-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Moises Enghelberg, K V Chalam, Ultra wide field angiography documented peripheral retinal eovascularization as cause of vitreous hemorrhage after scleral buckle surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 6, June 2020, rjaa142, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa142

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We describe an unusual case of ultra wide fluorescein angiography (UWFA) documented peripheral retinal neovascularization (NVE) with delayed vitreous hemorrhage after placement of an encircling scleral buckle (a common procedure for repair of retinal detachment). Anterior segment ischemia is a rare complication after scleral buckle surgery for the treatment of retinal detachment and results from altered choroidal flow through the impingement of the anterior and long posterior ciliary arteries. UWFA performed for the evaluation of vitreous hemorrhage confirmed ischemia anterior to the scleral buckle and consequential NVE. This case represents the utility of UWFA in evaluating and managing this exceptionally rare complication associated with a common procedure in the field of vitreoretinal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Exoplants through scleral indentation approximate the detached retina to the sclera and accelerate adhesion between retinal pigmented epithelium and retina [1]. This successful strategy is commonly employed in the management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments (RRDs) and is a staple of vitreoretinal surgery.

Common complication of encircling buckles involves patient discomfort, extrusion of the exoplant, exotropia and anterior segment changes [2, 5]. Anterior segment ischemia is an uncommon complication and is rarely associated with retinal neovascularization (NVE).

We describe a rare case of delayed loss of vision from vitreous hemorrhage secondary to extensive retinal capillary non-perfusion (CNP) and NVE of peripheral retina after placement of scleral buckle for RRD. Ultra wide field fluorescein angiography [UWFA (a recent advance in the field of retinal imaging)] revealed a large area of CNP with associated NVE as the reason for the vitreous hemorrhage.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old male, with a past ocular history of repair of retinal detachment of the right eye (pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser 360°, as a well as cryopexy, and scleral buckle placement 3 years earlier) presented with sudden onset of decrease of vision of 2-day duration.

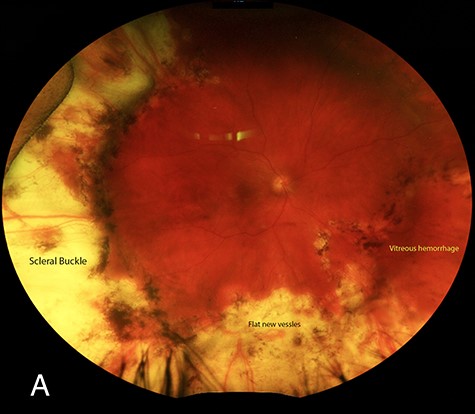

Patient’s best corrected visual acuity was 20/200 OD and 20/20 OS. Intraocular pressure was 9 mmHg, OD and 10 mmHg, OS. Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was normal with well positioned posterior chamber intra ocular lenses. Fundus examination revealed hazy media, vitreous hemorrhage, scleral buckle and peripheral neovasculization (Fig. 1). Examinations of the left fundus revealed mild drusen consistent with early age-related macular degeneration (Fig. 2).

Fundus photograph of the right eye. ScleraI indentation is present secondary to the buckling element. An area of retinal NVE is present close to 6 o’clock.

Fundus photograph of the left eye. Laser prophylactic photocoagulation for retinal holes.

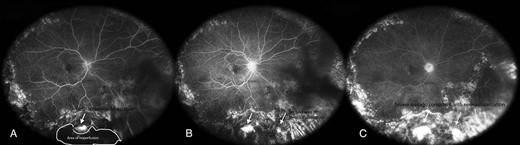

UWFA demonstrated a large area of hyperfluorescense consistent with NVE in the far periphery at 5:30 o’clock. A large area of CNP was noted anterior to the NVE (Fig. 3A). A second discrete area of NVE at 5 o’clock was noted in mid-phase (Fig. 3B). Leakage in the late phase of the angiogram at the aforementioned area revealed diffuse leakage consistent with NVE. The second area at 5 o’clock also exhibited similar leakage (Fig. 3C). Staining in the periphery secondary to chorioretinal scarring was also noted.

(A) Area of NVE with hyper fluorescence with large area of capillary non-perfusion noted anterior to the retinal NVE. (B) A second discrete area at 5 o’clock that exhibits hyper fluorescence consistent with retinal NVE (red arrow). (C) At 4:44, the aforementioned area has diffuse borders which are consistent with leakage and suspicious for NVE (white arrow). The second area at 5 o’clock also presents increase in continued late leakage with hyper fluorescence consistent with leakage (red arrow).

UWFA was performed 48 hours after initial presentation (after bed rest and appropriate head positioning to facilitate UWFA). Vitreous hemorrhage settled nasally and allowed the visualization of CNP. BCVA improved to 20/70. Patient declined surgical intervention.

Four months after initial presentation, visual acuity improved to 20/40. Vitreous hemorrhage improved.

DISCUSSION

Encircling elements have a success rate of approximately 84.7% [3]. Phakic patient tend to do have a better outcome, while anatomic success in pseudophakes is approximately 73.9%. Common complications associated with scleral buckling are refractive change, intrusion or extrusion, infection, globe ischemia and choroidal detachments [4]. In patients, after encircling buckling procedures, the buckling elements were loose in 59% of their patients [5]. The high re-operation rate is due to recurrent retinal detachments, extrusion of the exoplant and anterior segment changes [2, 5]. Despite the frequent use of scleral buckles in vitreoretinal surgery and their well-studied effect on choroidal and retinal blood flow, it seldom results in retinal NVE.

In a report by Cohen et al., a patient developed anterior segment ischemia and retinal NVE anterior to the encircling buckle. The buckle had to be removed and repositioned. The patient did well after multiple procedures including an anterior vitrectomy and further argon laser placement accompanied by cryopexy [6]. However, the reason for peripheral NVE was not clear.

Changes in circulation after scleral buckle placement are likely, as buckle indents retina through mechanical compression of underlying structures. Ogasawara et al. described the changes in circulation after scleral buckle with the aid of a bidirectional Doppler technique and measured the perfusion of the major temporal retinal arteries in eyes with scleral buckles and compared them to the surgically naive contralateral eye. The retinal arterial flow rates were 50% lower than the flow rates measured in corresponding retinal arteries in fellow eyes. Differences in vessel diameter and differences in blood speed were also assessed. On average, retinal vessel diameters were 7% smaller in treated than in fellow eyes [7].

Sugawara et al. showed that segmental scleral buckling procedure with encircling elements decreased choroidal blood flow in the foveal region in patients without macular involvement [8]. On the other hand, using the laser speckle method, Nagahara et al. reported that the segmental scleral buckling procedure with encircling elements decreased tissue blood velocity in the choroid and retina on the buckled side but caused no marked change in tissue circulation in other areas of the fundus region or optic nerve head [9]. Interestingly, Yoshida et al. demonstrated that (with the aid of a cerebral vascular monitor with an amplified signal) scleral buckling affects the ocular pulse measurements and may decrease ocular blood flow because of decreased ophthalmic artery pressure [10]. However, alteration induced by scleral buckle in both choroidal and retinal blood flow is well tolerated by the great majority of patients. An average decrease in blood velocity was estimated to be 45% with 7% decrease in retinal vascular diameter [10]. Alterations caused by the peripheral retinal NVE in conjunction with the vascular attenuation seen in some patients with accompanying vascular disease could produce an even greater threat to retinal circulation.

In our patient, on dilated fundoscopy, a vitreous hemorrhage was the cause of sudden decrease in vision, and the differential diagnosis of anterior segment ischemia secondary to the scleral buckle was entertained as well trochar site NVE. UWFA revealed a large area of CNP anterior to scleral buckle. In addition, two areas of florid NVE were noted. We believe scleral buckle induced alteration in microcirculation possibly stimulated vascular endothelial growth factor release and induced NVE. UWFA confirmed the presence of both CNP and NVE adjacent to the area of CNP.

In summary, we describe a rare case of UWFA documented vitreous hemorrhage with NVE after scleral buckle placement secondary to altered retinal circulation including capillary non-perfusion.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

None.

Footnotes

#Presented as paper at Annual meeting of American Society of Retina Specialists, Chicago, 2019