-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael van der Mark, Merwe Hartslief, Massive emphysematous pancreatitis associated with duodenal microperforation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 9, September 2022, rjac392, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac392

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Emphysematous pancreatitis (EP) is a rare variant of necrotizing pancreatitis which may result from bacterial superinfection of pancreatic tissue with gas-forming organisms such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gas formation is a consequence of mixed acid fermentation by these species, which may colonize the inflamed pancreatic tissue by intestinal translocation, hematogenous spread or direct seeding by penetrating ulcer. Previously described cases of EP associated with penetrating ulcer are exceedingly rare and typified by focal emphysema confined to the site of fistulation, often the head of pancreas. We present a case of massive emphysematous pancreatitis with pseudoaneurysm involvement and associated duodenal microperforation. Furthermore, we describe the successful operative management of this patient, who remains well in the community.

INTRODUCTION

Emphysematous pancreatitis (EP) is a rare variant of necrotizing pancreatitis characterized by the presence of gas within the pancreatic parenchyma or peripancreatic collection [1, 2]. EP must be distinguished from other causes of pancreatic intraductal or parenchymal gas including endoscopic instrumentation, reflux from the duodenum after sphincterotomy, enteric fistula and end-organ infarction [3]. Gas formation results from mixed acid fermentation by gas-forming bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species, which may colonize the inflamed pancreatic tissue by intestinal translocation, hematogenous spread or direct seeding by penetrating ulcer.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department of a regional hospital with acute onset abdominal pain at 0830 following a large alcohol binge the prior evening, in the context of known chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. Prior history included workup for a head of pancreas mass believed to be non-neoplastic in nature, as well as open splenectomy, schizophrenia and rheumatic heart disease. There was no history of regular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use.

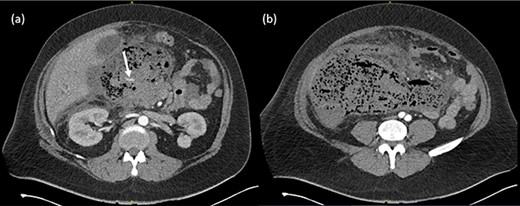

He was hemodynamically stable and afebrile on presentation, however deteriorated rapidly with tachycardia (HR140), hypotension (<100 mmHg systolic) and temperature of 39.0°C. Examination revealed a grossly distended, rigid abdomen. Inflammatory markers were elevated with a white cell count of 35.3 × 109/L and C-reactive protein of 326 mg/L. Serum lipase was 384 U/L. Imaging demonstrated a large peripancreatic collection with extensive gas loculations and active arterial blush and he was taken for emergent surgery (Fig. 1).

(a) Arterial phase CT axial view demonstrating peripancreatic collection with extensive gas loculations and active arterial blush (white arrow). (b) Extensive peripancreatic collection at the level of the aortic bifurcation.

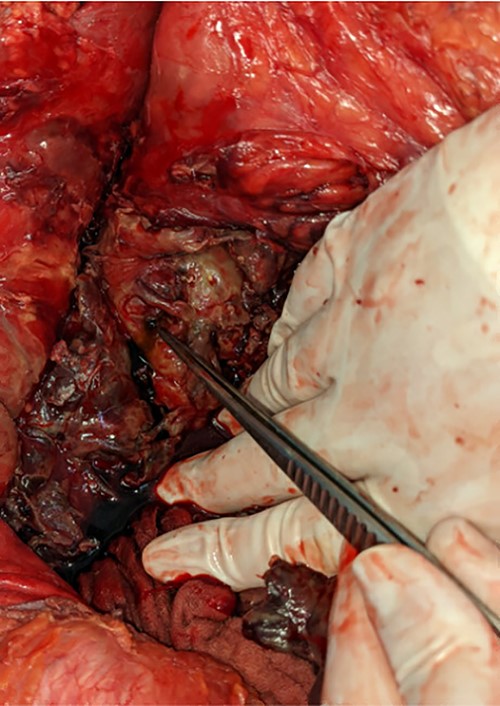

Midline laparotomy revealed an infected retroperitoneal hematoma of ∼3 L in volume.

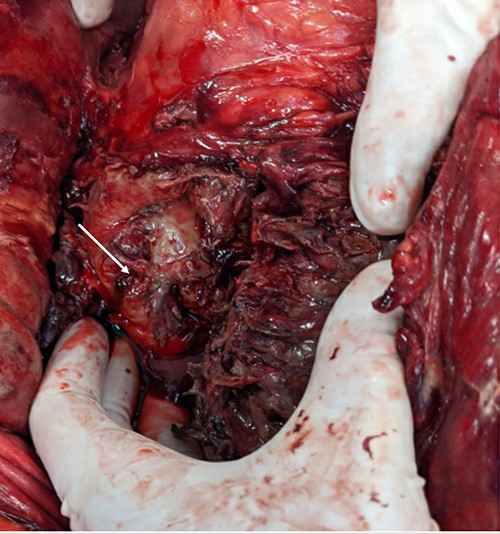

A pinpoint perforation at the junction of the first and second duodenal segments was identified, with no other perforations identified both by gross examination and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD). Parts of the omentum and mesenteric fat of the left retroperitoneum appeared saponified. An additional bile-stained phlegmon adjacent to the pancreas was noted in conjunction with a firm head of pancreas mass and additional tail of pancreas pseudocyst (Figs 2 and 3).

The gallbladder and stomach appeared normal.

OGD confirmed one non-bleeding cratered 10 mm duodenal ulcer with adherent clot at the junction of the first and second portion of the duodenum. A nasojejunal tube was placed.

Intraoperative swab of the hematoma sent and blood cultures both demonstrated mixed anaerobic bacteria and grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. Testing of the purulent pseudocyst fluid showed lipase of 61 700 U/L.

After extensive drainage of the hematoma, the right retroperitoneum was opened and right colon mobilized. A 14-Fr T-tube was placed into the duodenal perforation, a right upper quadrant drain was placed and abdominal vacuum-assisted closure dressing applied. Relook laparotomy at 48h demonstrated omental necrosis and a leak around the t-tube. The tube was removed and defect closed primarily, with decision made not to undertake patch repair due to omental necrosis. Multiple further debridement and washouts were required in the subsequent 4-month admission period, along with pancreatic drain placement, culminating in abdominal closure by split skin graft. The patient remains well in the community.

DISCUSSION

Previously described cases of EP associated with penetrating ulcer are exceedingly rare and typified by focal emphysema confined to the site of fistulation, often the head of pancreas [4]. We speculate that erosion into branches of the gastroduodenal artery and resulting ruptured pseudoaneurysm may account for the anomalous volume of this collection.

Despite the rarity of EP, bacterial superinfection is estimated to occur in 40% of patients with necrotizing pancreatitis [5, 6]. Mechanisms of bacterial superinfection are multiple: increased intestinal mucosal permeability secondary to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) facilitates the translocation of intestinal flora, and in this case may have preceded any direct seeding by penetrating ulcer, hematogenous or lymphatic spread.

The gas-forming organism K. pneumoniae is one of the most commonly implicated pathogens alongside E. coli [6] . A specific mechanism for gas formation in EP has yet to be proposed but may be analogous with other intra-abdominal foci including gas-forming pyogenic liver abscess. In this process, Enterobacteriaceae and Klebsiella species generate energy by the mixed acid (formic acid) fermentation of glucose [7]. The formate produced in mixed acid fermentation is relatively stable at an alkaline pH, however at a pH of 6 or less gas-forming microorganisms produce formic hydrogenylase, which converts formic acid to CO2 and H2 [7]. Therefore, the relatively alkaline environment produced by pancreatic excretions (pH 7.8–8.5) may account for the rarity of EP despite the frequency of colonization with gas-forming organisms in necrotizing pancreatitis.

The average mortality of infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP) is estimated at 30%, ∼triple the rate of death in sterile ANP [8, 9]. However, the prognostic significance of EP remains a matter of debate. Recent work by Li et. al suggests that earlier appearance of pancreatic gas (within 2 weeks of disease onset) is associated with older patients, glycemic dysregulation and carries significantly higher mortality risk (57.1 vs. 8.7%) when compared with later onset EP [10].

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Written consent was obtained from the patient before submission.

Thank you to Dr. Amy Lawson for capture of operative images.