-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lina Cadili, Noelle L Davis, A unique case of free-floating gastric band tubing causing intraabdominal sepsis in a patient with locked-in syndrome secondary to Guillain–Barré syndrome, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 3, March 2022, rjac081, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac081

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is a known bariatric procedure that has largely fallen out of favor in our modern surgical era. Several case reports describe various complications secondary to gastric band slippage. Here we present a unique complication not related to gastric band slippage, but intraabdominal sepsis secondary to free-floating gastric band tubing after removal of the subcutaneous port in a patient with locked-in syndrome secondary to Guillain–Barré syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) is a bariatric procedure that has been supplanted by other procedures due to its limited success in maintaining weight loss and associated morbidity [1]. Several case reports have documented complications from a slipped gastric band including gastric erosion, gastric necrosis and hemorrhage and gastric volvulus [2–4]. We present a unique case of intraabdominal sepsis secondary to free-floating gastric band tubing after removal of the subcutaneous port in a patient with locked-in syndrome.

CASE

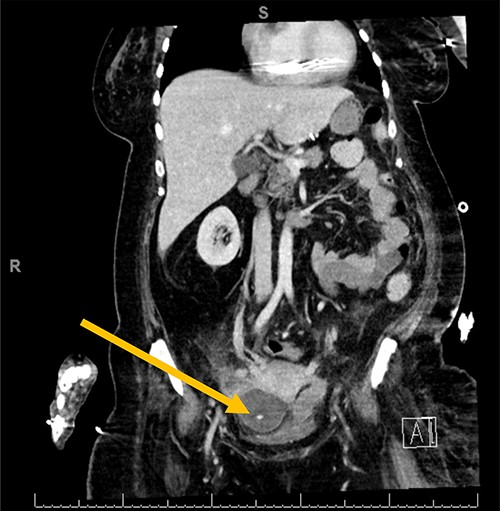

The patient is a 54-year-old woman with locked-in syndrome, which is complete paralysis of all voluntary muscles excluding those that control ocular movements, secondary to Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS) who had a laparoscopic adjustable gastric band placed in 2008. A few months prior to her presentation to the emergency department, the subcutaneous port of the band was removed by her care team without consultation from a surgery team, as the skin site appeared to be infected. Of note, the tubing was left in situ. The patient presented to the emergency department with generalized abdominal discomfort for 1 week associated with fevers noted by her caregivers. Upon admission, she was resuscitated and treated with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. A computerized tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a pelvic abscess around the tip of the gastric band tubing (Fig. 1). She did not improve after 5 days of medical management; therefore, the patient was consented for surgical removal of the gastric band and tubing.

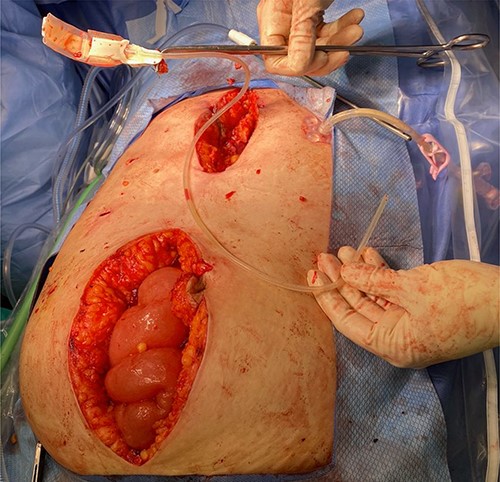

Diagnostic laparoscopy was initially carried out in hopes of identifying and removing the gastric band. However, adequate pneumoperitoneum was difficult to achieve due to minimal response to paralytic agents with increasing dosages presumably secondary to the patient’s underlying disease. As such, the decision was made to convert to laparotomy. A lower midline incision was made. The gastric band tubing was noted coursing over the ascending colon. This was traced down into the pelvis and an abscess cavity containing a large amount of purulent fluid was encountered. A swab of the fluid was sent for culture and sensitivity and the fluid, and it was then carefully suctioned and irrigated. In order to remove the gastric band, a separate upper midline laparotomy incision was made. Careful dissection was carried out until we were around the gastric band; its anchoring sutures were cut, and the band was freed from around the stomach. Interestingly, the band itself appeared to be infected and had a foul odor. The band along with the tubing was removed from the surgical field (Fig. 2). A Jackson–Pratt drain was placed in the pelvis to facilitate further drainage post-operatively. The patient tolerated the procedure well, her gastrostomy tube feeds were restarted on POD 1 and she had an uneventful recovery.

DISCUSSION

LAGB has fallen out of favor in our modern surgical era. There are several documented complications secondary to slippage of the gastric band. In this patient’s case, there seemed to be lack of familiarity and knowledge regarding the mechanism of the band inflation from the subcutaneous port. As such, our patient unfortunately had her subcutaneous port removed as her caregivers were not aware of the subsequent consequence of the gastric tubing being floating freely in the abdomen. This case presents a good example of the importance of liaising with appropriate medical or surgical services for advice regarding management of devices that may be unfamiliar.

In addition, this case poses an interesting anesthetic challenge given the patient’s lack of response to paralytic agents. The literature regarding patients with GBS and lack of response to paralytic agents is scarce. It is known that succinylcholine should be avoided in these patients due to the risk of hypokalemia, and the use of non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents in patients with GBS presents risk of prolonged blockade that leads to prolonged ventilatory support post-operatively. Also, there is no basis in the literature for the use of sugammadex in patients with GBS [5]. Further research regarding paralytic agents in GBS patients is required.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.