-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hong Lee, Saman Shafiezadeh, Rajeev Singh, Fumarase-deficient uterine leiomyoma: a case of a rare entity and surgical innovation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 3, March 2020, rjaa044, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa044

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report a case of a 47-year-old female, with strong preoperative clinical and radiological suspicious of uterine leiomyosarcoma who underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy. Despite the final histology concluded as benign uterine leiomyoma, the loss of fumarate hydratase expression of the same specimen still put her at risk of having hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome. Intraoperatively, an obstetric vacuum cup was used for uterine manipulation to avoid breaching of the uterine serosa.

INTRODUCTION

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) is an autosomal-dominant syndrome caused by fumarate hydratase gene mutation. The patients may develop benign uterine leiomyoma, uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS) and type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. Inadvertent disruption of occult uterine LMS during gynecological procedures like hysterectomy or myomectomy may result in peritoneal seeding and consequently subject patients to unnecessary adjuvant treatment. We report a case of a 47-year-old female, with strong preoperative clinical and radiological suspicious of uterine LMS who underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy. Despite the final histology concluded as benign uterine leiomyoma, the loss of fumarate hydratase expression of the same specimen still put her at risk of having HLRCC syndrome. Intraoperatively, an obstetric vacuum device was used for uterine exteriorization and manipulation.

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old Caucasian female presented with a history of new onset stress and urge urinary incontinence, a sense of rectal pressure and incomplete bowel emptying. It was worsening rapidly over a period of 6 months and highly impacted her quality of life. She was otherwise healthy, with normal body mass index and no significant past medical history. She denies any abnormal uterine bleeding. On abdominal examination, a firm mass was palpable at the level of umbilicus. On bimanual examination of the pelvis, an 11-cm pelvic mass was palpated at the upper posterior vagina totally pressing on the mid rectum occupying the pouch of Douglas.

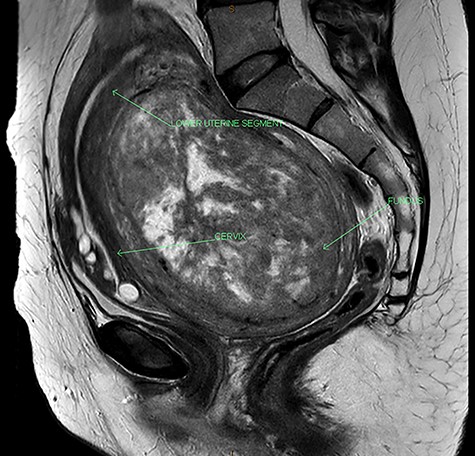

Her pelvic ultrasound showed a large posterior intramural leiomyoma, 112 × 72 × 89 mm, distending the uterus posteriorly and does not breach the subserosa surface. The endometrium has a normal contour. In view of the rapid onset and worsening of her symptoms, a pelvic MRI was performed to further characterize the uterine lesion, also to detect any regional lymphadenopathy. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a very large uterine fundal leiomyoma measuring 13 × 10.3 × 7.6 cm, displacing and distorting the other uterine structures in the setting of a retroflexed and retroverted uterus (Fig. 1). There is elongation of the lower uterine segment. The cervix is displaced anteriorly, while the bladder and bowel are compressed. No evidence of parametrical infiltration or regional lymphadenopathy was seen.

MRI of the pelvis showing acutely retroflexed uterus with the fundus occupying the pouch of Douglas.

She underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy with ovarian conservation. A Kiwi® OmniCup (Fig. 2) was used instead of sharp instruments (i.e. Kocher forceps or myomectomy screw) for uterine manipulation, mainly to avoid breaching of the uterine serosa that could potentially cause seeding of the leiomyosarcomatous tissue (Fig. 3). The peritoneal washing was negative for malignancy. The histopathology ruled out LMS but revealed leiomyomata with the dominant leiomyoma showing a loss of fumarate hydratase expression.

Intraoperative placement of Kiwi® OmniCup on the uterine fundus for ease of uterine manipulation.

DISCUSSION

HLRCC is a genetic condition that has affected approximately 200–300 families worldwide [1]. The main clinical manifestations of HLRCC are as follows: cutaneous piloleiomyomas, renal cell cancer and uterine leiomyoma. Cutaneous piloleiomyomas may appear as papules distributed over the trunk and extremities cutaneous in 80–100% of the patients. The lifetime renal cancer risk in HLRCC is 15%, with type 2 papillary renal cell cancer being the most common type [2, 3]. Once proven to have carried the genetic mutation, lifelong renal cancer surveillance with annual MRI is recommended [4].

Female HLRCC patients tend to have surgical procedures like myomectomy and hysterectomy performed earlier than general population due to the early development of the uterine disease. LMS, being an aggressive uterine tumor, still remains a rare but possible manifestation of HLRCC. The incidence of LMS being found in hysterectomy specimen presumed to be benign uterine leiomyoma is 0.5% [5].

Preoperative diagnosis of LMS remains a challenge, as clinical features of LMS and benign leiomyomas are often indistinguishable on ultrasonography [6]. On MRI, typical uterine leiomyomas present as well-delineated masses of variable size that may be solitary or multifocal while LMS usually appears as poorly demarcated masses with irregular and ill-defined border, often nodular and with invasion of adjacent structures [7, 8].

The delivery of a large pelvic mass through a surgical incision may be difficult and equally frustrating. Exteriorization and manipulation of the mass may be quite cumbersome. Unexpected tearing and damage to surrounding tissues and to the mass itself can result in marked blood loss. An appropriate preoperative workup permits a near accurate evaluation of the mass [9].

As part of preoperative planning and surgical innovation, the Kiwi® OmniCup, a small, economical, readily available and flexible plastic device commonly used for assisted vaginal delivery, was used from the exteriorization of the enlarged uterus up until colpotomy was performed. As the uterus of our patient was retroverted and acutely retroflexed, the uterine fundus was wedged deep down in the pouch of Douglas. The Kiwi® OmniCup was initially slide in and positioned at the high anterior serosa of the uterus and was easily exteriorized without concerns of surrounding tissue damage. The cup was then replaced to the desired position of the uterus to be manipulated in order to optimize the surgical exposure for a safe and efficient hysterectomy. The suction pressure of the cup can be easily and dynamically be adjusted with the hand piece between 0.2 and 0.8 kg/cm2. This feature allows optimal effect with the minimum suction pressure required efficiently. Consequently, the risk of inadvertent breaching of the surface of the mass by unnecessarily high suction pressure is minimized, resulting in minimal surgical blood loss and preventing intra-abdominal dissemination of potentially malignant intrauterine tissue [10]. In the literature, there has not been case report describing the usage of obstetric vacuum devices causing detrimental effect on patients with leiomyosarcoma when it was applied on the uterine serosa surfaces.

This case highlights the importance of having awareness of rare clinical conditions in the context of very common gynecological presentations—uterine leiomyoma and stress urinary incontinence. Measures were taken carefully from radiological diagnosis, preoperative planning and intraoperative surgical steps in order to optimize the best outcome for our patient. Postoperatively, despite being concluded to have a benign histology, our patient and her family were still at risk of developing aggressive renal cancer and were potentially subjected to lifelong surveillance.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.