-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Masakatsu Hihara, Rina Hikiami, Toshihito Mitsui, Natsuko Kakudo, Atsuyuki Kuro, Kenji Kusumoto, Rare cases requiring emergency procedures while harvesting a free forearm flap: report of two cases, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2021, Issue 10, October 2021, rjab435, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjab435

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The free forearm flap is considered safe to harvest and is still extremely useful for reconstruction after head and neck tumor resection. We experienced two uncommon cases, in which an emergency procedure was required during reconstructive surgery after resection of head and neck cancer. Case 1 suffered persistent hand blood flow insufficiency long after the flap was placed in the oral cavity. Case 2 had an anomalous cutaneous vein of the forearm that was a drainage vein of the flap. For risk management during free flap surgery, preparing multiple venous transplant options in advance is fundamental.

INTRODUCTION

Perforator flaps, such as the anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap, are useful for performing reconstructive head and neck surgery, but the forearm flap, which is believed to be highly invasive at the donor site, is likely to remain in use due to its versatility, including its flexibility, as well as the regenerative capacity of the bones and nerves. While the application of this flap is recognized as being extremely safe, we encountered two cases wherein emergency procedures were required during surgery.

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

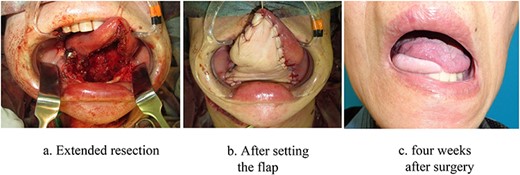

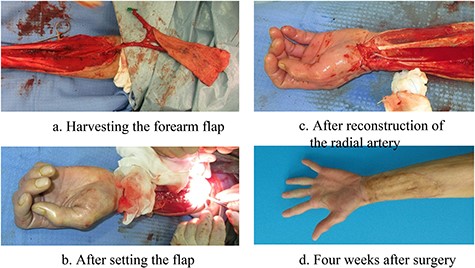

A 57-year-old woman underwent extended resection and reconstruction with a free forearm flap for oral cancer (cT2N0M0) (Fig. 1a-c). She had a wrist cut mark on the left wrist joint, but no impaired blood flow to the hand was observed in the preoperative modified Allen’s test. Just after harvesting the forearm flap as usual, however, blood flow disorder was observed in the entire hand (Fig. 2a). No special treatment was performed because it was assumed that spasm of the ulnar artery system had occurred. However, 2 h after the flap had been harvested, even after oral reconstruction, the blood flow disorder in the hand persisted (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the left great saphenous vein was grafted to the radial artery defect to reconstruct the radial artery system, improving the blood flow in the hand (Fig. 2c). Seven months after the surgery, the flap was engrafted, and there was no impaired blood flow to the hands (Fig. 2d).

Intraoral image of Case 1. (a) Extended resection. (b) After setting the flap. (c) four weeks after surgery.

Left forearm image of Case 1. (a) Harvesting a forearm flap. (b) After setting the flap. (c) After reconstruction of the radial artery. (d) Four weeks after surgery.

Case 2

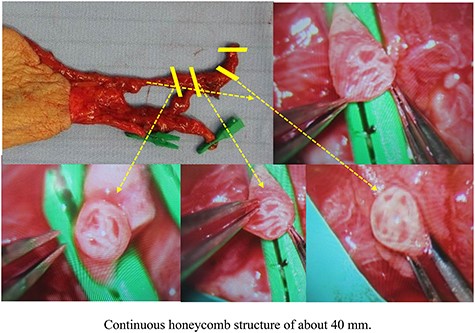

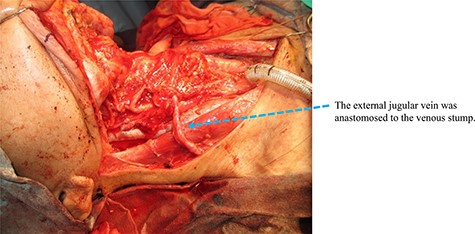

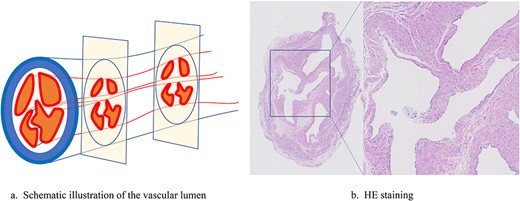

A 71-year-old woman was scheduled for reconstruction with a forearm flap for a partial pharyngeal defect after resection of laryngeal cancer (T3N2cM0). The forearm flap was harvested as usual, but the vascular lumen cross section of the forearm cutaneous vein, which is the main drainage vein, showed a honeycomb structure that unexpectedly continued for about 40 mm without interruption (Fig. 3). As end-to-side anastomosis to the internal jugular vein was considered inappropriate, the portion of the vein with inadequate drainage was cut out along a length of about 50 mm to the site where the normal vascular lumen appeared. The distal end of the external jugular vein was then anastomosed to the venous stump, and a very fine accompanying radial artery vein was additionally anastomosed (Fig. 4).

Image of the left forearm flap harvested in Case 2. Continuous honeycomb structure of about 40 mm.

Image of the right neck recipient area of Case 2. The external jugular vein was anastomosed to the venous stump.

DISCUSSION

Forearm flaps are still frequently used in reconstruction after head and neck tumor resection. The ugly shape of the donor site and need to sacrifice the radial artery have remained severe clinical problems, but its usefulness remains extremely high due to its high adaptation ability for complex defects and the suppleness of the flap.

We experienced two cases in which hand blood flow insufficiency occurred while harvesting a forearm flap, and the drainage vein of the flap collapsed over the entire length, resulting in the need for an emergency response. There have been several reports of hand blood flow disorders occurring while harvesting a forearm flap, as in Case 1. Acute cases include similar cases of hand blood flow disorder in flap surgery [1] and cases of hand acute ischemia during coronary artery graft harvesting for coronary artery reconstruction [2]. In these cases, vascular spasm is thought to occur in addition to peripheral angiopathy, such as hypertension and diabetes. Chronic cases include cases with finger necrosis occurring 1 year after the flap surgery [3]. Due to the risk of developing finger ischemia in the future, perhaps we should always utilize a vascular graft to repair a radial artery defect in order to sufficiently maintain the peripheral circulation [4].

There have been no reports of forearm flap harvesting cases with vascular malformations of the forearm as in Case 2. The pathological findings of the cutaneous veins in this case showed a structure in which the venous valve was maintained, so the possibility of multiple blood vessels being integrated was ruled out. Furthermore, due to the continuity of the valve structure and the lack of arterial three-layer findings, it might have been a case of venous malformation rather than arteriovenous malformation (Fig. 5a and b). Since venous malformation of the forearm is not rare [5, 6], preparing multiple venous transplant options in advance is fundamental for risk management during free flap surgery. In reconstruction procedures using free flaps in the head and neck area, we consistently prepare to anastomose two veins, the accompanying vein system and the cutaneous vein system when possible.

Vascular lumen of the drainage vein in Case 2. (a) Schematic illustration of the vascular lumen. (b) HE staining.

CONCLUSIONS

We experienced two uncommon cases related to blood flow insufficiency surrounding the harvesting of forearm flaps, resulting in emergency situations. It is important to prepare multiple options for addressing circulation disorders in advance when harvesting a free flap for head and neck reconstruction.

Consent

The patients in the present study gave their informed consent for the publication of their cases details and clinical photographs.

FUNDING

No funding support was obtained for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with the present study.