-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

H Bouhdadi, J Rhissassi, H Wazaren, M Idrissa, C Benlafqih, R Sayah, M Laaroussi, Pulmonary and aortic endarteritis revealing a patent ductus arteriosus in an adult, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2022, Issue 1, January 2022, rjab565, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab565

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The ductus arteriosus, an essential fetal structure, normally closes spontaneously soon after birth. Its persistence into late adulthood is considered to be rare; infective endarteritis (IE) complicating a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is an even rarer event. The clinical picture of an infected PDA could be subtle, and the diagnosis is frequently delayed. We present the case of a young woman who presented with prolonged fever for whom we made the diagnosis of a PDA complicated by IE, with vegetations in both pulmonary and aortic walls with mycotic aneurysms of the descending aorta. She underwent surgery and the post-operative course was uneventful. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a PDA complicated with both pulmonary and aortic endarteritis.

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD), such as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), could be a predisposing factor of infective endarteritis (IE).

Mycotic aneurysm is an aneurysm that occurs due to an infection of the arterial wall. These are uncommon lesions, with a great potential for hemorrhage or sepsis. Since infectious aneurysm of the aorta has a tendency to expand rapidly in size and rupture, early diagnosis is very important.

We present the case of a 23-year-old woman, in whom the diagnosis of PDA complicated by endarteritis of both pulmonary artery and descending aorta was diagnosed, complicated by mycotic aneurysm of the descending aorta.

After 2 weeks of antibiotic treatment, the patient underwent surgical removal of the vegetation, closure of the mycotic aneurysm and section suture of the PDA.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 23-year-old female presented with 1-month history of intermittent high-grade fever, which was associated with lethargy and weight loss (2 kg in 3 weeks).

There was no history of chest pain, hemoptysis and dyspnea at rest. There was a history of recent dental intervention.

On examination, she was febrile and cachectic, with marked conjunctival pallor. There was a continuous murmur, with a thrill over the pulmonary area.

There were no other stigmas of infective endocarditis.

A chest X-ray was unremarkable.

On physical examination, temporal arteritis was 120/80, heart rate was 100 and body temperature was 38.5°C.

Auscultation revealed a continuous murmur in the left second intercostal space.

Laboratory workup showed the following: C-reactive protein: 100 mg/l, leukocytes: 12 000/mm3 and hemoglobin: 8.5 g/dl.

Two consecutive blood were positive for streptococcis viridans.

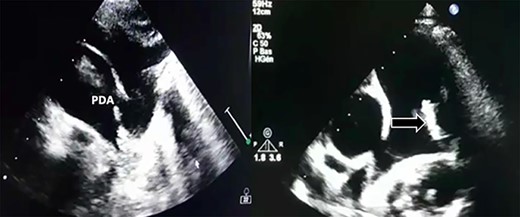

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a large PDA (10 mm) with left-to-right shunt and a fixed structure on the wall of the pulmonary artery, with erratic movement indicative of a vegetation (Fig. 1), and mobile vegetation attached to the wall of the descending aorta in the supra-sternal view (Fig. 2) and a left ventricle with conserved systolic function and 55-mm end-diastolic diameter.

Large PDA and a fixed structure on the wall of the pulmonary artery.

Supra-sternal view: vegetation attached to the wall of the descending aorta.

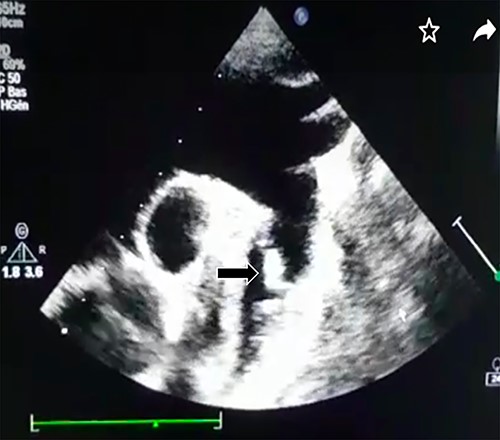

Computed tomography (CT) scan showed two mycotic pseudoaneurysms of the descending aorta (Fig. 3).

CT scan showing two mycotic pseudoaneurysms of the descending aorta.

Following 3 days of antibiotic treatment (ampicillin and gentamycin), she had symptomatic improvement and became afebrile.

A repeat echocardiography did show a disparition of the pulmonary vegetation, and a repeated CT scan showed no embolism to the pulmonary trunk.

Decision was made for surgical intervention.

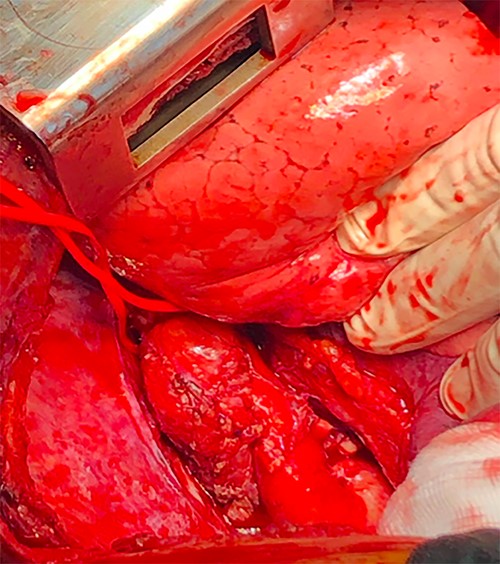

After establishment of a femoro-femoral partial bypass, the thorax was entered through the left fourth intercostal space. Two juxta- ductal aneurysmal formations with inflammatory adhesions were found (Fig. 4).

Preoperative image showing two juxta-ductal aneurysmal formations.

The proximal clamp was placed across the left subclavian artery and the distal clamp inferior to the false aneurysms site. The ductus arteriosus was initially clamped.

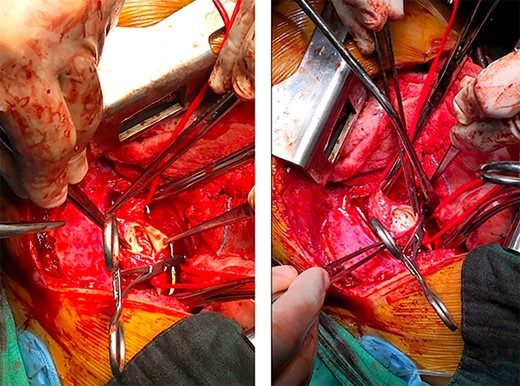

The descending aorta was opened, and we proceeded to debridement of the infected aorta from the vegetations and we decided to close the false aneurysms by direct sutures (Fig. 5).

Preoperative image after opening of the descending aorta; left: vegetations on the wall of the aorta; right: closure of the false aneurysms by direct sutures.

We then proceeded to a section suture of the PDA.

Post-operative course was uneventful.

Patient was discharged home after 2 weeks, and she was asymptomatic at 3-months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

PDA accounts for 5–10% of all CHD [1].

A PDA that persists beyond 1 month of age is estimated to occur in 0.3–0.8–4/1000 live births [2].

The size of a PDA can range from very large to <1 mm, and accordingly, the clinical findings associated with a PDA can vary considerably.

IE was the most common cause of death in patients with PDA prior to the introduction of antibiotic therapy and surgical closure of the defect, though nowadays, it is a rare complication. IE is especially unusual in asymptomatic patients, more so, when the PDA is silent on cardiac auscultation, with very few reports of this type of case to be found in the relevant literature [3].

An unrepaired PDA is a risk factor for IE, and when it occurs, vegetations usually occur on the pulmonary artery end of the ductus; embolic events are usually of the lung rather than the systemic circulation [4].

The proposed pathogenesis of IE associated with CHD involves complex interactions among the damaged valvular or mural endocardium, exposing the matrix proteins to thromboplastin and tissue factor, formation of a nonbacterial thrombotic endarteritis and eventual microbial adherence, colonization and replication. The turbulent blood flow through the aorta and pulmonary artery, which causes endothelial injury and subsequent seeding of pathogens onto the injured endothelium, is central to the proposed pathogenetic mechanisms for the development of vegetations particularly in patients with PDA [5].

The management of mycotic aneurysm is unclear. There are no strategies or recommendations regarding the timing of surgery (before or after antibiotics), aortic reconstruction (with or without material) and the duration of post-operative antibiotic therapy. Studies suggest that combined medical and surgical treatments decreases mortality [6].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we hereby report an unusual case of a young lady who had IE secondary to unknown PDA.

As the case reported shows, the risk for infection is present even in asymptomatic ducts and prophylactic closure of the PDA should be considered.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The patient gave oral consent for her personal medical report being submitted.

AVAILABILITY OF SUPPORTING DATA

The data set supporting the results of this article is in the manuscript and is included in the reference list.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

H.B. received the patient and conducted the patient interview. J.R., C.B., H.B. and M.I. performed the surgery. H.B. and H.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.