-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francesco Vito Mandarino, Giuliano Francesco Bonura, Dario Esposito, Riccardo Rosati, Paolo Parise, Lorella Fanti, A large anastomotic leakage after esophageal surgery treated with endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 4, April 2020, rjaa071, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa071

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The treatment of anastomotic post-esophagectomy leaks and fistula is challenging. Endoluminal vacuum-assisted closure (EVAC) is an emerging technique that employs negative pressure wound therapy to treat anastomotic leaks endoscopically. Esosponge is specifically designed for esophageal EVAC therapy. We report on a 49-year-old woman who underwent a totally mini-invasive Ivor–Lewis esophagectomy and developed a giant postoperative leak with a complex pleural collection, but she was not fit for surgical re-intervention. The patient healed almost completely after 14 exchange sessions of Esosponge over 35 days.

INTRODUCTION

Anastomotic leaks after surgery for esophageal cancer remain a potentially deadly complication whose therapeutic approach is still under debate.

The surgical approach to a post-surgical anastomotic leak is mandatory in case of mediastinitis or severe sepsis. However, the high mortality rate leads to consider alternative approaches.

EVAC is an emerging technique to treat anastomotic leaks endoscopically. Esosponge (Esosponge; Braun, Aescula AG, Tuttlingen, Germany) is a device specifically designed for esophageal EVAC therapy. The kit contains a polyurethane sponge placed on the tip of a drainage tube: this is pushed into the cavity or the lumen through its own overtube under endoscopic guidance. The drainage tube is diverted through the nose, and it is connected to a vacuum device with a continuous negative pressure of 75–100 mmHg. The sponge should be replaced every 2–3 days.

We present a successful case of Esosponge treatment for a giant anastomotic leakage.

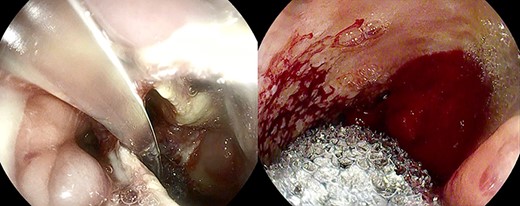

Large anastomotic leakage after minimally invasive esophagectomy opening to a cavity in the pleural space of 8 cm in size.

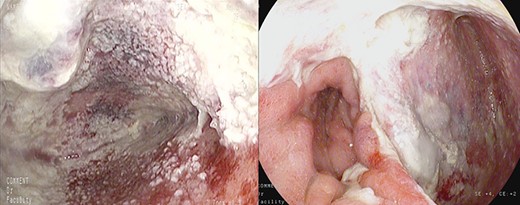

Healthy-appearing granulation tissue and progressive reduction of leak and cavity size.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old woman with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy, followed by a minimally invasive Ivor–Lewis esophagectomy.

On the third postoperative day (POD), inflammatory indexes increased (CRP 178.2 ng/mL). On the fourth POD, the endoscopy and CT scan showed a large anastomotic leak involving 75% of the anastomosis and opening to a giant wound cavity in the pleural space of 8 cm in size; fibrosis and abundant necrotic tissue were also present (Fig. 1).

Clinically, the patient presented with acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by sepsis requiring intensive care with ventilatory support and antibiotic therapy. Sepsis would normally urge surgical revision, but respiratory complications made the surgery extremely life-threatening.

Anastomotic dehiscence was conservatively treated by EVAC therapy, placing the Esosponge in pleural space via an overtube (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent 14 treatment sessions over 35 days. The leak and the cavity size progressively improved with the development of healthy-appearing granulation tissue s (Fig. 3). Inflammatory indexes and clinical conditions similarly improved. The endoscopic findings were confirmed by CT scans. Complications were not observed.

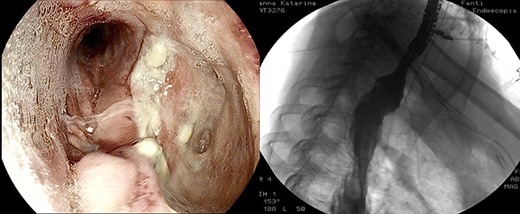

After the 14th session, the endoscopic evaluation showed a significantly cleaner and smaller cavity (1 cm). Two esophageal fully covered SEMS (Taewoong Niti-S Beta Stent) allowed the patient to have a liquid diet while the leak was safely healing: the stents were subsequently placed and kept for 3 weeks each. Endoscopy and esophagram were performed after SEMS removal, and they demonstrated leak resolution, with a tiny persistent depression at the site (Fig. 4). The patient has not had symptoms of recurrent fistula formation for over 6 months.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of post-esophagectomy anastomotic leaks is still challenging. The appropriate strategy is selected after evaluation of many factors including the size of anastomotic leakage, time since surgery and patient’s general conditions.

Medical conservative management (nihil per os, IV antibiotics), surgical correction and mini-invasive endoscopic procedures are available options to treat anastomotic leaks.

Surgical re-intervention is the standard of care and usually preferred in sepsis, even though no clear evidence supports the practice. However, in our case, the severe respiratory failure made the surgical option prohibitive. In this setting, EVAC and, eventually, the placement of an esophageal stent proved to be a better and safer therapeutic option than surgery [1].The placement of a SEMS is the most widespread endoscopic treatment, but guidelines do not address the matter of the type of device and timing for its removal. However, in our case, necrosis of anastomosis and the size of leakage posed a contraindication to the stent placement because of the risk of surgical site disruption, leak size increase, SEMS dislocation and exclusion of undrained infected cavity. Therefore, upfront endoscopic drainage was the only option.

EVAC uses the main principle of negative pressure wound therapy by decreasing bacterial contamination and local edema while promoting perfusion and granulation tissue formation. The sponge can be placed in either an intraluminal or an intracavitary position across an internal fistula opening, using the overtube with a designated pusher. In our case, the sponge was always set inside the cavity because of the large size of the collection.

The sponge is replaced with gentle traction of the tube in place, and a new one is repositioned. The sponge needs to be generously dampened with saline injected into the tube before the removal.

In early experiences with Esosponge, the time between sessions was about 1–2 weeks [2], while satisfactory results have been achieved with more frequent sponge changes (2–3 days) [3–5]. Initially, we changed the sponge every 2–3 days, and then we opted for 4–5 days intervals, because the local and general conditions of the patient were remarkably improving.

Small-case series reported success rates of EVAC in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal anastomotic leaks to range from 86 to 100%. In the largest prospective series by Laukoetter et al., sponges were changed every 3–5 days and were placed either intraluminal or into the cavity depending on the defect size with a success rate of 94%. In one patient, a SEMS was placed at the end of EVAC to complete the closure of the fistula as in our experience [6].

Kuehn et al. performed a systematic review on the use of EVAC in the management of upper gastrointestinal defects, including more than 200 patients. The authors reported an overall success rate of 90% (range 70–100%) with a duration of therapy ranging from 11 to 36 days [7].

A recent study showed that performing EVAC in the gastrointestinal lab provides a 2.5 reduction in total cost compared to surgical therapy [8].

In conclusion, in our case, EVAC has been a reliable, safe and effective treatment of post-surgical anastomotic leaks.

EVAC could be a promising option to improve the outcome of patients affected with large transmural leakages who would otherwise require surgery with its risks. Limitations are the costs of the device and the number of sessions needed (repeated sedation, procedure room time, scheduling difficulties). However, further prospective studies are required to confirm the findings of this single experience on larger cohorts of patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.