-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Daniel Page, Sujith Ratnayake, A rare case of emphysematous pancreatitis: managing a killer without the knife, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 6, June 2020, rjaa086, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa086

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Emphysematous pancreatitis (EP) is a rare and severe complication of acute pancreatitis carrying a high mortality with only a handful of case reports and small studies reporting these cases and their management. The presence of emphysematous pancreatitis is often indicative of infected pancreatic necrosis with the mainstay of treatment being pancreatic necrosectomy; however there are cases where it may be appropriate to have a trial of conservative management, and there is a small body of evidence to support this. This paper describes a case of an 87-year-old male with acute emphysematous pancreatitis successfully managed with conservative cares.

INTRODUCTION

Emphysematous pancreatitis (EP) is a rare, severe and life-threatening complication of acute pancreatitis that results in a mortality of >50% compared with the overall mortality of acute pancreatitis of 4% [1, 2].

EP is typically associated with co-morbid individuals with immune suppression, poorly controlled diabetes or chronic renal failure [1, 3]; also there are case reports of EP seen in patients with HIV caused by TB [4].

EP is often indicative of infected pancreatic necrosis by gram-negative bacteria; the most common bacterium isolated is Escherichia coli. Other organisms isolated include Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Clostridium perfringens and rarely Mycobacterium. EP is not uncommonly polymicrobial [4].

Radiologically contrast computed tomography (CT) is the modality of choice for imaging the pancreas and is highly sensitive and specific for detecting EP. CT will demonstrate gas bubbles within the parenchyma of the pancreas; this finding is not specific to EP, and differentials include patulous ampulla of Vater and duodeno-pancreatic fistula. Plain abdominal X-ray may demonstrate mottled gas overlying the mid-abdomen. Intravenous (IV) contrast is not essential to visualise gas; however it is useful in identifying associated necrosis [3, 4].

The standard of care for infected pancreatic necrosis is necrosectomy; however there is some evidence to suggest patients without end-organ dysfunction can be managed conservatively which may be particularly appropriate for poor operative candidates [1,5, 6].

We present a case of co-morbid elderly patient who developed EP and was successfully managed with conservative management of his pancreatitis with IV fluids, IV antibiotics and other standard cares.

CASE REPORT

An 87-year-old male presented to the emergency department with acute-onset vomiting and feeling generally unwell; he denied any localising features to suggest a cause including the absence of abdominal pain or features of infection. Clinically at presentation he was afebrile, mildly tachycardic and hypertensive. His abdomen was distended but soft and non-tender. Past medical history included type 2 diabetes and carotid artery stenosis.

Laboratory tests demonstrated a significantly elevated lipase of 1640 U/L and mildly deranged liver function tests (LFTs): alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 187 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 146 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 120 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 187 U/L and bilirubin 22/4 U/L (total/conjugated); he had a mildly elevated white cell count (WCC) of 12.6.

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated multiple gallstones including one lodged in the neck without evidence of cholecystitis and normal intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. At the time of this imaging, the pancreas was noted to be normal.

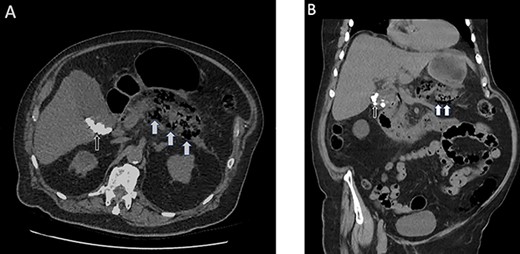

He was managed conservatively making minimal clinical progress and on day 3 developed a significant elevation of his inflammatory markers: C-reactive protein (CRP) >500, and WCC, 20. He had an associated acute kidney injury. His abdominal distension had increased with persistent vomiting. He progressed to have a non-contrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis that demonstrated extensive peripancreatic inflammatory change and interstitial air in the pancreas with associated air in the biliary tree and gallbladder as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

(A) Axial non-contrast CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis highlighting the interstitial air within the pancreas (white arrows) and multiple calcified gallstones within the gallbladder (black arrows). (B) Coronal view of the same scan.

The mainstay of management of pancreatic necrosis is necrosectomy; however given this gentleman’s multiple co-morbidities including diabetes, vascular disease and frailty, it was felt in his acutely unwell state that he would fare poorly from a general anaesthetic and major surgical debridement, being at high risk of cardiovascular events. His treatment was escalated however, and he was commenced on IV piperacillin/tazobactam with ongoing other routine conservative management for pancreatitis with IV fluids, parenteral feeding and nasogastric tube decompression of the stomach. Over the course of the following 48 hours, he had a downtrend of his inflammatory markers with his WCC falling to 14 and CRP to 246 and was improving clinically. He continued to improve and progressed to have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy on day 12 post presentation. At operation he was found to have an acutely inflamed gallbladder with a normal cholangiogram.

DISCUSSION

Emphysematous pancreatitis is a rare, severe and life-threatening complication of acute pancreatitis that is associated with a high mortality in excess of 50% [1, 2]. It most commonly occurs in morbid individuals particularly those that are immune supressed. Its presence is indicative of infective pancreatic necrosis that is usually associated with gram-negative infection, and it is not uncommonly polymicrobial [1, 3, 4].

The current standard of care of infected pancreatic necrosis is pancreatic necrosectomy [3, 5]; however there are a small body of evidence and case reports where it has been successfully managed conservatively. Conservative measures include organ support, pancreatic rest in conjunction with empirical broad-spectrum IV antibiotics covering the most common organisms or antibiotics based on positive cultures [1, 5, 6].

It is our experience in this case that EP can be managed successfully with these conservative measures. However for those patients failing to progress with conservative management, strong consideration needs to be given to escalation of therapy with either percutaneous drainage or surgical debridement [3]. As with all patients, there needs to be a balance of risk and benefit of any intervention. Pancreatic debridement involves extensive surgical mobilisation of other organs and then debridement of the pancreas. This degree of intervention is a major insult to the body and can result in worsening organ failure particularly in those with significant co-morbidities. It is therefore reasonable to trial conservative or less invasive interventions for those who are particularly high risk of operative intervention. These measures include commencing antibiotics for infected necrosis and percutaneous drainage of predominantly liquid collections.

Patients who would not be appropriate for conservative management are those with worsening organ dysfunction and deterioration despite maximum conservative measures; patients where there is concern for a coexisting pathology such as colonic ischaemia that would require surgical intervention; and those with predominantly solid or semisolid infected necrosis that would not be adequately drained with a percutaneous intervention and have deteriorated despite conservative measures [7].

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

FUNDING

None.