-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Vysheki Satchithanandha, Ngee-Soon Lau, Ana Galevska, Charbel Sandroussi, Bouveret syndrome: two approaches one stone, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2023, Issue 10, October 2023, rjad570, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjad570

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bouveret syndrome is a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction, a consequence of a large impacted gallstone leading to the formation of a bilioenteric fistula. We present a case of a 79-year-old female who presented with a history of persistent nausea and vomiting. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large gallstone impacted in the second part of the duodenum, complicated by a cholecystoduodenal fistula, leading to gastric outlet obstruction. After nasogastric decompression, the patient underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and attempted stone retrieval which was unsuccessful. Consequently, she underwent laparotomy, gastrotomy, and extraction of the stone. This case highlights the pitfalls of managing Bouveret syndrome via an endoscopic or an open surgical approach.

Introduction

Bouveret syndrome is a cause of gastric outlet obstruction, a direct complication of bilioenteric fistula formation in the proximal duodenum or pylorus, secondary to a large impacted gallstone. It is the cause of 1%–3% of all cases of gallstone ileus and primarily affects 74-year-old females [1], with stones >2.5 cm. The treatment involves endoscopic removal of the stone or various lithotripsy techniques, which can lead to complications such as distal enteric obstruction from stone fragmentation [2]. The optimal surgical approach remains a subject of ongoing debate with some advocating for enterolithotomy alone, particularly in older populations with significant comorbidities, as the necessity for a definitive biliary procedure is low. Moreover, considering the presence of a patent cystic duct, the likelihood of spontaneous fistula closure is high. We report a case of Bouveret syndrome during which lithotripsy was avoided, and a surgical approach was undertaken after a failed initial endoscopic attempt.

Case report

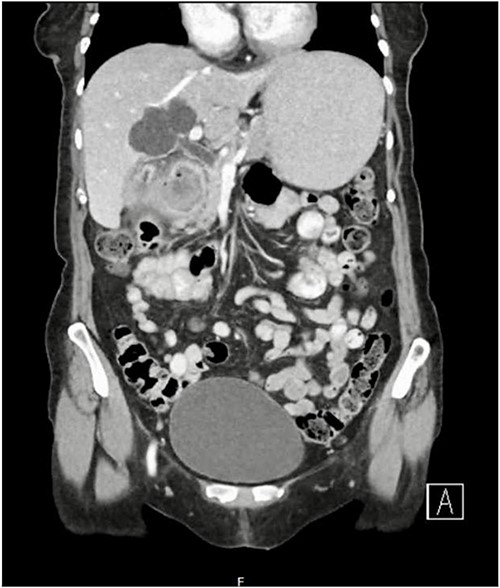

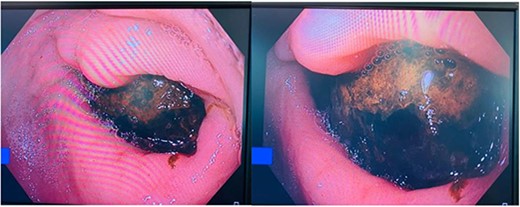

A 79-year-old female presented with a 5-day history of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort but no overt pain. She was hemodynamically stable. On examination, she had mild right upper quadrant tenderness but no signs of peritonism and a negative Murphy’s sign. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed features suggestive of acute cholecystitis, complicated by cholecystoduodenal fistula with a large (3.5 cm) gallstone impacted at the second part of the duodenum (Figs 1 and 2), consistent with Bouveret syndrome. The patient was kept fasting and a nasogastric tube was inserted for gastric decompression. She underwent a gastroscopy in an attempt to remove the impacted gallstone. However, the stone could not be retrieved due to its severe impaction, most evident on the pylorus side of the duodenum (Fig. 3).

Coronal CT image of abdomen demonstrating fistulous connection between the gallbladder and duodenum and a large gallstone.

Axial CT image of abdomen demonstrating a fistulous connection between the gallbladder and duodenum and a large gallstone.

Large gallstone in pylorus side of the duodenum on endoscopy causing complete obstruction.

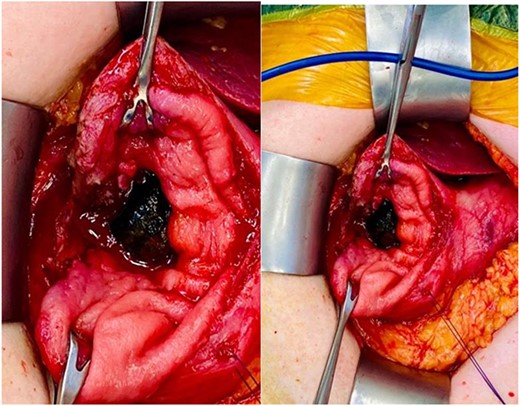

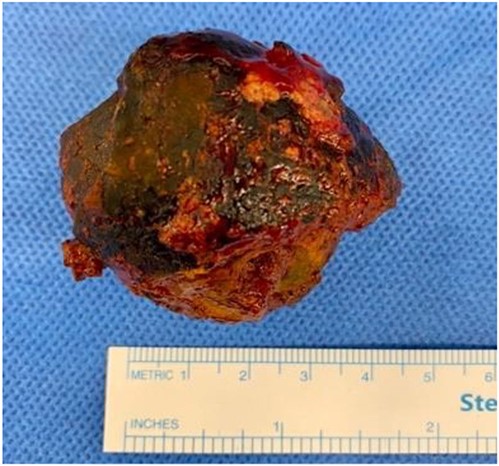

Given the unsuccessful endoscopic attempt, the decision was made to relieve the gastric outlet obstruction surgically. The patient underwent a mini laparotomy, gastrotomy, and extraction of gallstone (Fig. 4). The fistula was visualized communicating to the bile duct, and all stone fragments were retrieved through a longitudinal gastrotomy (Fig. 5). The gastrotomy was repaired with 4–0 polydioxanone (PDS), and an omentopexy was performed. The patient made an unremarkable recovery and was discharged home after 10 days.

Mini laparotomy, gastrotomy, and extraction of large impacted gallstone causing gastric outlet obstruction.

Large gallstone retrieved during laparotomy measuring up to 4 cm in diameter.

Discussion

Bouveret syndrome remains a topic of debate, in regard to its management. This case demonstrates the success of a surgical approach after initial endoscopic attempts were unfruitful. The decision to opt for direct surgical intervention over lithotripsy exemplifies the intricate clinical choices surgeons must navigate when deliberating between minimally invasive and open surgical methods.

Endoscopy and lithotripsy modalities are preferred due to their lower mortality and morbidity rates compared with surgery (1.6%–17.3%) [3]. However, endoscopic intervention has a lower success rate compared with surgical intervention (43%–94.1%) [4]. Endoscopic management frequently requires adjuncts due to complexities involved. Endoscopy alone is most effective with smaller stones (<2–3 cm) [5], as complete closure of cholecystoduodenal or cholecystogastric fistulas via endoscopy is not the norm. Furthermore it is often unnecessary [6] due to the spontaneous closure of fistulas.

Larger calcified stones (>2–3 cm) becomes challenging for endoscopic retrieval, prompting the use of lithotripsy to disintegrate the stone. However, the drawback of electrohydraulic lithotripsy lies in its potential to inadvertently focus shock waves on the intestinal wall, resulting in bleeding and perforation [7]. Laser lithotripsy offers precise energy targeting the stone with minimal tissue damage [8]. However, a significant complication of laser includes iatrogenic distal gallstone ileus due to stone fragments [9, 10]. Recent evidence shows that less than two-thirds of published cases have been successfully treated via lithotripsy [11].

Surgery has demonstrated higher success rates in the past; however, it is associated with significant morbidity (37.5%) and mortality (11%) [12]. Surgical options encompass open gastrotomy, pylorotomy, or duodenotomy, especially when endoscopy proves ineffective. These choices are employed when stones can be manoeuvred to a favourable location for extraction. In instances where open surgery encounters challenges accessing stone-impacted areas, endoscopy serves as an adjunct to reposition the stone to be more accessible for an enterotomy.

The management of Bouveret syndrome remains a personalized process of the patient’s unique circumstances. As medical advancements continue to unfold, it may further refine the approach to this rare condition.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.