-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yves Alain Notue, Ulrich Igor Mbessoh, Tim Fabrice Tientcheu, Boniface Moifo, Alain Chichom Mefire, Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to peptic ulcer disease, previously misdiagnosed as idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 16-year-old girl: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 7, July 2020, rjaa232, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa232

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric outlet obstruction encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions characterized by complete or incomplete obstruction of the distal stomach, which interrupts gastric emptying and prevents the passage of gastric contents beyond the proximal duodenum. Idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the most common cause with an incidence of 1.5–3 per 1000 live births. However, it is excluded; other causes in children such as peptic ulcer disease are relatively rare. We report a case of an acquired gastric outlet obstruction due to peptic ulcer disease, previously misdiagnosed as idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 16-year-old girl. Beyond the rarity of this clinical event, this case highlights the challenges of the aetiological diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction with subsequent therapeutic issues, and is the first documented case in Cameroon.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric outlet obstruction encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions characterized by complete or incomplete obstruction of the distal stomach, pylorus or proximal duodenum, which interrupts gastric emptying and prevents the passage of gastric contents beyond the proximal duodenum [1–4]. It is the clinical and pathophysiological consequence of any disease process that produces a mechanical impediment to gastric emptying [2, 5, 6]. The incidence of paediatric gastric outlet obstruction is ~2–5 per 1000 [4]. Among them, idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the commonest cause with an incidence of up to 1.5–3 per 1000 live births [7]. When idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is excluded, the other causes of gastric outlet obstruction in children like peptic ulcer disease are relatively rare [1, 6, 8]. We report a case of an acquired gastric outlet obstruction due to peptic ulcer disease, previously misdiagnosed as idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a 16-year-old girl. Beyond the rarity of this clinical event in paediatric population, this case highlights the challenges of the aetiological diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction with subsequent therapeutic issues, and to our knowledge it is the first documented case in Cameroon.

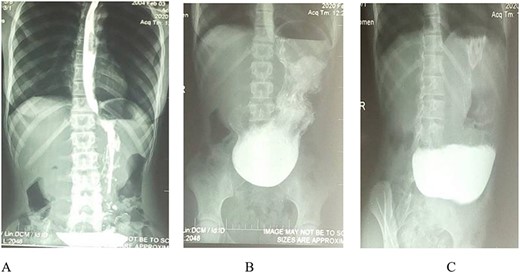

Barium meal: (A and B) Erect anteroposterior view show prolongation of stomach to suprapubic region. B and C (oblique view): Show gastric distension, no passage of contrast medium into the duodenum and delayed gastric emptying (C).

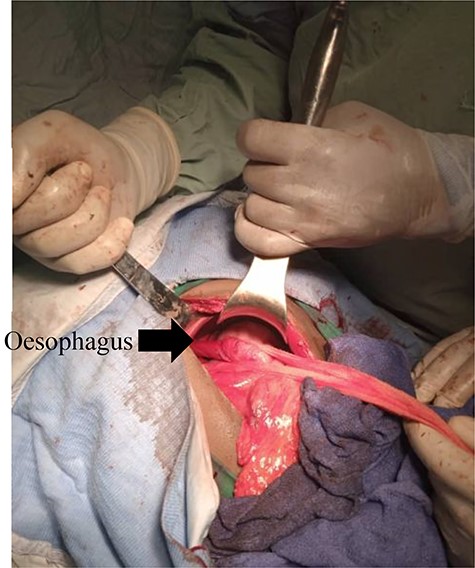

Draschsted’s bilateral troncular vagotomy completed by Toupet’s posterior hemivalve.

CASE REPORT

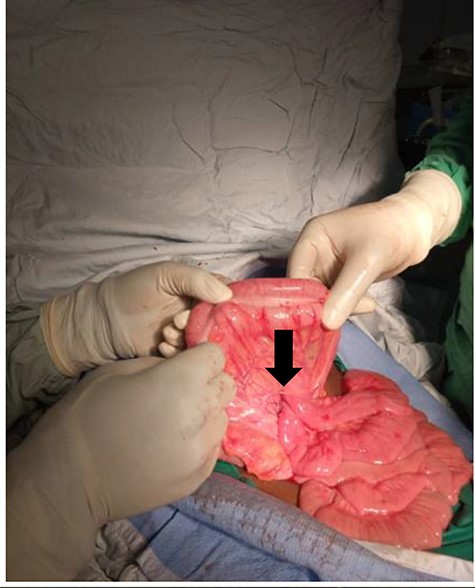

A 16-year-old girl was admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain, vomiting and moderate growth retardation. She was healthy and well-nourished until 12 years of age when she began having abdominal pain and projectile non-bilious vomiting, especially after heavy meals. During the two subsequent years, she gradually lost weight, with increasing frequency of vomiting after both heavy and light meals, even after drinking water, and now associated with constipation. She consulted a physician and a diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis was made based on ultrasonography findings. She was then operated for hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Six months later, she started experiencing the same symptoms with a similar pattern (gradual increase in frequency and intensity). She had a history of peptic ulcer disease since 11 years of age, but no history of caustic ingestion, malignancy, gastric polyps or non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug medication. There was a positive family history of peptic ulcer disease, but no family history of parental consanguinity. Physical examination revealed an afebrile and haemodynamically stable patient with anthropometric parameters between the 10th and the 5th percentiles. Her abdomen was not distended but showed an epigastric tenderness, and normal bowel sounds were heard on auscultation. However, visible gastric peristalsis was observed during bouts of vomiting. She was positive at the Helicobacter pylori serology and routine urine tests were normal, as well as serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests. A barium meal showed marked gastric distension, with delayed gastric emptying and no contrast medium in the duodenum (Fig. 1). These findings were consistent with gastric outlet obstruction but of unknown aetiology. An exploratory laparotomy was done that showed a grossly dilated stomach, scarred pylorus and enlarged lymph nodes along the lesser curvature of the stomach. An omega transmesocolic gastrojejunal anastomosis (Fig. 2), Draschsted’s bilateral troncular vagotomy and Toupet’s posterior hemivalve were performed (Fig. 3). Histopathological examination of the enlarged lymph nodes showed non-specific chronic lymphadenitis without malignant cells. Post-operative evolution was favourable; she gained 6 kg the first month after operation. She was symptom free at follow-up, 3 months after laparotomy.

DISCUSSION

In paediatric groups, gastric outlet obstruction is most often the result of idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis [4]. Although the exact incidence of gastric outlet obstruction in the older child is not well-established, some reports estimate at <5% incidence in patients with peptic ulcer disease [2, 9], which suggests the rarity of this reported case. According to the literature, males are more commonly affected than females, which may vary from 3:1 to 4:1 ratio [1, 10]; but in this case, the patient was a female. In the study by Feng et al. [10] on rare causes of gastric outlet obstruction in children,, the patients’ ages ranged from 45 days to 13 years, showing the substantial variability of age of onset of the disease in paediatric groups, which can reach 16 years old as in this case.

The main aetiologies of gastric outlet obstruction are well-described in books and published articles [2, 4, 7, 9, 10]. Many classifications exist, but they are commonly classified in congenital and acquired causes [2, 4, 7, 9, 10]. So, although, idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in children [4], acquired causes such as peptic ulcer disease, caustic ingestion, tumour, chronic granulomatous disease and eosinophilic gastroenteritis [7] have to be systematically investigated and excluded in order to decrease misdiagnosis rate. To differentiate gastric outlet obstruction from idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis origin or peptic ulcer disease origin is a major diagnostic challenge to physicians practising in resource-limited countries [2] with serious therapeutic implications as shown in the case report. So, peptic ulcer disease origin should be considered as the likeliest cause when the patient has a family and personal past history of peptic ulcer disease and is positive on H. pylori serology [6].

Concerning the management patterns, according to many reports children with gastric outlet obstruction secondary to peptic ulcer could be successfully treated with vagotomy combined with pyloroplasty, antrectomy, or gastrojejunostomy [2, 7, 9, 10]. In this case, an omega transmesocolic gastrojejunostomy, Draschsted’s bilateral troncular vagotomy and Toupet’s posterior hemivalve were performed. Some authors reported that the introduction of endoscopic balloon dilation has simplified the treatment of benign gastric outlet obstruction due to peptic ulcer disease and is associated with favourable long-term outcome. Moreover, it is now considered to be the first-line treatment [3, 8].

In conclusion, although idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is the main cause in this population, physicians have to be aware of others potential underlying acquired causal diseases in order to decrease occurrence of misdiagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the nurse staff of the Mbouo Protestant Hospital’s Surgery Department for their contribution in the management of the patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.