-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

José J Ceballos-Esparragón, María José Servide-Staffolani, Patrizio Petrone, Missed traumatic abdominal injury with challenging management: report of 12-year follow-up, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 3, March 2022, rjac053, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjac053

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Despite well-established clinical guidelines and use of radiologic imaging for diagnosis, challenges are faced when accurate decisions must be made within seconds. Patients with life-threatening injuries represent 10–15% of all hospitalized trauma patients. In fact, 20% of abdominal injuries will require surgical intervention. In abdominal trauma, it is important to distinguish the difference between surgical intervention, which includes damage control procedures and definitive treatment. The main objective of damage control surgery is to control the bleeding, reduce the contamination and delay additional surgical stress at a time of physiological vulnerability of the patient, along with abdominal containment, visceral protection and avoiding aponeurotic retraction in situations where primary abdominal closure is not possible. However, this technique has high morbidity and comes with a myriad of complications, including development of catastrophic abdomen and formation of enterocutaneous fistulas.

INTRODUCTION

The management of the severe trauma patient has always been a challenge for the general surgeon. The delay in diagnosis and treatment of abdominal injuries is one of the most frequent causes of avoidable death in both blunt and penetrating trauma to the abdomen [1]. This clinical case describes the management of a patient with a catastrophic abdomen after missed injuries, requiring complex surgical management in a staged approach with a subsequent successful outcome.

CLINICAL CASE

A 25-year-old female patient was transferred to the Emergency Department after sustaining a head-on motor vehicle collision. The patient was located in the center rear passenger seat with a single transverse band seat belt. On initial presentation, the patient was hemodynamically stable with a patent airway and a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15. A Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma (FAST) scan performed demonstrated a small maount of perisplenic and pelvic fluid: no solid organ injury or pneumoperitoneum. Additional computerized tomography showed lower left rib fractures (7th–11th) and compression fractures with anterior wedging of L1 and L2 as well as transerve process fracture of the same vertebra levels.

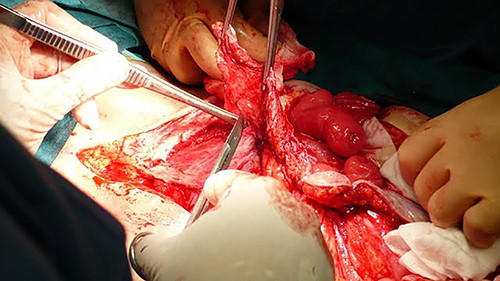

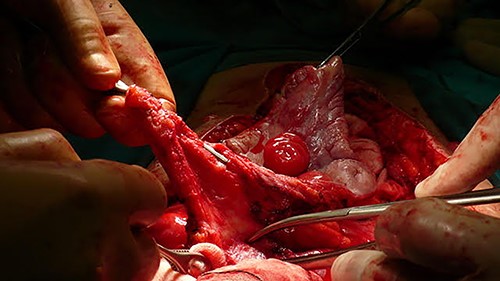

Initially, the patient was managed conservatively and admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). On the third day of admission, she became acutely hemodynamically unstable, physical examination findings concerning for an acute abdomen, with a repeat FAST scans showing increase in free intraperitoneal fluid; the running diagnosis was septic shock. After this finding and in view of clinical deterioration, the patient was taken back to the operative theater upon which exploration revealed retroperitoneal hematoma in bilateral Zone II, steatonecrosis plaques throughout the peritoneal cavity, incomplete jejunal laceration 40 cm from the Treitz angle, a complete section of the pancreas at the body-tail level with peripancreatic hematoma and necrohemorrhagic pancreatitis. The patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, jejunal enterorraphy and was left with an open abdomen (Fig. 1).

An open abdomen management begins where ~40 interventions were performed. As a consequence, the patient developed a catastrophic abdomen with numerous complex enterocutaneous fistulas. The management of the catastrophic abdomen was carried out in an artisanal way as negative pressure systems were not available at that time, using aspiration probes and placement of Goretex™ mesh (Fig. 2) and linitud films to protect the abdomen from intestinal content. The patient progressed favorably. Due to the multiple established enterocutaneous fistulas, the physiological behavior was that of a patient with a short-gut síndrome (Figs 3 and 4), so she was discharged with home parenteral nutrition, after 3 months in the ICU and 4 months of admission in the ward.

Management with aspiration probes and placement of Goretex™ mesh.

Abdomen closed by secondary intention with eviscerated loops and enteroatmospheric fistulae (front view).

Abdomen closed by secondary intention with eviscerated loops and enteroatmospheric fistulae (side view).

Intraoperative image of monobloc resection of enterocutaneous fistulas in reconstruction surgery.

Intraoperative image of monobloc resection of enterocutaneous fistulas in reconstruction surgery.

Intraoperative image of monobloc resection of enterocutaneous fistulas in reconstruction surgery.

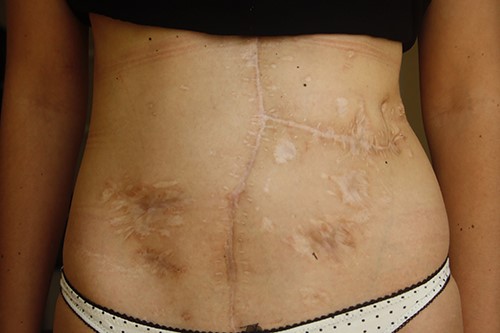

An important aspect was raised regarding the strategy of abdominal reconstruction, particularly in choosing the right moment for it given the severe picture of adhesions and a second intention granulated abdomen. There was no consensus in the literature consulted at that time, only reports that mentioned between 3 and 6 months. Our team decided to do it 1 year after hospital discharge. The patient was then admitted for elective surgery to re-establish the intestinal transit after a study to identify the different fistulous openings and to reconstruct the abdominal wall with the support of the Plastic Surgery Service (Figs 5–7). An en bloc excision of the midlaparotomy scar, subtotal colectomy up to the descending-sigmoid junction, with resection of the intestinal ileostomy and excision of three segments of the small intestine that fistulized to the wall was performed. The reconstruction of the intestinal transit was performed using four anastomoses, three mechanical latero-lateral entero-enteric anastomosis and one mechanical lateral-lateral ileosigmoid anastomosis. Due to the great retraction of the ends of the abdominal wall that prevented the separation of components reconstruction, it was decided to repair the abdominal wall by means of permacol mesh plasty and a wide skin flap. The patient was discharged on Day 16 without complications (Fig. 8). She has been undergoing follow-up control for 12 years after her discharge (Fig. 9), without incidents to date.

DISCUSSION

Trauma is considered as severe if it has an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 15 or greater. Most patients with an ISS greater than 25 experience multisystem organ injury. This classification can be helpful in assessing possible inadvertent injuries during the secondary assessment [1].

It is vitally important for the surgeon to know the mechanism of injury and the characteristics of the traumatic event. Patient evaluation in trauma necessitates a systematic approach. In this case, the delay in the diagnosis of her abdominal injury did not result in death but rather a torpid evolution that required complex management of a catastrophic abdominal injury.

Besides its benefits [2–6], open abdomen management also carries a high rate of morbidity due to the formation of an enterocutaneous fistula and giant eventrations [7]. Negative pressure systems stabilize the abdominal wall by uniformly transmitting mechanical forces to the surrounding tissue without creating stress on the wound edges; it controls the loss of fluids and reduces the retraction of the fascia [8, 9], and by eliminating excess exudate, it favors the healing and closure of wounds in a much faster way [3].

It is important to note that at the time this, case was treated and, in our environment, such vacuum systems were not available. Despite this, the patient presented a satisfactory final evolution using conventional healing methods, creating artisan vacuum systems thanks to which it was possible to externalize the fistulous discharge, thus avoiding a fatal outcome, not only due to the severity of the injuries caused by the accident but by the numerous complications suffered as a result of it.

The following conclusions are drawn from this case report: (i) training in trauma for the management of this type of injury is essential for the correct and timely diagnosis; (ii) knowledge of the pathophysiology of the trauma and the mechanism of injury as a high indicator of suspicion of injuries; (iii) the need for training in the management of open abdomen and catastrophic abdomen; (iv) this type of clinical case must have the same surgeon who coordinates its daily management and (v) the importance of teamwork and multidisciplinary support in complex cases.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

Authors' own resources.