-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stephanie Chan, Gary Fermanis, Translocation of aberrant right subclavian artery to the ascending aorta—a treatment for dysphagia lusoria, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 2, February 2023, rjad054, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad054

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Generally, an aberrantly coursing right subclavian artery (ARSA), also known as ‘arteria lusoria’, is an incidental diagnosis of no clinical consequence. Where correction is indicated, popular practice is for decompression via staged percutaneous +/− vascular methods. Open/thoracic options for correction are not widely discussed. We report the case of a 41-year-old woman with dysphagia secondary to ARSA. Her vascular anatomy precluded staged percutaneous intervention. The ARSA was translocated to the ascending aorta via thoracotomy, utilizing cardiopulmonary bypass. Our technique is a safe option for low-risk patients with symptomatic ARSA. It obviates the need for staged surgery and removes the risk of carotid-to-subclavian bypass failure.

INTRODUCTION

The most common abnormality of the aortic arch vessels is an ARSA with an incidence of 0.3–3% in the general population [1]. When it occurs, the right subclavian artery (RSA) originates from the descending portion of the arch, distal to the left subclavian artery (LSA). The vessel then travels from the left side of the aortic arch to the right arm, crossing the midline of the body. In the most common variant, the ARSA passes behind the esophagus. Compression of the esophagus by the ARSA causes dysphagia. The entity ‘dysphagia lusoria’ was first described in 1787 by Bayford [2].

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 41-year-old female (161 cm, 106 kg, BMI 40.1 kg/m2) with a history of rheumatoid arthritis and hypertension had been experiencing retrosternal pain and progressive difficulty swallowing over ten months (without weight loss). She was referred by vascular surgery to cardiothoracic surgeons for surgical correction of an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA), which was perceived to be the cause of her dysphagia.

Investigations were performed to exclude other causes of dysphagia. These included gastroscopy, manometry and barium swallow. The results were equivocal. Barium swallow reported moderate luminal narrowing at the left posterior part of the esophagus, and moderate hold up of solids compared to liquids.

The most reported corrective strategy is a staged vascular procedure

Endovascular approach to occlude and cover the aberrant vessel at its origin.

If upper limb supply is subsequently compromised, carotid-to-subclavian bypass[3].

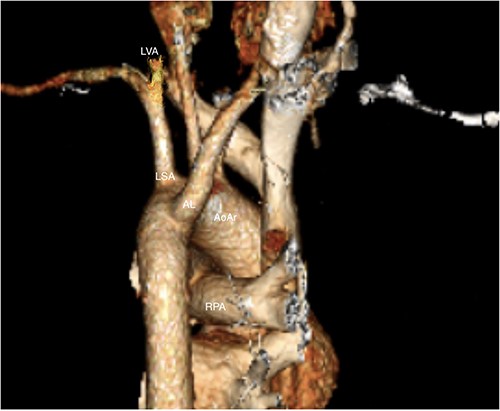

In this patient’s case, the above approach was not deemed possible. The origin of the aberrant subclavian artery was too close to the origin of the left subclavian artery to achieve a safe landing zone and graft seal without compromising supply to the latter. Of note, the patient had a very dominant left vertebral artery, supplying the majority of their postero-basilar circulation (Fig. 1).

LVA: Left vertebral artery, LSA: left subclavian artery, AL: arteria lusoria, RPA: right pulmonary artery, AoAr: aortic arch.

Open thoracic options were discussed. Surgeons emphasized the magnitude of surgical re-implantation and the risks associated with cardiopulmonary bypass. The patient insisted that symptoms were affecting her life so severely that she was determined to seek symptomatic improvement. She was of young age and good performance status.

Operative technique

Double lumen intubation was performed, and the patient positioned in modified left lateral decubitus position. The right lung was deflated, and an anterolateral thoracotomy was performed at the third intercostal space.

The ARSA was easily identified descending over the first rib; it was thinner and more friable than expected. It was carefully mobilized along its course, passing behind the esophagus to its aortic insertion (distal and posterior to the other arch branches). The thoracic duct was identified crossing the subclavian artery towards the esophagus and was ligated with silk ties.

Cardiopulmonary pulmonary bypass was initiated, with arterial cannulation of the lateral aspect of the ascending aorta, and venous cannulation of the right atrial appendage. The patient was cooled to 32° and cardioplegia was not utilized.

Perfusion pressures were reduced, and a side-biting clamp was applied to the aorta. An 8-mm Vascutek graft was anastomosed to the right lateral aspect of the ascending aorta.

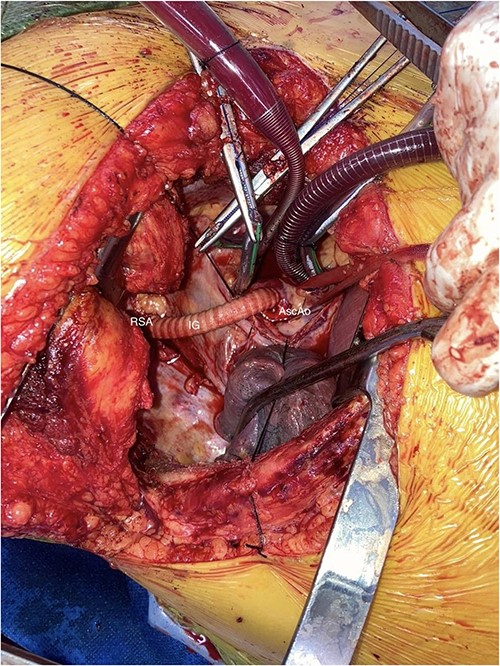

A Covidien vascular stapler was used to divide the aberrant vessel close to its aortic insertion. The vessel was then delivered back behind the esophagus into the right chest. The ARSA was anastomosed (end-to-end) with the Vascutek graft, which had already been anastomosed onto the ascending aorta (Fig. 2).

AscAo: ascending aorta, IG: interposition graft, RSA: right subclavian artery.

De-airing was performed, cardiopulmonary bypass was weaned and lines were removed.

The thoracotomy was closed routinely, with single chest drain left in situ. The patient was returned to ICU ventilated. She was discharged from ICU on post-operative day two. The patient reported immediate improvement in swallowing.

Given instrumentation of the thoracic duct, care was taken to reintroduce fats to the diet slowly. Operative drains were left in situ and frequently inspected for evidence of chyle leak. A fat challenge was performed before the chest drain was removed.

There have been no post-operative issues to the time of writing (12 months). Post-operative pain resolved over the course of two months. Dysphagia is reported to have completely resolved since surgery.

DISCUSSION

The presence of an ARSA is usually incidental and does not require intervention.

Available literature focuses on staged percutaneous re-direction of flow. Furthermore, returning supply to the right-subclavian artery is not always performed, which may compromise function of the right upper limb—particularly in a younger patient.

The considerable risks associated with cardiopulmonary bypass, and surgery to great vessels should be weighed against the patient’s symptoms. Patients need to be counselled about the material risks they face (including death, stroke and other surgical misadventure). In the absence of aneurysm of the ARSA, patients need to seriously consider whether their symptoms are severe enough to warrant open intervention. In this case, the patient underwent clinical counselling and was seen as an outpatient on several occasions before the decision to undertake surgery was made.

This case report presents an option for surgical correction. This approach has the benefit of

immediately restoring supply to the upper arm, negating the need for return to theatre,

removing the ARSA from behind the esophagus, immediately and completely relieves obstruction. By comparison, percutaneous techniques leave the ARSA in-situ to thrombose; complete resolution of symptoms is not guaranteed.

avoiding the potential for carotid-to-subclavian bypass failure (by direct aortic implantation).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.