-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Iroukora Kassegne, Kokou Kouliwa Kanassoua, Tamegnon Dossouvi, Yawod Efoe-Ga Amouzou, Aboza Sakiye, Komlan Adabra, Fousseni Alassani, Ayi Kossigan Amavi, Boyodi Tchangai, Tabana Essohanam Mouzou, Ekoue David Joseph Dosseh, Duodenocolic fistula by nail ingestion in a child, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 8, August 2020, rjaa187, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa187

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Unintentional foreign body ingestion is common among children. Normally, these ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously. Only few of them may lead to complications such as fistula, which requires surgical intervention. We are reporting a case of accidental construction nail ingestion in a 3-year-old male child, for 30 days, without any symptoms. Diagnosis of duodenocolic fistula by construction nail was made on clinical examination and abdominal radiography features. He underwent surgical intervention, with nail removal, dudenal and colic primary closure. The follow-up was uneventful. We recommend emergently retrieval of sharp-pointed and long-ingested foreign bodies like a construction nail. Conservative outpatient management by clinical observation is not appropriate for this kind of foreign bodies. It may lead to complications such as perforation and fistula.

INTRODUCTION

Ingestion of foreign bodies (FBs) is encountered commonly in the pediatric population, with a peak incidence in children aged 6 months–3 years [1]. Most ingested FB (80–90%) pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously; only <1% cause significant complications, such as perforations, which require surgical intervention [2].

Recently, we experienced a male child, who underwent laparotomy for accidental FB ingestion. This case report presents a rare case of a duodenocolic fistula by construction nail ingestion in a child. To our knowledge, such a case of ingested nail causing duodenocolic fistula has not been reported previously.

CASE REPORT

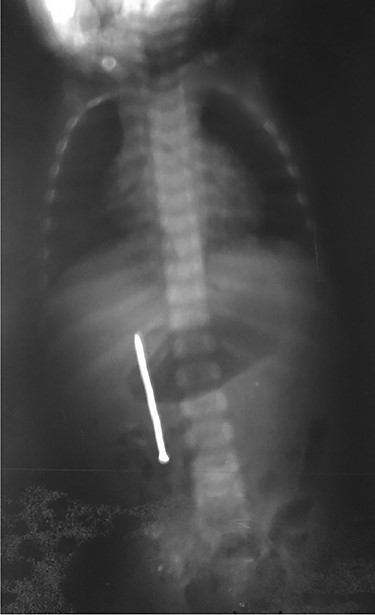

A 3-year-old male child was admitted in surgery department, with history of accidental ingestion of construction nail for 30 days, without any symptoms. Parents consulted in a peripheral hospital and plain abdominal radiography showed a nail projected in right-edge upon the lumbar spine (Fig. 1). Clinical observation was advised. The nail did not pass spontaneously and the child remained asymptomatic. Parents decided to consult again, but in our institution (surgery department). The child did not experience fever nor digestive symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, blood or color changes in stool). He had no prior history of FB ingestion.

Abdominal examination was normal. A repeat abdominal radiography was done. The nail’s position had not changed from the first X-ray site, with no free peritoneal air (Fig. 2).

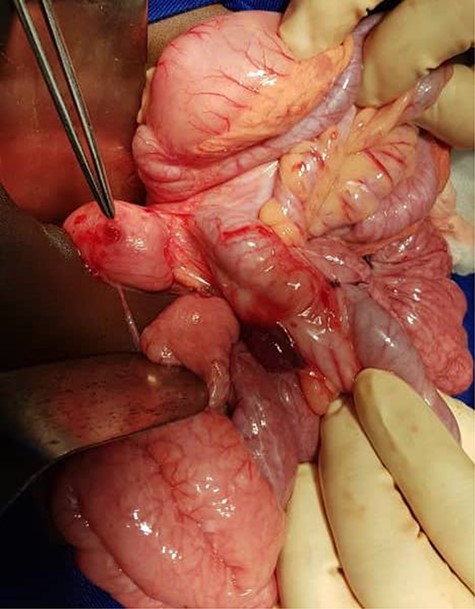

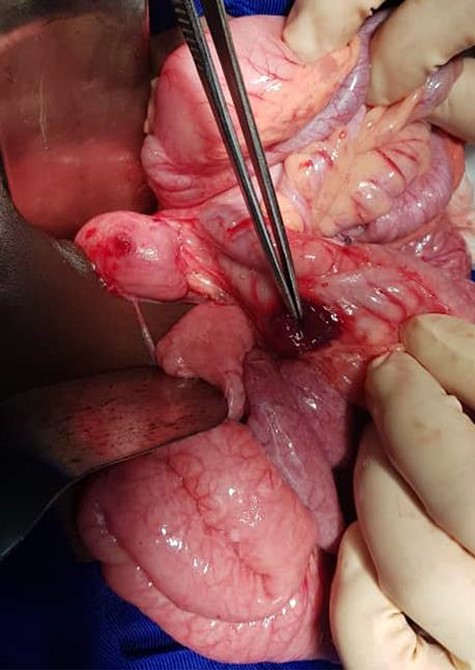

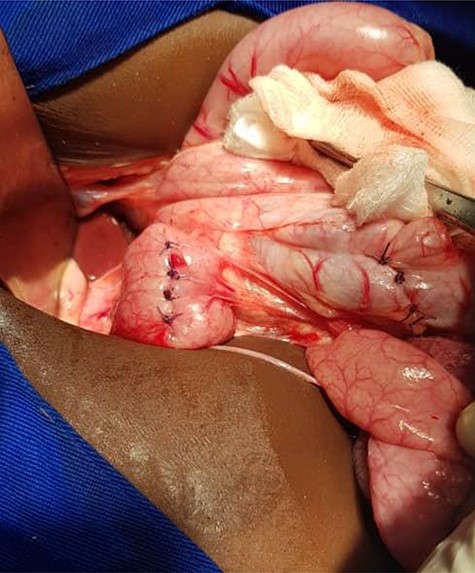

Urgent laparotomy exploration was planned. Intraoperatively, the nail was impacted and palpated through ascending colon wall. The nail was extracted through a minim colic incision centered on its head (Fig. 3), measuring ~6 cm. The ascending colon was mobilized, showing a second part of duodenum anterior wall (Fig. 4) and ascending colon posterior wall perforations (Fig. 5). There was neither peritonitis nor intraperitoneal free fluid. No spillage was noticed in the peritoneal cavity. Intraoperative diagnosis of duodenocolic fistula by nail ingestion was made. All perforations were repaired primarily (by multiple simple interrupted sutures) and drain was placed near repairs (Fig. 6). The follow-up was uneventful. The child was discharged on day 8.

DISCUSSION

Ingested FB complications (impaction, obstruction, perforation or fistula) often occur at areas of physiological narrowing or angulation (duodenal sweep). The rigid nature of the duodenum as well as its sharp angulations makes it a common site for their entrapment, lead to impaction and perforation. In addition, the gastrointestinal tract perforation may involve adjacent structures [3, 4]. Ascending colon involvement, leading to duodenocolic fistula, has not been reported previously.

In our case, according to the nail’s position on abdominal radiography, perforations were probably due to duodenal wall extension and progressive erosion of the nail’s head through the duodenal wall [3–5]. Our patient did not present signs of peritonitis neither free peritoneal air (pneumoperitoneum) because the site of duodenal perforation was covered by adjacent loops of ascending colon. This avoids the passage of intraluminal air into the peritoneal cavity.

Plain radiography plays the main role both in the diagnosis and the choice of operative interventional moment—either by pinpointing the radio-opaque image, or by showing certain FB characteristics, or by noting images suggesting complications (absent in our case), or even by projecting the FB in the same place over a period of time, an aspect inductive of fistula. In our case, right-edge superposition of the FB image upon the lumbar spine is characteristic of FB positioning in the second part of duodenum [5, 6]. Its persistence in the same place (the second part of the duodenum as in our case) suggests the presence of a duodenal fistula or perforation, which requires surgical intervention [7].

Endoscopy is the best diagnostic and safest therapeutic approach in the management of FB in the upper gastrointestinal tract. It is recommended urgent (within 24 hours) retrieval of duodenal sharp-pointed FB, according to the high risk of complications (15–35%) [3]. Surgical intervention should only be taken in case of signs of peritonitis, failure of endoscopy or the presence of FB inside gut for >3 days [1, 3, 8]. In our case, despite no signs of complications, urgent laparotomy was planned for many reasons: endoscopy was unavailable; the position of the nail did not change even after 1 month, suggesting fistula; and the FB characteristics (sharp-pointed, >5 cm). The diameter (small) and the edges (smooth) of the perforations, the absence of peritoneal contamination and inflammation, prompted us to perform colic and duodenal perforations primary closure.

In summary, efforts should be made to remove emergently sharp-pointed and long-ingested FB like a construction nail. Conservative outpatient management by means of clinical observation is not appropriate for this kind of FBs. It may lead to complications such as perforation and fistula.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.