-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia Porter, Jacob Eisdorfer, Crystal Yi, Cecilia Nguyen, Multifocal abdominal endometriosis, a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 6, June 2020, rjaa120, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa120

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Multifocal endometriosis found outside of the pelvis is very rare. We present here a case of endometriosis found in the pelvis, appendix and umbilicus. A 52-year-old female had a previous umbilical hernia repair, and years later started to develop a recurrent umbilical mass. After a full work-up, it was decided the patient have a diagnostic laparoscopy with wide local excision of umbilical mass to rule out any underlying malignancy. Findings during the procedure included an umbilical mass, dilated appendix and ovoid mass abutting the appendix. Pathology of the umbilical mass was found to be consistent with endometriosis. Umbilical and pelvic endometriosis is a rare condition. Options for diagnosis prior to surgical interventions are limited in endometriosis. In this case, ruling out underlying malignancy took priority, and the mass was removed and she will have less chance of recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is defined as endometrial tissue outside of the uterine cavity [1]. Endometriosis to be found at the umbilicus is a rare occurrence, especially in a woman with no prior history of endometriosis elsewhere. The incidence of women with endometriosis is hard to quantify because many women may remain asymptomatic. The overall incidence is 0.14% annually in women from ages 15–50 [2]. Incidence in those reporting symptoms specific to endometriosis is much higher. In those reporting pelvic pain is ~50% [3], and those reporting infertility is ~20–50% [4]. Endometriosis can develop anywhere within the pelvis or extrapelvic peritoneal surfaces, but the most common places are the pelvic peritoneum, cul-de-sac, fallopian tubes, uterosacral ligaments and the ovaries [1]. The appendix and the umbilicus are rare areas for endometriosis to be found. Of those with endometriosis, 2.8% have endometriosis located at the appendix and in 0.5–4% of the cases it is located at the umbilicus [5, 6]. The most common symptoms include pelvic pain, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea and infertility [1]. Those with umbilical endometriosis may present with cyclical umbilical pain around menstruation. The umbilicus may start to bleed during menstruation [7]. Appendiceal endometriosis can present in a variety of ways, but the most common is pain in the right lower quadrant [8]. Imaging is of little use in diagnosing endometriosis, and diagnostic laparoscopy remains the gold standard [9]. The treatment of endometrioses depends on the symptoms and severity. The mainstay of treatment for pain related to endometriosis is hormonal agent such as progestin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, antagonists, estrogens and androgens [10]. Surgical excision is a definitive treatment, but reoccurrence is certainly possible [10]. As discussed earlier, umbilical and appendiceal endometriosis are rare; the conglomeration of these three foci of endometriosis is even more rare. Herein we describe a case of a 52-year-old female with pelvic, appendiceal and umbilical endometriosis.

The umbilicus without erythema or induration, note the scare from previous umbilical hernia repair.

CASE DESCRIPTION

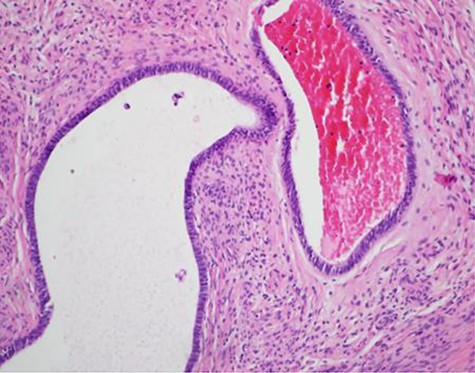

A 52-year-old female presented with complaints of increasing umbilical pain and swelling for a year. She described the pain as intermittent and daily. She denied any aggravating factors. There was no correlation with eating or movement, and she had no relief with Tylenol. Fourteen years ago, she had an umbilical hernia repair at an outside institution, per their documentation; this was done primarily, without mesh. She also had a colonoscopy and upper endoscopy a year prior, which was negative. Her past medical history was remarkable for uterine fibroids. On exam the abdomen was soft and non-distended; the umbilicus was tender to palpation, with no hernia defect palpable. There was no erythema or induration (Fig. 1). At this time the differential included a suture granuloma, benign or malignant mass. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis relieved no hernia but there was an umbilical mass present, a thickened appendiceal tip, abutting a large uterine fibroid (Fig. 2). Tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 and CA 125 were obtained and within normal limits. At this time it was decided that surgical intervention was warranted for increased concerns of malignancy, and a Sister Mary Joseph nodule could not be excluded. The patient was brought to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy. The umbilical mass was excised with a margin of grossly normal tissue (Fig. 3). There were noted to be dense fibrotic adhesions involving the appendix, cecum. The appendix was removed along with a 2-cm ovoid nodule and was sent to pathology along with the umbilical mass. The patient was discharged home the next day without any complications. The pathology revealed an umbilical mass consistent with endometriosis, a pelvic nodule consistent with leiomyoma and a focal area consistent with endometriosis (Fig. 4) She presented to clinic 2 weeks later with no pain or tenderness.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis is a common disorder among women of reproductive age. Endometriosis at the umbilicus is very rare. It was first described by Villar in 1886 and has been known as Villar’s nodule [7]. Only 0.5–4% of women are found to have endometriosis of the umbilicus [6]. This can be primary or secondary in nature. Primary umbilical endometriosis is thought to be caused by migration of endometrial cells to the umbilicus possibly through the lymphatics or the urachus or umbilical vessels, which are from embryonic remnants. Secondary umbilical endometriosis is caused by surgically induced trauma to the area displacing endometrial cells [6]. Women with umbilical endometriosis have commonly complained of increased pain with menstrual cycle or bleeding from the umbilical mass during their menstrual cycle. Diagnosis is challenging because many imaging studies have limited use; neither ultrasound, MRI nor CT is of great diagnostic value [9]. Surgical exploration is warranted for a definitive diagnosis and alleviation of symptoms. Endometriosis can at times be treated with hormones, but this is not a permanent fix [9].

Although this patient did have some of the findings of umbilical endometriosis, there are also many factors that alluded to other causes. The patient was postmenopausal. Most women presenting with endometriosis are between 18 and 45 [9]. She also denied cyclical pain, discharge or bleeding from the site. In the month leading up to her surgery, it was noted that there was increased erythema and pain from the mass. Although this patient fits the category of secondary umbilical endometriosis, because of her previous hernia repair, this created a list of far more common differential diagnoses, such as suture granuloma or recurrence of umbilical hernia. The CT scan obtained, revealed an umbilical mass, excluding possible hernia, but created a new possible diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph Nodule.

A Sister Mary Joseph Nodule is a term for an umbilical nodule that is from metastatic intra-abdominal or pelvic cancer [10]. The prognosis is usually grave, with a survival time on average of 10 months. The presentation of these nodules is similar to that of umbilical endometriosis. They are usually described as a small, firm mass. They have presented in a variety of colors including white, blue or red. They also may be ulcerated or fissured. The masses are usually painless, unless ulcerated [10].

The finding of appendiceal endometriosis was unexpected. Appendiceal endometriosis was first described in 1860 and has since been seen in cases ranging from asymptomatic, lower gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal perforation or obstruction [8]. The most common presenting symptom is pain in the right lower quadrant [8]. Our patient did not have any history or right lower quadrant pain; as stated earlier, her pain was located at the umbilicus. Preoperative diagnosis can be difficult, and the standard of treatment is laparoscopy with appendectomy, and the official diagnosis can be made by pathology, which was how our patient was diagnosed [8].

CONCLUSION

Umbilical and pelvic endometriosis is a very rare condition, especially in postmenopausal women. An option for diagnosis prior to surgical interention would have included fine need aspiration, fine needle aspiration, although being that our patient had a thickening of her appendix on CT scan and was symptomatic from umbilical pain, the decision was made for wide local excision of umbilicus, removing the pelvic mass and the appendix. Having done all this, we successfully removed the mass and she will have a lower chance of recurrence.