-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Muhammad H Mirza, Emeka Nzewi, A rare case of small bowel arteriovenous malformation presenting as obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 6, June 2022, rjac278, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac278

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (LGIB) is a common surgical condition, which is frequently encountered in the emergency department. The most common origin of LGIB is from the colo-rectal region. However, in majority of cases where no apparent bleeding source is identified, small bowel is the area of concern. Here, we report an uncommon cause of small bowel bleeding that manifested as LGIB. A 63-year-old woman presented to emergency department with 2-day history of dark red rectal bleeding. The upper and lower GI endoscopy did not reveal any source of bleeding. Due to the ongoing blood loss, the hemoglobin level dropped significantly, necessitating blood transfusion. Subsequently, an emergency computed tomography mesenteric angiogram was performed, which showed extravasation of contrast into the distal ileum. She underwent a laparotomy where an arteriovenous malformation of the ileum was noticed. A limited ileal resection was performed, followed by primary anastomosis. She recovered well post-operatively with no further bleeding.

INTRODUCTION

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (LGIB) is a common surgical condition, which is frequently encountered in the emergency department. Anatomically, it has been differentiated from upper GI bleeding by the location of the source of bleeding, which is found distal to the ligament of treitz [1]. The most common cause of LGIB is diverticulosis, according to a large systematic review of studies involving patients of acute LGIB, followed by ischemic colitis and various anorectal conditions [2]. In ~5% of cases, no source is found with traditional upper and lower GI endoscopy. Approximately, 75% of such cases have the origin of bleeding in the small bowel [3]. Here, we report an uncommon cause of small bowel bleeding that manifested as LGIB.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old lady presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of rectal bleeding. She was passing dark blood, with no associated GI symptoms. Her bowel habits were previously normal. Her past medical history was significant for dyslipidemia, nephrolithiasis, depression, appendicectomy and cesarean sections. She was not taking any anticoagulants. On examination, she was hemodynamically stable, and her abdominal examination revealed mild lower abdominal discomfort on deep palpation. There were no signs of organomegaly. Examination of the perianal region showed few skin tags, and blood was noticed on per-rectal examination. The systemic examination was normal.

Full blood count showed a hemoglobin level of 11.9. Remaining blood investigations, urinalysis and radiographs of chest and abdomen were normal. She underwent an urgent gastroscopy, which showed some reflux esophagitis and duodenitis. However, no stigmata of bleeding were apparent. As she remained hemodynamically stable, she received bowel preparation and underwent a colonoscopy 48 hours later, which did not show any active source of bleeding. However, blood was noticed throughout the colon and in terminal ileum, hinting at small bowel as the primary source of bleeding.

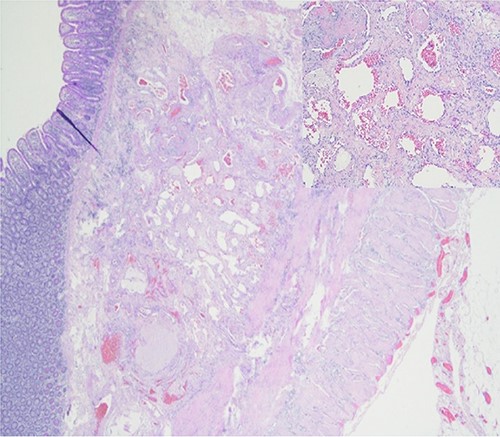

Further episodes of rectal bleeding were noticed the following day, and the hemoglobin level dropped significantly, requiring blood transfusions. An urgent computed tomography (CT) mesenteric angiography was performed, which demonstrated the extravasation of contrast in a segment of distal ileum (Fig. 1), ~30 cm from the ileocecal valve, suspicious for angiodysplasia. She subsequently underwent a laparoscopy, which was converted into a lower-midline laparotomy due to dense omental adhesions secondary to prior appendectomy and cesarean sections. After adhesiolysis, small bowel was thoroughly examined. The terminal ileum contained blood, while proximal small bowel appeared unremarkable. About 30 cm from the ileocecal valve, a small transmural lesion was noticed, which was red and blanching in appearance (Fig. 2). A segmental resection of ileum was performed, and the specimen was cut open to demonstrate the luminal aspect of AVM (Fig. 3). A primary anastomosis was performed. Histology showed a small, non- encapsulated nodule, composed of complex clusters of thin and thick-walled blood vessels, abnormally located in the submucosa (Fig. 4). Post-operatively, the patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home well after 4 days.

CT mesenteric angiogram showing contrast extravasation in distal ileum.

Resected ileal segment showing luminal aspect of AVM, indicated by white arrow.

DISCUSSION

Small bowel bleeding, previously described as obscure GI bleeding, is the underlying etiology of acute lower GI hemorrhage in around three-quarter of cases, where no obvious source is localized on endoscopic examination [3]. American Gastrointestinal Association delineates the causes of small bowel bleeding according to age, where patients younger than 40 years are likely to have inflammatory bowel disease, Meckel’s diverticulum or a small bowel neoplasm, while older patients have vascular lesions or mucosal erosion/ulceration [4]. Although routine endoscopic evaluation is usually negative in small bowel bleeding, presence of blood in the terminal ileum is an independent risk factor, indicative of a small bowel source [5].

American college of Gastroenterology guidelines suggest Video Capsule Endoscopy (VCE) as the investigation of choice for the evaluation of small bowel bleeding. However, an emergency angiography has been suggested for unstable patients with acute, obvious GI bleeding [6]. Akabane S. et al. reported a case of small bowel bleeding secondary to an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), which was treated by laparoscopic segmental resection [7]. They also suggested preoperative localization of lesion, by tattooing using double-balloon endoscopy, to aid in the surgical resection.

A similar case of 69-year-old male was reported from Maebashi, Japan, who presented with GI bleeding and transfusion-dependent anemia. Double-balloon enteroscopy revealed a polypoid, submucosal mass in the distal ileum, which was subsequently resected laparoscopically, and a diagnosis of AVM was confirmed by histological examination [8]. In our case, however, facility of double-balloon enteroscopy was not available onsite and a CT mesenteric angiogram was a more feasible option, which proved equally useful. Endoscopic treatment, such as electrocoagulation, is a proven management option of dealing with intestinal angiodysplastic lesions. However, a study from MA clearly showed the efficacy of surgical treatment in terms of re-bleeding over medical and endoscopic treatment [9]. Nonetheless, as stressed by Saurin et al., large, randomized studies are essential to demonstrate the efficacy of one treatment modality over another for safe and effective patient management [10].

CONCLUSION

Small bowel bleeding is a frequent underlying etiology in patients of LGIB, where initial endoscopic examination is normal. VCE is the gold standard for investigating stable LGIB patients, while CT mesenteric angiography is indicated for evaluation in relatively unstable patients, while surgical resection is required for definite hemorrhage control and concrete diagnosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

- congenital arteriovenous malformation

- computed tomography

- hemorrhage

- endoscopy

- gastrointestinal bleeding

- anastomosis, surgical

- blood transfusion

- emergency service, hospital

- extravasation of diagnostic and therapeutic materials

- intestine, small

- laparotomy

- surgical procedures, operative

- ileum

- lower gastrointestinal bleeding

- rectal bleeding

- distal ileum

- hemangioma, arteriovenous

- hemoglobin measurement

- mesenteric arteriogram

- ileectomy