-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul Traynor, Weronika Stupalkowska, Tahira Mohamed, Edmund Godfrey, John M H Bennett, Stavros Gourgiotis, Fishbone perforation of the small bowel mimicking internal herniation and obstruction in a patient with previous gastric bypass surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 9, September 2020, rjaa369, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa369

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Intestinal perforation following the ingestion of fishbone is unusual and rarely diagnosed preoperatively, as clinical and radiological findings are non-specific. We report a case of a female patient post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) for obesity, who presented with severe abdominal pain and guarding in left iliac fossa. Computed tomography (CT) suggested internal herniation with compromised vascular supply to the bowel. Exploratory laparotomy identified a perforation site in the blind loop of the RYGBP due to a protruding fishbone. After extraction, primary suture repair was performed. In retrospect, the fishbone was identified on CT but misinterpreted as suture line at the enteroenterostomy site. This case emphasizes that although rare, the ingestion of fishbone can lead to severe complications and should therefore be included in the differential for an acute abdomen. On CT, it should be noted that fishbone may simulate suture line within the bowel if the patient has history of previous surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Foreign body (FB) ingestion is a common presentation in clinical practice. The majority will pass without complications [1]; however, sometimes they can result in perforation, thus requiring surgical intervention.

We report a case of fishbone perforation in a patient with previous Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) for obesity. The preoperative imaging misinterpreted the fishbone as suture line at the enteroenterostomy site and suggested internal hernia as a working diagnosis. The latter is a well-recognized complication in patients post RYGBP [2, 3]. It can be associated with significant morbidity, in particular bowel ischaemia, therefore prompt operative management is of paramount significance [2]. In our case, even though the preoperative diagnosis was inaccurate, the clinical and radiological findings were sufficient to make the correct decision for operative management of the patient.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old lady presented with severe pain in left iliac fossa (LIF), diarrhoea and vomiting for 2 days. Her past medical history included hypothyroidism and RYGBP for obesity over 10 years ago.

On examination, she demonstrated localized peritonism in LIF. Her observations were normal, and blood results showed white cell count of 16.5 (3.9 − 10×109/L) and C-reactive protein of 17.9 (0–5 mg/L) with the lactate of 1.0 (0.6–1.4 mmol/L).

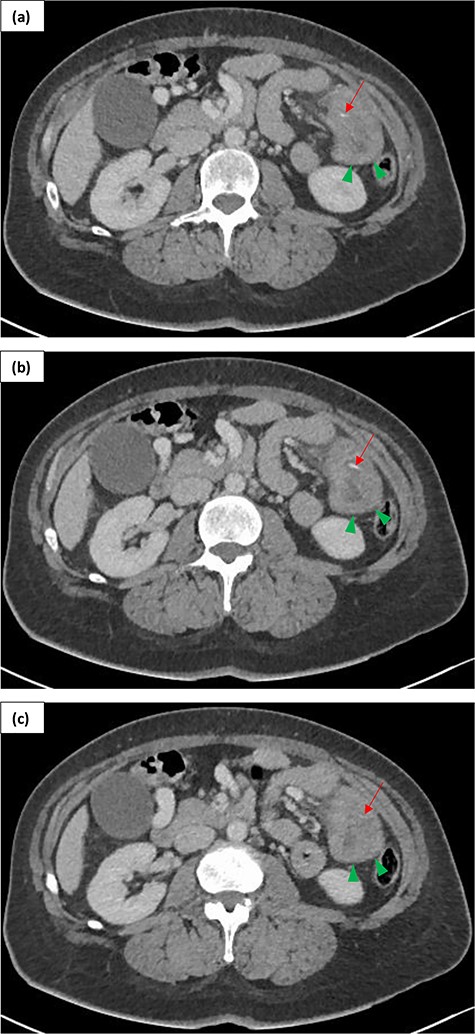

Admission computed tomography (CT) demonstrated thickened bowel loops in the left flank, related to the enteroenterostomy (Fig. 1). There was no mesenteric swirl, nevertheless, bowel thickening, venous compression and mesenteric oedema, in context of previous RYGBP, were concerning for bowel compromise secondary to internal herniation. It was felt that the probability of internal hernia in context of previous RYGBP, patient’s age and lack of significant past medical history was much higher than bowel ischaemia due to another reason. Linear high attenuation (representing the fishbone) was noted but presumed to be suture line at the enteroenterostomy (Fig. 1).

Contrast enhanced (portal phase) CT of a 54-year-old female presenting with LIF peritonism in context of previous RYGBP over 10 years ago. Serial images in axial plane (a, b, c) demonstrate thickened small bowel loops in the left flank (green arrowheads) and a fishbone as a linear hyper density (red arrow).

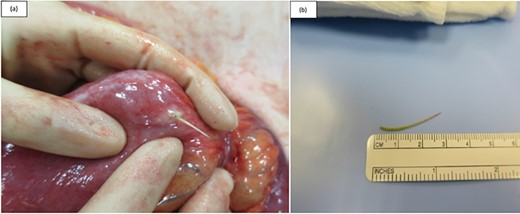

Because of high suspicion for bowel ischaemia, the surgeon decided to proceed to laparotomy rather than laparoscopy, which is performed more commonly in cases of suspected internal herniation [2, 3]. Intraoperatively, perforation was identified ~2 cm from the distal end of the RYGBP blind loop. This was due to a fishbone protruding from the lumen (Fig. 2). There was a localized fibrinous reaction but no abscess. A non-obstructing band-adhesion at the enteroenterostomy site was divided with diathermy. Both limbs of the RYGBP and the rest of the bowel to the level of terminal ileum were examined with no evidence of internal hernia or bowel ischaemia. Following extraction of the fishbone, puncture hole was repaired primarily with interrupted polydioxanone sutures.

Intraoperative photographs taken during exploratory laparotomy of a 54-year-old female presenting with LIF peritonism. (a) A fishbone was identified protruding from the lumen of the blind end loop of the Roux-en-Y anastomosis (patient had history of previous RYGBP for obesity). (b) Fishbone after its extraction.

The patient was discharged on postoperative Day 6 but subsequently re-presented 7 days later with portal vein thrombosis (PVT). Interestingly, although the PVT was not evident on the preoperative scan, it was noted that the appearance of superior mesenteric vein (SMV) was abnormal—it was hypothesized that the patient might have suffered SMV thrombosis in the past with resulting multiple collaterals draining into the SMV and splenic vein confluence and the gastrocolic trunk. The patient was commenced on anticoagulation and her thrombophilia screen was negative.

DISCUSSION

Around 75% of ingested FB will pass spontaneously without complications; however, up to 25% will require either endoscopic or surgical intervention [1, 4]. A total of 1% will perforate the gastrointestinal tract [1, 4], most commonly in areas of physiological narrowing or angulation such as the cricopharyngeus, lower oesophagus or the ileocaecal and rectosigmoid junctions [5, 6]. Anastomoses and areas with adhesions have also been implicated [6] and indeed in our case the reconfiguration of the bowel post RYGBP might have been a contributing factor.

Often fishbone perforations masquerade as other causes of surgical abdomen and misdiagnosis is the norm rather than exception. In our case, the working diagnosis was that of an internal hernia given previous history of RYGBP. It is reported that up to 9% of patients post RYGBP will develop this complication [3], hence it should always be considered as a differential diagnosis for acute abdomen in this patient group.

In our case, the surgeon decided to proceed straight to exploratory laparotomy rather than diagnostic laparoscopy because the suspicion for bowel ischaemia was high. We do acknowledge, however, that in cases of suspected internal hernias, most patients are successfully managed laparoscopically [2, 3]. Regardless of operative approach, the patient should be taken to theatre without delays, due to associated risk of bowel ischaemia and death.

The largest risk factor for unintentional fishbone ingestion is the use of dentures, due to associated impairment in palatal sensory function. Other risk factors include extremes of age, cognitive impairment, alcoholism and regional cuisine habits of preparing whole fish with bones [6, 7].

The most accurate imaging modality for visualizing fishbones in the gastrointestinal tract is a contrast-enhanced CT. Some authors report up to 100% sensitivity on retrospective review of their images [7]. Fishbones appear as high-density linear objects surrounded by inflammatory changes of the adjacent bowel and can be visualized on thin slice images of no more than 2 mm [8, 9]. Multiplanar reconstructions can increase sensitivity further [8, 9]. Other features include localized pneumoperitoneum, abscess formation, fistulation into adjacent structures, localized luminal narrowing causing obstruction or even a free-floating bone within the peritoneal cavity [7, 9].

Even though most fishbones are visible on preoperative scans, they are often misinterpreted as other structures [7]. Similarly, in our case, the fishbone was thought to represent a suture line from previous surgery. Fortunately, there were enough clinical and radiological signs to precipitate laparotomy, which allowed safe management of the patient and the correct diagnosis to be made.

The intraoperative findings were fed back to the Radiologist—interestingly, it was felt that the degree of bowel wall thickening and venous engorgement seen on preoperative CT did not correspond to the intraoperative findings of healthy bowel, raising a suspicion of an intermittent internal hernia, which perhaps self-reduced before surgical exploration.

In conclusion, intestinal perforation secondary to fishbone ingestion remains a challenging diagnosis. On CT, the fishbone can often be misinterpreted for other structures, for example suture line. This case illustrates that in order to safely manage patients with acute abdominal pain, it is often more important to use clinical and radiological findings to decide whether surgical exploration is required, rather than to pinpoint the exact diagnosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.