-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hirotaka Kumeda, Gaku Saito, Spontaneous pneumomediastinum diagnosed by the Macklin effect, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, rjab634, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab634

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Vomiting-induced pneumomediastinum is often caused by oesophageal perforation or alveolar rupture due to increased pressure. A correct diagnosis is important because both diseases have different treatments and severities. We report the case of a 21-year-old man who presented with chest pain and fever after frequent vomiting and had elevated white blood cell counts on blood tests. There was extensive pneumomediastinum, and the lower oesophagus was swollen and thickened on chest computed tomography. An oesophagram was not possible due to severe nausea and vomiting. Accumulation of free air was found along the peripheral bronchi or the pulmonary vascular sheath in the left lower lobe, which was continuous with the mediastinum. Based on the presence of the Macklin effect, we diagnosed a pneumomediastinum with a high possibility of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. The Macklin effect is a finding that can likely distinguish oesophageal perforation from spontaneous pneumomediastinum.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is described as free air located within the mediastinum that is not associated with any noticeable cause, such as chest trauma, intrathoracic infections, surgery, other organ rupture or mechanical ventilation. Its pathophysiology involves the rupture of the alveoli due to a rapid increase in alveolar pressure, followed by the accumulation of free air along the sheath of the bronchi or pulmonary vessels, which is known as the Macklin effect [1]. This occurs because the pressure in the mediastinum is lower than that in the lung periphery. SPM often develops in young adults and usually resolves spontaneously within a few days of treatment, including rest and analgesics [2]. On the other hand, oesophageal perforation is the most serious gastrointestinal tract perforation and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have reported that 83.5% of patients with oesophageal perforations have pneumomediastinum [3]. Therefore, it is important to distinguish SPM from oesophageal perforations. We report a case of SPM in which the chest computed tomography (CT) finding of the Macklin effect was useful in distinguishing it from oesophageal perforation.

CASE REPORT

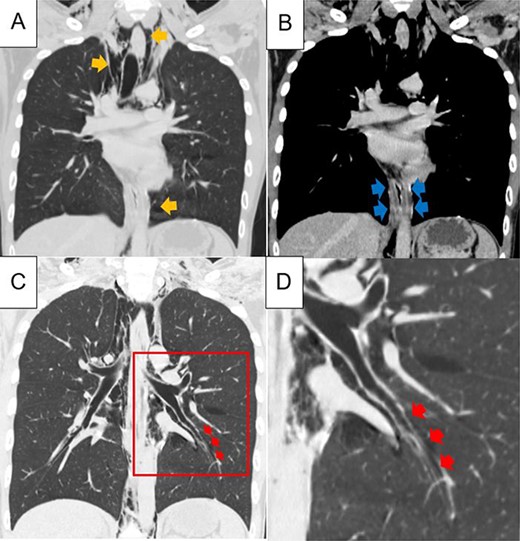

A 21-year-old man with chest pain and nausea was referred to our hospital. He had a history of admission to a psychiatric hospital with severe psychogenic vomiting. This time, he had multiple episodes of vomiting the previous day and also developed chest pain and fever of up to 38.2°C. Subcutaneous emphysema was present in the neck. Blood tests revealed a white blood cell count of 16 200 /μl. Chest CT showed extensive pneumomediastinum from the pharynges to the retroperitoneal space (Fig. 1A). The lower oesophagus was swollen and thickened, but no large wall defects, perforations or fluid collection were observed (Fig. 1B). An oesophagram was attempted to rule out oesophageal perforation, but this was not possible due to severe nausea and vomiting. Careful examination of the CT scan revealed accumulation of free air along the peripheral bronchi or pulmonary vascular sheath in the left lower lobe, which was continuous with the mediastinum (Fig. 1C, D). Based on the findings of this Macklin effect, we diagnosed that the pneumomediastinum had a high likelihood of being an SPM from the periphery of the lung rather than from oesophageal perforation. After admission, antibiotics, antipyretics and antiemetics were administered intravenously. On Day 6 after admission, the vomiting symptoms had improved, and he started eating and was discharged on Day 11. Chest CT performed on Day 15 confirmed a marked reduction of the emphysema from the neck to the mediastinum. One year later, the patient was asymptomatic and had no recurrence of SPM.

Chest computed tomography showing extensive pneumomediastinum (A; yellow arrows); the lower oesophagus is swollen and thickened, but no large wall defects or perforations and fluid collection are observed (B, blue arrows); in the left lower lobe of the lung, accumulation of free air, a finding of the Macklin effect, is found along the peripheral bronchi or pulmonary vascular sheath, which is continuous with the mediastinum (C, D; red arrows); figure D shows a magnified view of the red squares in Figure C.

DISCUSSION

SPM was first described by Hamman in 1939 [4]. More recently, it was defined as pneumomediastinum that occurs suddenly without surgery, trauma, other organ rupture or mechanical ventilation [2]. The pathophysiology of SPM has been described by Macklin et al. [1]. The Macklin effect is a phenomenon whereby a large pressure gradient between the alveoli and the lung interstitium induces alveolar rupture, leading to the subsequent accumulation of free air that course towards the mediastinum along the sheath of the bronchi or pulmonary vessels. This occurs because the pressure in the mediastinum is lower than that in the lung periphery. Once in the mediastinum, the air decompresses into the cervical space, soft tissues or even the retroperitoneal space. Several cases have reported that emphysema, which suggests the Macklin effect, helps diagnose SPM [5, 6].

Oesophageal perforations are the most serious gastrointestinal tract perforations and are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, ranging from 10 to 50% [7]. Sohda et al. [3] reported that vomiting was the most frequent cause of oesophageal perforation, with the lower oesophagus being the most common site of perforation. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, oesophageal perforation requires rigorous treatment, and emergency surgery is often indicated. In contrast, SPM can be managed conservatively by treatment with rest, reassurance and analgesia. Therefore, early definitive diagnosis is important. Among patients with oesophageal perforation, 83.5% have pneumomediastinum, which is associated with high sensitivity but poor specificity [3, 8]. Some previous reports have reported that the presence of mediastinal fluid strongly suggests oesophageal perforation [9]. There is no clear consensus on the value of rigid or flexible esophagoscopy for the diagnosis of oesophageal perforation as some authors have expressed concerns about converting small leaks into larger uncontained leaks [10, 11].

Our patient had chest pain and fever after frequent vomiting. He also had elevated white blood cell counts on blood tests. There was no mediastinal fluid, but there was extensive pneumomediastinum. Moreover, the lower oesophagus was swollen and thickened on chest CT. Unfortunately, oesophagography was not possible because of severe nausea and vomiting. Fortunately, the patient improved with antibiotic treatment and rest. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of patients with oesophageal perforation showing accumulation of free air along the peripheral sheath of the bronchi or pulmonary vessels. The Macklin effect is said to occur because the pressure in the mediastinum is lower than that in the lung periphery. Therefore, it is unlikely for the air that accumulates in the mediastinum to spread to the periphery of the lung parenchyma.

In conclusion, our patient showed Macklin effect findings and improved without developing mediastinitis. This suggests that the findings of the Macklin effect on CT are more likely to be diagnosed as SPM, and there may be no need to perform invasive examinations such as oesophagography and endoscopy. The Macklin effect is likely to be one of the findings that can distinguish oesophageal perforation and SPM.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.