-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Damini Kesharwani, Sohini Samaddar, Aruni Ghose, Nicolas Pavlos Omorphos, A silent giant staghorn renal calculus managed successfully with open pyelolithotomy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, rjab601, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab601

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Staghorn calculi (SC) are associated with high morbidity and mortality; therefore, meticulous planning is required to minimize complications. In this case report, we will discuss the management of a giant right-sided SC (~ 8 cm in diameter), which was incidentally found in a 40-year-old male, who presented with left-sided renal colic symptoms with no associated renal impairment. This case was further complicated by multiple smaller calculi surrounding the giant SC. Hence, open surgery was preferred to minimally invasive techniques. The patient underwent an uncomplicated right-sided open pyelolithotomy for his staghorn calculus and was calculi free at 1-month follow-up. His renal function returned to normal levels, highlighting effective management of the stones.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary calculus (UC) is one of the most common urological presentations to the emergency department [1]. Staghorn calculi (SC), a type of UC, occupy the majority of the renal collecting system including at least two of the renal calyces along with the renal pelvis. This can often lead to loss of renal function and parenchyma along with urosepsis. Unsurprisingly, they are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates [2].

Traditionally, the gold standard for treating SC has been open surgery (OS) in order to alleviate obstruction, improve kidney function and correct anatomical abnormalities [2]. With the advent of lower risk, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) such as endoscopic shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL), percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and ureterorenoscopy and stone removal, only 1–5.4% of patients with complex calculi are treated [3]. Although PCNL has evolved into a principal mainstay of large SC removal, it can potentially complicate into interruption of pelvicalyceal stem, bowel perforation or even hemorrhage [4]. In this case report, we describe an unusual case of an incidental giant SC, which was managed withOS.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old male presented with a 2-week history of left-sided colicky pain. It was sudden in onset, moderate in severity, gradual in progression, radiating from loin to groin, relieved by analgesics and without any associated haematuria or fever. There was no history of comorbidities, renal stones or urological procedures.

On general examination, there was no evidence of pallor, edema or lymphadenopathy. On systemic examination, the abdomen was soft, non-tender and without any palpable mass. Bilateral renal angles were free. His vital signs were within normal limits.

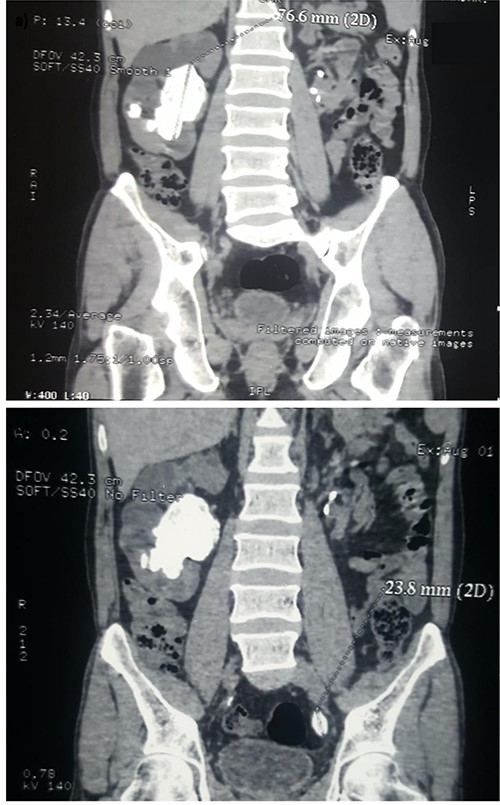

Ultrasound of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (USS KUB) revealed a 2 cm calculus in the left lower ureter with proximal hydroureteronephrosis along with an incidental giant SC, measuring ~8 cm in its largest dimension, occupying the right renal pelvicalyceal system. The SC was surrounded by multiple smaller calculi. A plain X-ray KUB confirmed these findings (Fig. 1). Because of the complexity of this case, a non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) of the abdomen was performed to further demarcate the anatomy for perioperative planning (Fig. 2a and b).

Plain X-ray KUB displaying a giant right-sided staghorn calculus surrounded by smaller secondary calculi along with a 2 cm calculus located in the distal third of the left ureter, at the inferior border of the sacroiliac joint.

Coronal view of a non-contrast CT scan demonstrating (a) a 77.6 mm staghorn calculus occupying the right renal pelvis, surrounded by smaller calculi and (b) a 23.8 mm solitary calculus in the left distal ureter.

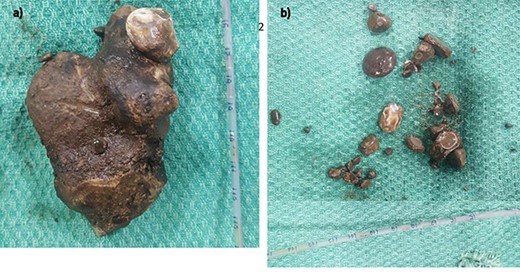

On pre-operative workup, his baseline investigations were within normal limits. Serum urea and creatinine were 23 and 1.1 mg/dl, respectively. His urine cultures showed no growth of organisms. After explaining the risks and benefits associated with OS and gaining an informed consent, we performed a right-sided open extended pyelolithotomy with simultaneous left-sided open ureterolithotomy to retrieve all stones in one sitting. The surgery was uncomplicated and the right-sided incision was ~6 cm long. The SC was removed in one piece, along with numerous smaller calculi (Fig. 3a and b). Post-operative recovery was uneventful.

Photographic evidence of (a) the staghorn calculus being removed in one piece and (b) the smaller secondary calculi surroundingit.

Our patient was asymptomatic and without any residual calculi on ultrasound at 1-month follow-up. His surgical wounds were healthy, and serum urea and creatinine were 24 mg/dl and 1.0 mg/dl, respectively.

DISCUSSION

UC has a global prevalence of 14% and a lifetime recurrence rate of 10–75% [1]. In Asia, the prevalence is ~1–5% [5]. In India, urolithiasis of the upper urinary tract prevails among 12% of the general population [1, 5]. SC initially comprised 10–15% of all UC worldwide. Thanks to early and efficacious management strategies, it has now decreased to 4%, primarily in developed nations [5, 6]. Usually, males are predominantly affected by UC, whereas SC is more prevalent in females, occurring unilaterally [6].

The sensitivity and specificity of USS KUB in the diagnosis of renal and ureteric calculi are 45 and 88% and 45 and 94%, respectively [5]. Being economical and devoid of radiation, it is an optimal initial diagnostic modality. The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines recommend that NCCT of the abdomen is the investigation of choice in patients presenting with acute flank pain or suspected ureteric stone. It can provide additional information required for perioperative planning such as diameter and density of the calculi [5]. Our diagnostic workup included ultrasound, X-ray and NCCT ofKUB.

Renal function including serum electrolytes and creatinine levels is significant in UC workup. Further quantitative assessment via renal scintigraphy may be warranted in large SC [7]. Patients with a negligible renal function (<10%) should be considered for a nephrectomy. Our patient’s pre-operative renal function was normal, and hence no further scan was performed.

SC are associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) in 49–68% of patients [6]. Urease-producing microbes such as Proteus mirabilis most frequently identified followed by Klebsiella pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter [5, 6]. Urine culture data prior to surgery is tantamount to judicious antimicrobial prophylaxis. Samples may be obtained through sterile catheterization or aspiration of the bladder preoperatively [4]. Our patient had no previous history of UTIs and a urine culture, which grew no organisms.

Conservative management of SC has a 28%, 10-year mortality rate and 36% risk of progression to significant renal dysfunction [6]. Surgical treatment is therefore the preferred modality—OS as well as MIS including PCNL monotherapy, ESWL monotherapy, a combination of PCNL and ESWL. The EAU and American Urological Association recommend PCNL as the modality of choice for large calculi (size >2 cm), with a calculi-free outcome almost comparable to OS [8]. Its reported advantages over OS include lower morbidity, shorter operative time, shorted length of admission and earlier resumption of routine activity [9].

However, Zhang et al. [3] preferred OS over PCNL-based combination therapy for his cohort of complex SC. OS had better calculi-free status for cases having multiple calculi with calyceal extensions, as it permits simultaneous reconstruction of anatomical defects in the renal collecting system. Our patient had SC in the right kidney with numerous smaller calculi surrounding it and a solitary calculus in the left lower ureter. Because of the complexity of this case, simultaneous right-sided open extended pyelolithotomy and left-sided open ureterolithotomy were preferred. The procedure and post-operative recovery were uneventful. The patient was calculi free at 1-month follow-up.

CONCLUSION

PCNL is the treatment of choice for SC. However, large and complex SC associated with multiple nearby calculi are best treated with OS, especially in the presence of calculi on the contralateral side. This has the highest chance of achieving a calculi-free outcome through a single procedure. Thus, the principles of OS are still relevant in current urological practice and should be continued to be taught and practiced when required.

FUNDING

No sources of funding.

CONSENT

Informed Patient Consent was obtained.

GUARANTOR

Aruni Ghose (AG) was nominated as the guarantor.