-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nina Kabelitz, Berit Brinken, Rudolf Bumm, Retroperitoneal perforation of a duodenal diverticulum containing a large enterolith after Roux-en-Y bypass and cholecystectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 2, February 2020, rjz383, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz383

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most frequently performed bariatric procedures worldwide. The postoperative incidence of cholelithiasis after RYGB is higher than in the general population (30% vs. 2–5%), because the altered anatomy may lead to impaired gallbladder motility and biliary stasis. We report the case of a 47-year-old female who presented 9 years after RYGB and cholecystectomy with acute pain in the upper abdomen because of a retroperitoneal perforation of a duodenal diverticulum. Intraoperatively, a huge enterolith was found in the diverticulum and removed via duodenotomy. We claim that the stone grew during the sober states as the bile accumulated locally, because the gall bladder has already been removed and no duodenal food passage remained. This acute and life-threatening situation was successfully managed by operation. Consequently, a duodenal diverticulum has to be considered as a possible but very rare complication after RYGB and cholecystectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most frequently performed bariatric procedures worldwide [1]. Small-bowel obstruction (SBO) after RYGB is a common complication (mostly due to adhesions or internal herniation) but seldom generated by bile duct stones (BDS) [2]. The postoperative incidence of cholelithiasis after RYGB is higher than in the general population (30% vs. 2–5%), because the altered anatomy may lead to impaired gallbladder motility and biliary stasis [3]. The latter has also been described in intestinal diverticula, which mostly occur around the duodenal ampulla of Vater (periampullary diverticula (PAD)). The incidence for CBD stones after previous cholecystectomy is reported between 3% and 24% [4]. Consequently, if a periampullary diverticulum exists, cholecystectomy does not prevent from the occurrence of (CBD) stones [5]. Mostly, the formation of BDS after cholecystectomy is clinically insignificant. However, in rare cases, BDS passage, penetration or enterolith formation may lead to acute clinical symptoms. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography is often not suitable for treatment after RYGB [1, 6, 7] and surgical intervention is needed. We describe a rare case of a perforated duodenal diverticulum after RYGB caused by an enterolith.

CASE REPORT

Patient history

A 47-year-old female (body mass index, 30.5 kg/m2 (160 cm, 78 kg)) presented in a corresponding hospital with acute pain in the upper abdomen after gastric bypass and cholecystectomy 9 years earlier and loosing 40 kg weight afterward. At the first consultation in the emergency department, she complained of massive abdominal pain since the night before admission, which did not respond to analgesic drugs. Because of the patient’s history of bariatric surgery and the suspicion of SBO, a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which was inconclusive at the first look with multiple differential diagnoses. It showed a thickening of the wall of the ascending colon and a diverticulum of the duodenum with semisolid contents. The patient was then referred to our hospital for further treatment.

Status and findings

In our emergency department, the patient’s general condition was reduced because of pain and signs of diffuse peritonitis. The vital signs showed a blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg and an accelerated pulse (120 bpm), a respiratory rate of 25/min and a normal body temperature. The blood results showed a leukocytosis with only slightly elevated C-reactive protein (14 mg/l). The CT scan was reviewed and revealed the presence of retroperitoneal and parapancreatic fluid with some air bubbles, which could also be seen in an additional abdominal sonography. Further a thickening of the colon ascendens was found (Fig. 1). A perforated duodenal diverticulum was likely and suspected. The thickening of the ascending colon was interpreted as an accompanying colitis.

Therapy

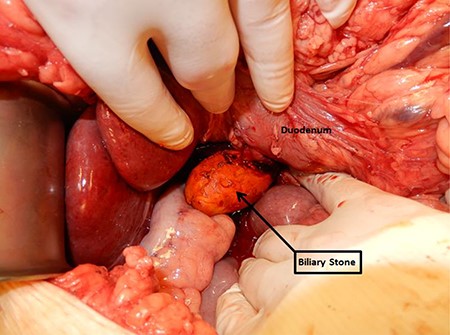

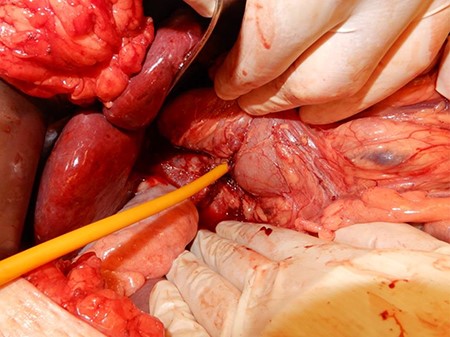

Attributable to the reduced condition of the patient with little response to opioids, signs of diffuse peritonitis and our interpretation of the imaging, we decided to perform an explorative transverse laparotomy in the upper abdomen. Although the right colic flexure was mobilized, the exposure of the duodenum was difficult and very limited. However, a hard resistance could be palpated. After a Kocher maneuver and exposing the duodenum and the pancreas dorsally, we were then able to dissect the duodenal diverticulum. The diverticular wall was incised and a biliary stone of the size of ~7 × 4cm was exposed and removed (Fig. 2). Sutures then reattached the duodenal wall. A T-drain was placed intraduodenally, an Easy-Flow drain paraduodenally (Figs 3 and 4). Postoperatively, the patient was admitted to the ICU for initial surveillance. An empiric intravenous antibiotic therapy with Piperacillin/Tazobactam was initiated. After one night, the patient could be transferred to the normal ward in stable condition.

Follow-up

The postoperative course was uneventful. Pain was controlled with basis analgesia and slowly she returned to a normal diet. Inflammatory markers were declining and antibiotics could soon be stopped. Ten days postoperatively, a fistulography showed a persistent retroperitoneal collection of 3 × 3 cm so the drains were left in situ. Two days later, the patient was discharged from the hospital in proper general condition but with extraduodenal drains still in place.

One week after dismissal, the patient felt well with normal appetite and a regular intestinal passage. The fistulography showed a significant reduction of the collection so the T-drain was removed. Two weeks later, she still felt irritated by the last remaining Easy-Flow drainage, which continued showing some turbid liquid and was therefore left in situ. Intestinal passage was unchanged and there were no signs of inflammation. Another 2 weeks later, the drain fell out by accident. Seven weeks postoperatively, still no signs of inflammation, we were able to finish our treatment.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In current literature, enteroliths and bile duct stones are associated with PAD and are seen more often after bariatric surgery. The mechanisms leading to this cause are not fully understood yet. Our patient presented following two risk factors: a duodenal diverticulum and a status after RYGB surgery; both sources of stasis that may lead to development of stones. Furthermore, obesity and rapid changes of weight (e.g. after bariatric surgery) are also associated with a higher incidence of cholelithiasis [7]. In the presented case, the duodenal diverticulum was not periampullary but originating from the pars horizontalis of the duodenum. For that, we claim that the stone grew during the sober states as the bile and bile salts accumulated in the diverticulum, because the gall bladder has already been removed and no duodenal food passage remained. We managed this acute clinical situation via an open surgical approach because of the difficult anatomic situation and patients’ history of previous abdominal surgery. Although symptomatic enterolithiasis is a very rare complication after RYGB, the threshold for surgery should be low if clinically suspected.

Most important points for daily practice

Bariatric surgery presents a risk factor for developing bile duct stones even after cholecystectomy, because the altered anatomy may lead to stasis

Cholecystectomy does not prevent from the occurrence of bile duct stones if diverticula exist

Threshold for surgical intervention should be low if complications after bariatric surgery are clinically suspected

Operative stone removal and elimination of the underlying cause seems to be the first choice, if bile duct stones lead to complications

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

References

Author notes

Nina Kabelitz and Berit Brinken have shared first authorship in the article.