-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elroy P Weledji, Theophile C Nana, A fistulating incarcerated incisional hernia: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 4, April 2020, rjaa062, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa062

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

An incisional hernia is usually a defect in the scar of an abdominal surgery. The natural history is intestinal obstruction with the risk of strangulation. We report a case of a long-term conservative management of an incisional hernia with an abdominal corset. This resulted in fistulation from pressure necrosis that required an en-bloc excision of the incarcerated fistulating bowel with the hernia sac. The defect was managed using the Jenkin’s ‘mass closure’ technique with no recurrence of the hernia.

INTRODUCTION

An incisional (ventral) hernia is a bulge or protrusion that occurs near or directly along a prior abdominal surgical incision. It is as the result of the partial breakdown of the muscle layers with the epithelial layer intact (Fig. 1). This weakness around the wound scar is due to weakened fascia of the abdominal wall that may occur months after the operation. The incidence is about 8% [1] and the causes are (i) infection that may even be low grade and (ii) poor sutures e.g. absorbable (vicryl) used instead of non-absorbable (nylon) for abdominal wound closure [1, 2]. An incarcerated hernia is no longer reducible, but the vascular supply of the bowel is, however, not compromised. Bowel obstruction is common. These hernias often present with localized swelling and tenderness adjacent to the surgical scar, but their actual content and internal orifice are seldom palpable. Under these circumstances, evaluation of the abdominal wall by sonography or computed tomography can provide the correct diagnosis [3, 4].

![Schematic diagram of incisional hernia [2] (with permission).](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2020/4/10.1093_jscr_rjaa062/1/m_rjaa062f1.jpeg?Expires=1773798412&Signature=GpiHMHfLYVwsDfBUohEthWOKn8xECbpavs3Egb0BsEna8riTzNRnxibPHtCzj6chad~rz0XRPfhCdIIsVMKAbC103VvYg9rBQobpV3EdeJrtRr1WfGaiRiE-q~ZCky7n3oMhP7SXflHt4r8fcbi4Qb7r8Hyy-97nm-k5l0~UD8zjvrLCskAZFrpgLyRsLEkatiiFFOLBP~FOjoiZHcGlGXDNUgrJ0ezZwDhA1eNxNK20Zx1fRwVixWXwi9xHGFeJLkQq~-Sb17ALyo7BjGkc9Lmx98Zy6AXiatVINctapo3e~~4F0W-y6U9X5Mw3cyU5oFJyJKamjWvEl9QnSZ3A7Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

Incisional hernia through a low midline scar of previous surgical operation.

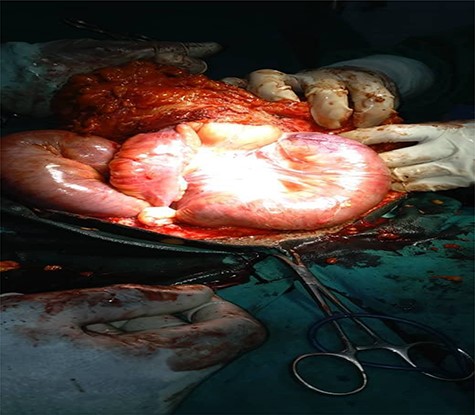

Opened hernia sac with incarcerated bowel loops and obstructed proximal small bowel.

![Schematic diagram of evisceration [2] (with permission).](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2020/4/10.1093_jscr_rjaa062/1/m_rjaa062f6.jpeg?Expires=1773798412&Signature=OqnS9rjGR1Z7~ycYAC4nP3cp10pUREhs8OzjgpLGO4-~y1eLLRaWePxCmEoqd4sZUOIuUvzkK9n1ilCWP3TQfHKMYDwTeTWA1yQUG~NGm2PLg-0D-DYQ0I23ZB-W7WG~hJ~38xevD4wcc5EFGJleOVl6prNacjlQFOkwwoyIieRn2IL7DuzP-tj~T0EttNSA~-EyzYEmamnodxeU5bg9XA5WV-iC2LYfzQGBBYH7N24FTl7DZ1D8tkCsiBkx51LF8Dk1kt3fEJFR1u---xqwAk4AagLVa4a5StBZ2iUDrhWG8Aubta8aAVAWclNkYke5d1cxmAqzWW25zIgB51YcpA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old African woman was admitted as an emergency with a 1-week history of progressive abdominal pain, vomiting and absolute constipation. These were associated with a large lower midline circumscribed abdominal swelling consistent with an incisional hernia. She had undergone a hysterectomy 12 years previously, which was complicated by a urinary fistula for which she underwent a laparotomy and repair. The incisional hernia developed a few years later and was managed conservatively with an abdominal corset and diet control. On examination, there was evidence of proximal small bowel obstruction secondary to a large, tender and irreducible incisional hernia with a fecal fistula at its apex (Fig. 2). The full blood count and serum biochemistry were within normal limits. Following resuscitation with i.v. fluids and nasogastric decompression, a difficult laparotomy through a wide re-opening of the old lower midline scar revealed grossly dilated small bowel loops incarcerated in an incisional hernia sac, which contained copious serous transudate (Fig. 3). Due to the technical difficulties in releasing the incarcerated small bowel, the hernia sac was excised en-bloc with the incarcerated and fistulating ileal loop. An ileo-ileal anastomosis between the viable bowel ends was made and the hernia defect repaired with the Jenkin’s mass closure suture technique. A non-absorbable 1-0 nylon suture on a round bodied needle was passed through all layers of abdominal wall except skin. A 4-1 suture to wound length ratio was used, and with big tissue bites (1 cm apart and 1 cm from edge of wound) producing a concertina, these would take any increase in tension without cutting out. A mesh repair technique with its lower failure rate could not be used in the infectious setting. The skin was closed with interrupted nylon suture to allow drainage. The operation took 4 hours. Post-operative recovery was complicated by a copious seroma for a week that led to a superficial wound dehiscence and a mild wound infection. This was managed conservatively with daily wound dressings and a 1-week therapeutic course of broad-spectrum i.v. cephalosporin (ceftriaxone) 1 g b.d. and metronidazole 500 mg b.d. for anaerobes. She was discharged 2 weeks after the hernia repair and continued with out-patient dressings to allow the wound to heal by second intention. At 3-month follow-up, the wound had almost completely healed and there was no evidence of recurrence of the hernia (Figs 4,5).

DISCUSSION

This case demonstrates the rare presentation of a fistulating incarcerated incisional hernia following a prolonged conservative management with an abdominal corset. Pressure necrosis may have caused the fistula as there was no vascular compromise of the bowel. Although the mesh repair of incisional hernia gives the best result, it could not be used in this setting with incipient fecal contamination. By providing minimal tension in the tissues and allowing fibrosis to occur naturally in the interlacing network of a mesh recurrence is minimized [5]. However, the layer of the abdominal wall in which the mesh is placed (onlay or sublay) is an important factor [5–7]. Laparoscopic hernia repair as a bridged repair in which mesh spans the unclosed fascial defect of the hernia would result in poor function of the abdominal wall [8]. A potential solution is primary fascial closure prior to mesh placement [8]. Apart from decrease surgical site infection and length of hospital stay, there is no difference in hernia recurrence between laparoscopic or open repair [6–8]. Thus, less than a quarter of ventral hernias are repaired using the laparoscopic technique [8]. The suture repair technique is known to have a high-failure rate if primary fascial closure is not done [1, 8]. Primary fascia closure restores the linea alba (anterior and posterior rectus sheath), realigns the rectus muscles and places the abdominal wall muscles under the physiological tension needed for optimal function [8]. The success of the suture repair in this case was due to the author’s use of the Jenkin’s ‘mass closure’ technique with a continuous non-absorbable 1-0 nylon suture of a 4-1 suture wound length ratio and in taking big bites of the fascia. This creates minimal tension in the deep tissues as the big bites produce a concertina and a suture that is considerably longer than the wound. There is a smaller rise in tissue tension when the wound is stretched in the early post-operative period, when the patient coughs or is distended [2, 9]. The ‘mass closure’ technique will also allow a ‘cement’ nature of healing similar to mesh. This would be the reverse with the increased tension generated from several interrupted sutures required otherwise to bring the defect together and enable closure of the abdominal wall. Similarly, the Jenkin’s mass closure technique is known to be more efficacious than the tension sutures advocated by some authors for the ‘burst abdomen’—a complete wound dehiscence with an open epithelial layer resulting in evisceration (Fig. 6) [9]. Seroma formation remains a common complication after an incisional hernia repair, but the authors took no measure to reduce seroma formation perioperatively [10].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the theatre and surgical nursing staff of the Regional Hospital Limbe for the perioperative care of the patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.P.W. was the main author and surgeon; T.C.N. contributed to literature search.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.