-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Futoshi Morio, Shota Morimoto, Toshiya Tachibana, Tomoya Iseki, Fragility fracture of talar neck in an osteoporotic patient treated by posterior-to-anterior screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 2, February 2023, rjad029, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad029

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Fragility fractures of the talar neck are extremely rare. Here, we describe a case of fragility fracture of the talar neck associated with osteoporosis in a 76-year-old female, who was treated by posterior-to-anterior screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy. A 76-year-old female cleaner with a history of osteoporosis complained of pain in her right ankle when going downstairs. Radiological findings revealed a fragility fracture of the talar neck associated with osteoporosis. Because the patient was elderly and it was difficult to treat using a prolonged non-weight-bearing cast, we performed a posterior-to-anterior parallel dual screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy for this case. As a result, the patient was able to return to work 8 weeks after surgery without pain, dysfunction or complication. Osteosynthesis with posterior-to-anterior screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy successfully treated a rare case of fragility fracture of the talar neck in a 76-year-old female cleaner.

INTRODUCTION

The talar neck is the most common site, accounting for 50% of all talar fractures [1, 2]. Fractures of the talar neck generally occur by high-energy trauma, such as falling from a great height and traffic accidents [3]. In general, fragility fractures are caused by the repetition of low-energy trauma and are often associated with osteoporosis [4].

In terms of surgical treatment for talar neck fractures, a screw is generally inserted from the anterior part of the talus [5, 6]; insertion from the posterior section of the talus has biomechanical and anatomical advantages over anterior insertion in that it provides greater fixation and avoids chondral injury to the talonavicular joint [7, 8]. However, there have been reported risks to this approach, such as injury to the sural nerve and flexor hallucis longus (FHL), owing to a narrower safety zone for screw insertion [9].

A two-portal hindfoot endoscopic technique, described by van Dijk et al. [10] in 2000, allows direct visualization of the hindfoot structures. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of a posterior-to-anterior screw fixation used to treat a fragility fracture of the talar neck under hindfoot endoscopy.

In this report, we describe a rare case of a talar neck fragility fracture in a 76-year-old female with osteoporosis, which was treated by endoscopic posterior-to-anterior screw fixation of the hindfoot. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient before publishing this report.

CASE REPORT

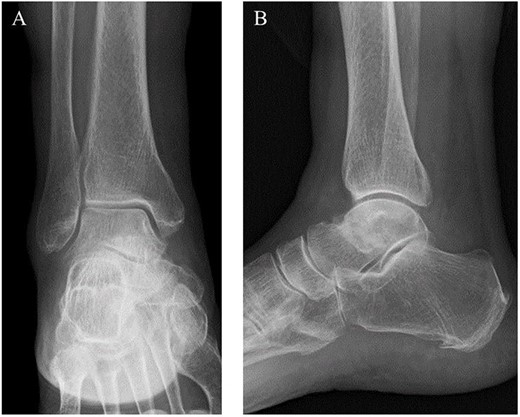

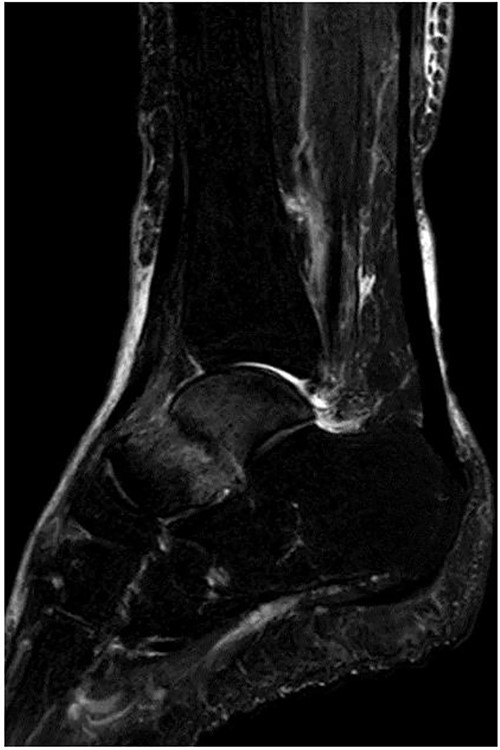

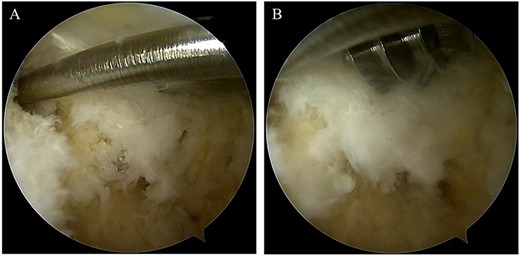

A 76-year-old female, who worked as a cleaner, complained of pain in her right ankle when going downstairs while working. She had medical history of only osteoporosis and had taking daily active vitamin D for >10 years. She was given conservative treatment for 1 month at a local clinic, however, her ankle pain persisted and so she visited our clinic. Physical examinations revealed tenderness and swelling at the anterior aspect of the ankle. Plain radiographs showed no obvious abnormal findings (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a low signal linear line in the talar neck and a bone marrow edema around the line (Fig. 2). Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) demonstrated an obvious fracture line in the talar neck, however, the bone fragment was not displaced (Fig. 3). Based on medical histories, clinical and radiological findings, we diagnosed her with a fragility fracture of the talar neck associated with osteoporosis. Because the patient was elderly and it was difficult to treat using a prolonged non-weightbearing cast, we applied operative treatment to allow early rehabilitation. The operation was performed under spinal anesthesia in a prone position with an air tourniquet and a fluoroscopy. The posteromedial and posterolateral portals were created according to van Dijk et al. [10]. First, the posterior aspect of the talus was observed using a 4.0-mm diameter 30° arthroscope, and soft tissues around the talus (including synovium and adipose tissues) were removed with a 3.5-mm diameter motorized shaver. After confirming the posterior part of the talar body and the FHL, two 1.6-mm diameter guidewires were parallelly inserted from the posterior part of the talar body to the talar head by hindfoot endoscopy and fluoroscopy (Fig. 4A), and two cannulated 4.5-mm diameter double-threaded screws (Double Thread Screw, Meira, Nagoya, Japan) were inserted through the guidewires (Fig. 4B). The wound was sutured, and the operation was concluded (Fig. 5). Active range of motion exercises were allowed immediately after surgery, and a non-weightbearing short leg splint was worn for 1 week. Partial-weight bearing was permitted at 2 weeks and full-weight bearing was permitted at 4 weeks post-operatively. In addition, daily injections of teriparatide (Forteo, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were introduced 2 weeks post-operatively. Eight weeks after the operation, the patient was able to return to work without pain or functional impairment. One year postsurgery, the patient was still working as a cleaner without any symptoms or complications.

Preoperative plain radiographs showed no obvious abnormal findings from the (A) anteroposterior and (B) lateral views.

MRI revealed a low signal linear line in the talar neck and a bone marrow edema around the line on a fat-suppressed T2-weighted (FS-T2) image.

Although a non-contrast CT scan of the sagittal view demonstrated a fracture line in the talar neck (arrow), the bone fragment was not dislocated.

(A) After confirming the posterior part of the talar body and the FHL, two 1.6-mm diameter guidewires were parallelly inserted from the posterior part of the talar body to the talar head via under hindfoot endoscopy and fluoroscopy; (B) two cannulated, 4.5-mm diameter double-threaded screws were inserted through the guidewires.

Post-operative plain radiographs revealed that two cannulated 4.5-mm double-threaded screws were inserted from the posterior part of the talus to the talar head as seen from the (A) anteroposterior, (B) lateral and (C) oblique views.

DISCUSSION

The most common mechanism of talar neck fracture is reported to be contact of the talar neck with the anterior edge of the distal tibia due to hyperdorsiflexion of the talocrural joint in high-energy trauma [3]. Previous biomechanical studies have demonstrated that the talocrural joint motion, including dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, was highest when walking downstairs [11, 12]. We attributed the cause of the fragility fracture in this case to the poor bone quality of the talar neck and hyperdorsiflexion of the talocrural joint when walking downstairs.

Fan et al. [8] have reported that the biomechanical efficiency of posterior-to-anterior parallel dual screw fixation provided better results in the stress peak, stress distribution and displacement of the talus and internal fixation. In addition, posterior-to-anterior screw fixation has an anatomic advantage of avoiding damage to the talonavicular joint.

However, posterior-to-anterior screw fixation has anatomic risks, such as sural nerve and FHL damage, due to a narrower safety zone for screw insertion [13, 14]. A two-portal hindfoot endoscopic technique provides a direct and better visualization of the hindfoot structures and is associated with fewer complication rates [11]. A very low rate of sural nerve and FHL injury has been reported with the hindfoot endoscopic technique [15]. The rates of the sural nerve and FHL injury in this report were sufficiently low when compared to the percutaneous posterior-to-anterior screw fixation for fractures of the talar neck.

In this case, it was necessary to perform a posterior-to-anterior parallel dual screw fixation in order to obtain stronger fixation. However, insertion screws in the posterior part of the talus can pose such risks such as sural nerve and FHL injuries. Therefore, in order to avoid these risks, we performed a posterior-to-anterior parallel dual screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy for this case. As a result, the patient was able to return to work 8 weeks after surgery without pain, dysfunction or complication.

In conclusion, we reported a rare case of fragility fracture of the talar neck associated with osteoporosis in a 76-year-old female, who was successfully treated by a safe and minimally invasive posterior-to-anterior screw fixation under hindfoot endoscopy. This surgical technique may be a useful option in the treatment of fragility fractures of the talar neck.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mr Nicholas Pollifrone for their assistance in editing the English manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

No funding was received.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.