-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lova Hasina Rajaonarison Ny Ony Narindra, Vatosoa Sarobidy Nirinaharimanitra, Francis Allen Hunald, Ahmad Ahmad, Two new cases of pediatric tumoral calcinosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 12, December 2020, rjaa481, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa481

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Tumoral calcinosis (TC) is a rare benign pathology, particularly in pediatrics. It is difficult to diagnose with its pathophysiology poorly understood. We report two pediatric cases of TC having benefited from radiological assessments and surgical excision. Final diagnosis was made by pathological examination. For the two cases, no sign of recurrence was noted ~30 months of follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Tumoral calcinosis (TC) is characterized by a deposit of calcium phosphate crystals in the extra-articular soft tissues, which are rare benign conditions, especially in children [1]. Apart from esthetic problems, these lesions are disabling by the importance of the tumor volume and the associated algic symptoms, thus requiring surgical resection. We report two female pediatric cases of TC for which one was multifocal and both caused major esthetic but also mechanical disturbances to describe their management. Medical imaging guided the diagnosis, which was secondarily confirmed by pathological examination of the excision pieces.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

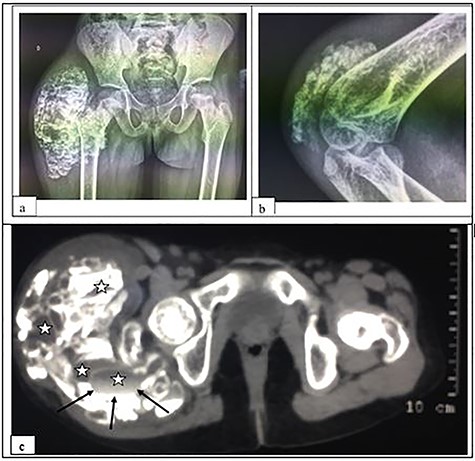

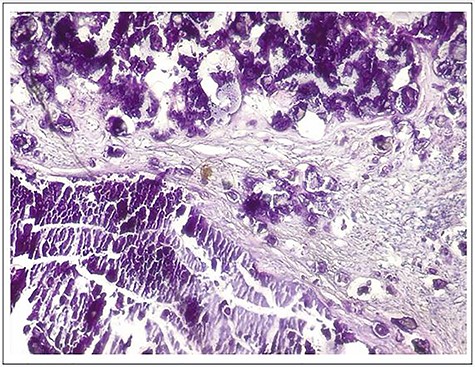

A 6-year-old girl was admitted for a hard and painless swelling of the right gluteal region and the right elbow. She had no particular medical or family history, particularly of any tumor or renal dysfunction. There were no particular functional signs apart from the mechanical discomfort caused by the swelling. Examination of the lower limbs and skin at the swelling were normal but extension of the right elbow was limited. Blood tests did not reveal anything in particular (calcemia, phosphoremia, alkaline phosphatase and parathormone were normal, there was no inflammatory sign and kidney function was normal too). Pelvis plain radiographs and right elbow showed calcified masses of extra-articular projection (Fig. 1a and b) without any joint or bone lesion abnormality. Right gluteal mass benefited from computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed a polylobed and extra-articular calcified lesion without joint or bone abnormality but it contained liquid components with liquid–liquid levels (Fig. 1c). This gluteal mass was resected due to mechanical and esthetic complaints, appearing hard and whitish peroperatively. Pathological examination revealed a cystic subcutaneous lesion consisting of central granular or amorphous material, calcified, surrounded by a macrophage reaction with multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear inflammatory elements; associated with numerous osteoid deposits scattered in amorphous layers with surrounding non-inflammatory fibrous tissue, related to TC (Fig. 2). Evolution was favorable with no sign of recurrence at 30 months of quarterly clinical follow-up for the gluteal lesion while the elbow lesion left in place did not evolve in terms of volume.

X-ray of the pelvis in frontal view (a) and of the right elbow in profile (b); and CT-scan without contrast media of the pelvis in soft tissue window (c), showing a calcified, multi-lobed mass containing fluid components (asterisk) with liquid–liquid level (arrows) in the extra-articular soft tissues. Note: the absence of joint or bone lesion detected.

Microphotograph of the specimen hematoxylin and eosin (H–E stain, ×10) showing cystic lesion consisting of central granular or amorphous material, calcified, surrounded by a macrophage reaction with multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear inflammatory elements; associated with numerous osteoid deposits scattered in amorphous layers with surrounding non-inflammatory fibrous tissue.

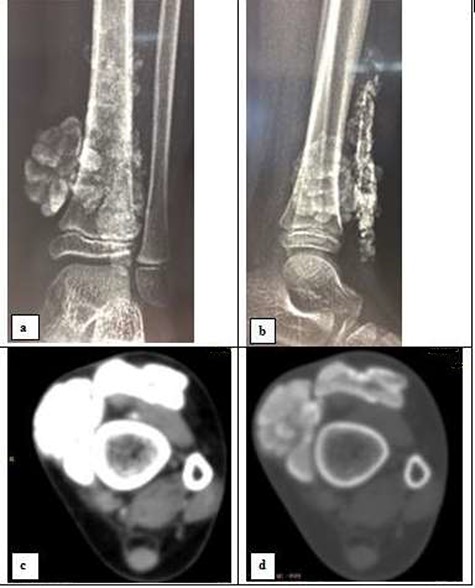

Radiography in frontal view (a) and profile (b); and CT-scan in soft tissue window (c) and bone window (d) of the left ankle showing a calcified polylobed mass in the extra-articular soft tissues and the lower third of the leg.

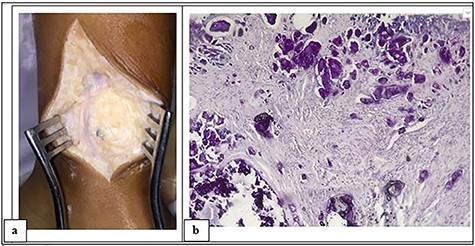

Intraoperative photograph of the mass showing a whitish appearance (a) and microphotograph revealing calcified amorphous material, surrounded by a macrophage reaction with multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear inflammatory elements; associated with numerous osteoid deposits scattered in amorphous layers with surrounding non-inflammatory fibrous tissue (H–E stain, ~10).

Characteristics of 18 TC reported in pediatric populations and its management

| Reference . | Ages . | Sex . | Localizations . | Dimensions . | Symptoms . | PNP . | PHP . | Secondary . | Treatments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 17 years (followed since 7 years) | F | Left hip, both elbow | - | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [4] | 6 weeks | M | Right hand | 5 cm | Swelling | no | Yes | – | Resection |

| [5] | 9 years | M | Right elbow | 4 cm | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [6] | 18 days/6 years | M/− | Sternum/right elbow | 3 cm/5 cm | Swelling/painful | – | Yes | – | Resection/resection |

| [9] | 15 years | F | Left hip | 15 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [10] | 8 years/12 years | M/M | Left subscapulary/both hip | 14.5 cm/8.5 cm | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [11] | 13 years | M | Thoracic spine | 3.1 cm | Swelling, painful, scoliosis | No | Yes | – | Embolization then resection |

| [12] | 18 years (followed since 10 years) | M | Left hip, right shoulder, left foot | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Paliative surgery, NSAIDs, aluminum hydroxide, phosphor depletion |

| [13] | 14 years | F | Both hip | 5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [14] | 10 years | M | Both hip | 6 cm | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Not treated (lost sight of) |

| [15] | 8 years | F | left elbow, both foot | 8 cm | Swelling, ulceration | Yes | No | – | Resection for symptomatic lesion |

| [16] | 2 months | F | Scalp, right hip | – | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Phosphate binder, acetazolamide |

| [17] | 16 months | F | Left subscapulary | 7.5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [18] | 13 years | M | Maxillary, both hip, left elbow | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [19] | 10 years/9 years | F/F | Both elbow | 6 cm/− | Swelling, painful, motion limitation, fistulization | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| Reference . | Ages . | Sex . | Localizations . | Dimensions . | Symptoms . | PNP . | PHP . | Secondary . | Treatments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 17 years (followed since 7 years) | F | Left hip, both elbow | - | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [4] | 6 weeks | M | Right hand | 5 cm | Swelling | no | Yes | – | Resection |

| [5] | 9 years | M | Right elbow | 4 cm | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [6] | 18 days/6 years | M/− | Sternum/right elbow | 3 cm/5 cm | Swelling/painful | – | Yes | – | Resection/resection |

| [9] | 15 years | F | Left hip | 15 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [10] | 8 years/12 years | M/M | Left subscapulary/both hip | 14.5 cm/8.5 cm | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [11] | 13 years | M | Thoracic spine | 3.1 cm | Swelling, painful, scoliosis | No | Yes | – | Embolization then resection |

| [12] | 18 years (followed since 10 years) | M | Left hip, right shoulder, left foot | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Paliative surgery, NSAIDs, aluminum hydroxide, phosphor depletion |

| [13] | 14 years | F | Both hip | 5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [14] | 10 years | M | Both hip | 6 cm | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Not treated (lost sight of) |

| [15] | 8 years | F | left elbow, both foot | 8 cm | Swelling, ulceration | Yes | No | – | Resection for symptomatic lesion |

| [16] | 2 months | F | Scalp, right hip | – | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Phosphate binder, acetazolamide |

| [17] | 16 months | F | Left subscapulary | 7.5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [18] | 13 years | M | Maxillary, both hip, left elbow | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [19] | 10 years/9 years | F/F | Both elbow | 6 cm/− | Swelling, painful, motion limitation, fistulization | No | Yes | – | Resection |

Characteristics of 18 TC reported in pediatric populations and its management

| Reference . | Ages . | Sex . | Localizations . | Dimensions . | Symptoms . | PNP . | PHP . | Secondary . | Treatments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 17 years (followed since 7 years) | F | Left hip, both elbow | - | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [4] | 6 weeks | M | Right hand | 5 cm | Swelling | no | Yes | – | Resection |

| [5] | 9 years | M | Right elbow | 4 cm | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [6] | 18 days/6 years | M/− | Sternum/right elbow | 3 cm/5 cm | Swelling/painful | – | Yes | – | Resection/resection |

| [9] | 15 years | F | Left hip | 15 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [10] | 8 years/12 years | M/M | Left subscapulary/both hip | 14.5 cm/8.5 cm | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [11] | 13 years | M | Thoracic spine | 3.1 cm | Swelling, painful, scoliosis | No | Yes | – | Embolization then resection |

| [12] | 18 years (followed since 10 years) | M | Left hip, right shoulder, left foot | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Paliative surgery, NSAIDs, aluminum hydroxide, phosphor depletion |

| [13] | 14 years | F | Both hip | 5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [14] | 10 years | M | Both hip | 6 cm | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Not treated (lost sight of) |

| [15] | 8 years | F | left elbow, both foot | 8 cm | Swelling, ulceration | Yes | No | – | Resection for symptomatic lesion |

| [16] | 2 months | F | Scalp, right hip | – | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Phosphate binder, acetazolamide |

| [17] | 16 months | F | Left subscapulary | 7.5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [18] | 13 years | M | Maxillary, both hip, left elbow | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [19] | 10 years/9 years | F/F | Both elbow | 6 cm/− | Swelling, painful, motion limitation, fistulization | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| Reference . | Ages . | Sex . | Localizations . | Dimensions . | Symptoms . | PNP . | PHP . | Secondary . | Treatments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 17 years (followed since 7 years) | F | Left hip, both elbow | - | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [4] | 6 weeks | M | Right hand | 5 cm | Swelling | no | Yes | – | Resection |

| [5] | 9 years | M | Right elbow | 4 cm | Swelling, painful | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [6] | 18 days/6 years | M/− | Sternum/right elbow | 3 cm/5 cm | Swelling/painful | – | Yes | – | Resection/resection |

| [9] | 15 years | F | Left hip | 15 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [10] | 8 years/12 years | M/M | Left subscapulary/both hip | 14.5 cm/8.5 cm | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [11] | 13 years | M | Thoracic spine | 3.1 cm | Swelling, painful, scoliosis | No | Yes | – | Embolization then resection |

| [12] | 18 years (followed since 10 years) | M | Left hip, right shoulder, left foot | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Paliative surgery, NSAIDs, aluminum hydroxide, phosphor depletion |

| [13] | 14 years | F | Both hip | 5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [14] | 10 years | M | Both hip | 6 cm | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Not treated (lost sight of) |

| [15] | 8 years | F | left elbow, both foot | 8 cm | Swelling, ulceration | Yes | No | – | Resection for symptomatic lesion |

| [16] | 2 months | F | Scalp, right hip | – | Swelling | No | Yes | – | Phosphate binder, acetazolamide |

| [17] | 16 months | F | Left subscapulary | 7.5 cm | Swelling | Yes | No | – | Resection |

| [18] | 13 years | M | Maxillary, both hip, left elbow | – | Swelling, painful, motion limitation | No | Yes | – | Resection |

| [19] | 10 years/9 years | F/F | Both elbow | 6 cm/− | Swelling, painful, motion limitation, fistulization | No | Yes | – | Resection |

Case 2

An 8-year-old girl was admitted with a swelling of the left ankle extended to the middle third of the leg evolving for >6 months, without any medical or family history of note. The swelling was hard and fixed, painless and did not affect walking. There were no local inflammatory signs or deterioration of the general condition. Calcemia, phosphoremia, alkaline phosphatase and parathormone were normal like creatinine and urea.

Plain radiograph showed a calcified, multi-lobed mass in the extra-articular projection of the ankle and lower third of the leg (Fig. 3a and b). Absence of joint or bone abnormality was confirmed on CT scan (Fig. 3c and d). Surgical management was chosen due to the esthetic complaints linked to tumoral location at the ankle, revealed a whitish mass with hard and muddy appearance (Fig. 4a). Pathology examination revealed calcified amorphous material, surrounded by a macrophage reaction with multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear inflammatory elements; associated with numerous osteoid deposits scattered in amorphous layers with surrounding non-inflammatory fibrous tissue (Fig. 4b). The evolution was favorable with no sign of recurrence after 24 months of quarterly clinical follow-up.

DISCUSSION

TC is a benign condition characterized by a deposit of calcium material in the extra-articular soft tissues [1, 2]. It is rare with ~300 cases reported, in which ~100 are familial and ~30 are pediatrics [1, 3, 4, 5]. TC are asymptomatic and especially painless unless they reach certain size to cause nerve or vascular compression or if they are in a particular location such as spinal [3, 5]. Swelling is hard and fixed in relation to the deep plane.

TC is difficult to diagnose, hence the multiplicity of its name in the literature [4]. Smack et al. [2] proposed a classification based on the pathogenesis of these TC through the review of 122 published cases. Thus, three subgroups of TC were established: primitive normophosphatemic (PNP) and hyperphosphatemic (PHP) and secondary TC. Familial involvement was noted in the PHP form and in the secondary form. These three forms can be encountered in the pediatric population. Our two cases are primitive normophosphatemic.

The average age of PNP-form patients is 22 years, 14 years for the PHP form and 24 years for the secondary form [2], even though Polykandriotis [4] described a neonatal form in an 8 weeks old boy in whom hyperphosphatemia was noted in the first week of life but it had been normalized 5 months later [4].

Despite the research published by Smack et al. [2], the physiopathology of TC remains controversial, even if the team of Slavin [6] has raised the possibility of a process of repairing a metabolic phospho-calcic disorder, which could be exaggerated by episodes of bleeding, and therefore raises the possibility of repeated trauma [3, 7]. Thus, TC is frequently localized in the extra-articular soft tissues of the hip, posterior region of the elbow or shoulder, foot and knee [1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9]. Other localizations are rare including ankle or leg like one of our cases mentioned above. TC secondary form is linked to chronic renal failure, primary hyperparathyroidism, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, hypervitaminosis D, massive osteolysis and other systemic pathologies [2, 3, 10].

TC mainly affects Black African and Latin American populations [2, 3, 9, 10]. This condition has no gender predilection [2]. In general, TC is unique but there are possibilities that it can be multiple as one of our series, and it can be bilateral as well [3, 10].

Spontaneous growth is generally slow, about several years [3, 10], contrasting with the neonatal case of rapid evolution described by Polykandriotis et al. [4]. Biology depends on the type of TC. Phosphatemia and calcitriolemia are elevated for secondary TC and the PHP form, and are accompanied by an increase in renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate, which will be less for the PNP form [2]. In the majority of cases serum calcium, calciuria, phosphaturia and alkaline phosphatase are normal.

Imaging is essential to diagnose TC. Ultrasound shows a calcified mass with posterior shadowing and containing echogenic components with liquid–liquid level, without Doppler flow [1, 10]. On X-ray, TC corresponds to a multi-lobed mass of extra-articular projection without damage of bone structures and articular surfaces. Each lobulation is well limited and separated from septas of variable density according to calcium components [10]. CT scan allows a good description of TC as a multicystic mass with thin septas of variable density and containing sediments with characteristic liquid–liquid levels [1]. If MRI is performed, TC presents as a heterogeneous signal mass on T1 and T2 weighted images [5, 10]. Fibrous septas separating the lobules are of low signal on T1 and T2 weighted images while the content of the lobules and the perilobular structures are high signal on T2. T2 weighted images reveal the liquid–liquid level realizing the sedimentation sign.

Management of TC depends on its type, size, relations and symptoms [3]. Two types of treatment are available. For PNP and PHP, the first-line treatment is radical surgery. Recurrence can occur even in the long term [2]. Table 1 summarizes the major caracteristics of TC reported in peadiatric populations and its managment. Medical treament must be adopted for secondary form with hyperphosphoremia and consists in fixing the phosphocalcic disorders. However, no malignant transformation has been reported so far.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.