, definitive biliary management—which often includes cholecystectomy with or without fistula repair—may be pursued in the acute setting (one-stage), electively later (two-stage), or not at all. In low-risk operative candidates, cholecystectomy and fistula repair can be performed concurrently with enterolithotomy. However, research to-date shows that performing enterotomy with stone extraction alone results in better outcomes than when performed alongside more invasive procedures [5]. Thus, in higher-risk patients, many pursue expectant management and monitoring for clinical resolution before planning interval biliary management [3]. For patients undergoing this two-staged approach, the second surgery is typically performed after 4-6 weeks [6].

To date, very few similar cases have been cited. One report from 2023 discussed the case of a 70-year-old female, who was status-post an incomplete cholecystectomy years prior, who developed a cholecystoduodenal fistula secondary to a retained gallstone within the remnant gallbladder [7]. Ten days later, she underwent a robotic-assisted completion cholecystectomy and repair of the fistula with interrupted 3-0 permanent suture and an omental buttress. Another case report from 2023 described a 74-year-old-male who had gallstone ileus managed in the acute setting with a robotic-assisted enterotomy alone [8]. The authors used three ports to isolate the obstructed ileum, create a longitudinal enterotomy, extract the gallstone, and close the enterotomy in 2 layers. This was performed without cholecystectomy or repair of any mentioned fistula.

Conclusion

Gallstone ileus is a rare, morbid condition that presents two pathologies to manage: a mechanical bowel obstruction and cholecystoduodenal fistula, which requires upfront operative management of the obstruction, followed by possible definitive biliary management. Depending on the patient-specific risk factors, surgeons can opt for definitive biliary management in a one- or two-stage approach, or not at all. Many surgeons may choose a two-stage approach or to ultimately forego fistula repair in older, frail patients with comorbidities. To date, there has been sparse cited use of robotic technique in this context. Our case describes the successful management of gallstone ileus in a healthy, 86-year-old female via a two-staged technique with robotic cholecystectomy and cholecystoduodenal fistula repair, suggesting interval robotic repair is an effective and feasible option for definitive biliary treatment in patients including older, healthy candidates.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None declared.

Informed consent

The patient provided permission for case publication.